With the 2020 presidential election, we, the people, succeeded in enacting our political will. This article is about the nitty-gritty of participatory democracy, how we, ordinary citizens, kept our feet on the ground and our eyes on the prize in the middle of a pandemic, sustaining the voting process. Meanwhile, our opponents broke one democratic norm after another, denied that Biden had won the election, and mounted a violent insurrection against our constitution and the rule of law.

As Biden, standing on the very platform that had been swarmed over by the enemies of democracy two weeks before, said on January 20, 2021 in his inauguration speech:

“Today, we celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause, the cause of democracy. The will of the people has been heard and the will of the people has been heeded. We have learned again that democracy is precious. Democracy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed.”

Words and sentiments he repeated later that day at the Lincoln Memorial:

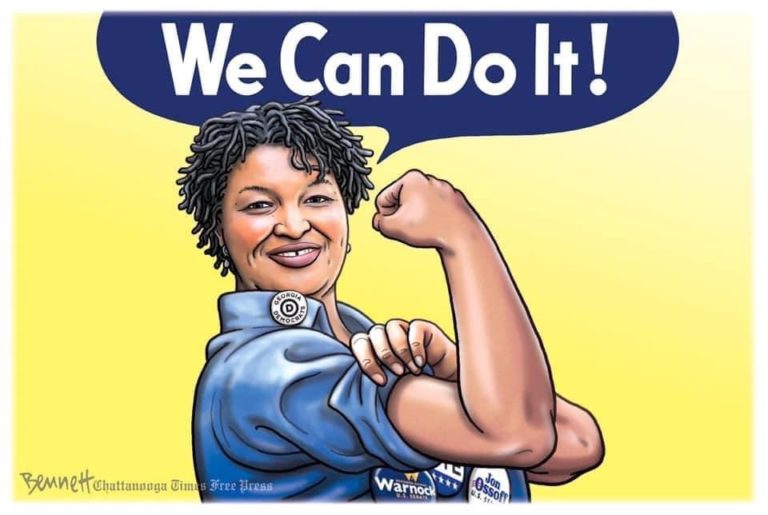

Here I want to share with you how we won the election for Biden, what our click campaign was all about and how it worked, breaking with the way the voting process was supported in the past. I’ll delve into other matters too that contributed to the win, what Stacy Abrams, Georgia State Representative and Democratic leader, did to create a level playing field for elections in Southern states and how the Progressives organized against sabotage.

The Click Campaign: Going Online to Support the Voting Process

Every campaign I have joined has involved working out of a candidate’s field office where we conducted telephone banks, licked envelopes and pored over constituency lists while teams were dispatched to go door to door in our neighborhoods, discussing with anyone who would listen why they should vote for our candidate.

In every case, there was a lot of foot leather expended, and considerable camaraderie around tables groaning with snacks and pizzas and gallons of pop and coffee (the Obama field offices served the best nosh ever).

This year was different. Although some of my friends mailed out handwritten postcards and others walked the neighborhoods “door-knobbing” – fixing campaign flyers to doors but not engaging in conversation – online campaigning proved our most effective tactic. As Charlotte Alter puts it in “The Click Campaign: Inside Joe Biden’s Uphill Battle to Win the Internet”:

“For more than half a century, Democrats have put their faith in field organizing as the key to campaign success. But this year, instead of marching through neighborhoods with clipboards, Democratic staffers, campaign volunteers and activists across the party are texting, messaging and commenting on their neighbor’s virtual doorsteps.”

Writing in August 2020, Alter was not at all sure that the “Click Campaign” would get Biden elected. It did.

She gives the example of online activist Mariana Castro, a 26 years old from Peru who was protected from deportation by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and who has spent most of her adult life advocating for immigrants’ rights:

“Now, as the deputy digital director for the Florida Democratic party, Castro helps lead a team of 6 women, all in their 20s, who spend their days organizing Florida voters on social media. They live in five different cities–one in New York–and none have ever met one another, but they’ve become a close-knit team through daily Google Hangouts and FaceTime calls. Not even Castro and her boss, Chelsea Daley, 26, have met in real life.”

Not meeting in real life hasn’t prevented them from optimal strategizing to get their message on as many digital platforms as possible, adjusting to the ways different audiences communicate on each platform.

On Twitter and TikTok, Facebook, Pinterest, and Instagram, they devised all kinds of creative, innovative, and generation-appealing memes to get out the vote.

In addition to campaign sites set up online by the Biden/Harris campaign, a variety of organizations established platforms to phone or text from home.

Rock the Vote, for example, used “rational voting,” a tactic of calling 10 of your friends and asking them to call 10 of theirs, with an app provided to help you. This kind of peer-to-peer contact often took place under the aegis of particular interest groups, like the NAACP and the Sierra Club: I learned about the Environmental Voter Project (EVP) from both the Citizens’ Climate Lobby and the Environmental Action wing of my Unitarian congregation.

EVP uses data analytics to find people who say that environmental issues are important to them; when they search election data bases, however, they find that many of these do not vote. They used phone bank and texting tactics in every kind of election from 2017- 2019 “as a behavioral intervention opportunity to build the habits of being a good voter…. using every election as an opportunity create habitual environmental voters….We’ve spent years leveraging the latest behavior science to test which messages work best at turning these environmentalists into better voters.” By 2020, they were “ready to mail, text, call, and send digital ads to these environmentalists using proven messaging, with over 4,000 trained volunteers to help us.”

Starting in the late summer before the election, an email would arrive in my inbox once or twice a week setting the day and hour of an upcoming work session in a particular state. I would go to the site via Hustle.com, press the scripted query about people’s voting plans 100 times (making 100 individual contacts), then sit back and wait for replies.

In these online “conversations” we congratulated people for voting, gave them information about their state voting website or their City Clerk’s telephone number, explained how to register for and use absentee ballots, provided due dates for filing along with specific locations of City Offices and drop-off boxes and links where they could check their voting status as they went through the process. We even had a polite script with an apology and promise to take them off our lists if they cussed us out for texting them in the first place. As this was a bipartisan campaign to get out the vote, and although most environmental voters were Democrats, I sent “thank you for voting” messages to people from both parties.

Click campaigning had very successful outcomes: James Zarroli explains that a “Texting Election” works so well because “Unlike regular mail or email, text messages are almost always read by their recipients, usually within minutes after they’re sent […] The average person looks at their phone every six seconds.”

In 2020, “of those 1.8 million environmentalists targeted by EVP, more than 600,000—or about 33 percent—voted early. It’s “a truly astounding number when you consider that these are almost all first-time voters,” said Nathaniel Stinnett, EVP’s president. “It’s also astounding when you consider that, in many cases, those voters outnumber the margin between Trump and Biden in key battleground states.”

Stacy Abrams’ Strategy and Tactics to Turn the Senate Blue on 5 January 2021

Horrified when the President commanded that our mailboxes be hauled away from our streets, our regional postal distribution machines sabotaged, our post offices understaffed, and used his bully pulpit to declare mail-in ballots were fraudulent, we white voters in 2020 only got a mild dose of the years-long voter suppression that Americans of color experience in every election cycle.

Voter suppression had been forbidden by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, including specific oversight provisions for southern states with especially bad records. As it became evident that whites would soon become a minority demographic in America, there were concerted nation-wide efforts to keep people of color from voting.

In a 2013 case, Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court of the United States found a key provision ordering “preclearance” or oversight of elections in traditionally suppressive states unconstitutional. States like Georgia quickly seized the opportunity to disenfranchise their burgeoning populations of peoples of color.

When Stacy Abrams, a longtime State Representative and Democratic Leader in the Georgia House of Representatives (also an author and serial entrepreneur), ran for Governor in 2018, she discerned widespread disenfranchisement of Black, Latinx, and poor voters. In her book, Lead from the Outside: How to Build a Future and Make Real Change (published in 2019), she observed that:

“Poor communities found themselves without equipment for voting, including missing power cords and antiquated machines. Other voters arrived at their polling stations only to be turned away because they’d been illegally purged or because the poll workers didn’t have enough paper for extra ballots. Some stood in hours-long lines, while their compatriots had to give up and go back or work or risk a family’s already meager paycheck. This is how the game of elections gets rigged.”

Abrams narrowly lost the 2018 gubernatorial election. A brilliant strategist, she determined to fight voter suppression on both the national and state level:

“I believe we can fix it. Not simply by dismantling what has been carefully constructed by centuries of patriarchy, racism, classicism, and bigotry – no one has that kind of time. Instead, we have to hack it. Figure out its flaws, identify backdoors, and overwhelm the system. Consider this my call to arms.”

Her strategy in a given political situation is to analyze the lines of power, figure out how decisions are made, and then “hack” it by coming at the issue from an unexpected direction. Where the usual campaign strategy is to persuade already-registered voters to support your candidate. Abrams’ “hack” was to focus on getting never-voters to register for the first time.

The New Georgia Project took note of shifting population demographics in a state where a “New American Majority,” consisting of people of color, 18-29 year-olds, and unmarried women, made up 62% of the population but only 53 % of registered voters. To get that 9% was the strategy. This was achieved through:

- Meeting new voters where they are – in churches, on college campuses, in their neighborhoods;

- Sharing information about how to register and how to vote, turning new registrants into voters, many for the first time ever;

- Engaging African-American Churches.

Far from going it alone, Abrams called on a wide variety of voting rights organizations long active in Georgia. Black Votes Matter, Women Talk Black, When We All Vote, Roll to The Polls, and the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America as well as a plethora of Black Women’s sororities and civic clubs had built a backlog of political will in communities of color that provided a well-trained, eager pool of participants in her drive to “turn Georgia Blue.”

The Result? Abrams’ coalition brought out 800,000 new Georgia Voters who carried the State for Biden and then turned the Senate blue in the January 5 Senatorial run-off election.

Abrams also created Fair Fight Action to register voters and get them to the polls on election day. They worked in all of the swing states (the ones with narrow margins between Republicans and Democrats). Here are some of their tactics:

- Fair Fight Action brought two important legal cases, suing the Georgia Secretary of State‘s office in 2019 over unconstitutional voting issues, and was a party in Curling v. Raffensperger to get rid of old voting machines;

- They fought voter intimidation by forming a coalition, the Voter Empowerment Task Force, including the Georgia NAACP, Black Voters Matter Fund, and the Georgia Coalition for People’s Agenda;

- They conducted phone banking, texting, voter observation (poll watching), and voter protection;

- They did fund-raising on behalf of candidates.

Stacy Abrams has just been nominated for the Nobel Prize for her work on Voting Rights.

How Progressives Counter-Strategized: Organizing Against Lies and Sabotage

It is evident that individuals are much too puny to change the course of history, but when we build alliances with multiple organizations, democracy can prevail.

However, we have a problem. A product of enlightenment reason, democracy depends on covenantal rationality.

First, the numerical count which gave Biden a tidy margin of victory in both the electoral college and the popular vote depends on American citizens reasonably accepting facts. Second, Electoral procedures like the certification of the count (first in states and then before the Senate) depend upon our adherence to long-agreed covenants like the Rule of Law and the provisions of the Constitution.

Adam Gopnik, in the New Yorker, explains how fault lines in these reasoned covenants that undergird constitutional democracy can rupture:

“America itself has never had a particularly settled commitment to democratic, rational government.. . the rule of law, the protection of rights, and the procedures of civil governance are not fixed foundations…but practices and habits, frequently threatened, frequently renewable.”

The possibility that Donald Trump may be suffering a mental delusion that he has actually won the election does not explain why the majority of Republicans are willing to collude with that delusion.

Trump didn’t create the Republican party: the Republican party laid the groundwork for Trump.

As Paul Krugman puts it, the problem is that “The U.S. right long ago rejected evidence-based policy in favor of policy-based evidence – denying facts that might get in the way of a predetermined agenda.” And that agenda, like Hitler’s, is power at any price, including the “big lie” that Trump won the election and enforcement by brutality. Trump and his Republican allies did everything they could – from court cases against swing states for their electoral procedures to personally threatening state legislators and election officials – to sabotage the Democratic victory that had already taken place.

Fortunately, a variety of progressive and left-wing groups (usually at odds with each other) formed a coalition to avert what they saw coming. Long before the election, they not only realized that Trump would deny the results but determined what tactics he would use to subvert them.

“At each juncture,” writes Alexander Burns in “How Democrats Planned for Doomsday, “the activist wing of the Democratic Defense Coalition deployed its resources deliberately, channeling its energy towards challenging Mr. Trump’s attempts at sabotage.” They saw how he called out the most brutal of his supporters like the Proud Boys and the Boogaloo Army to stage violent demonstrations, and that the intent of these uprisings was to foment the “civil war” between the races.

To avert such a disruption in the post-election period, the Democratic Coalition decided not to hold any demonstrations at all. Their key strategy was to focus on “seven swing states who would play a key role in determining the integrity of the election.”

One of these was my own state of Michigan, where armed militias threatened to kidnap and execute our Governor (for the crime of criticizing Trump for not doing enough against the pandemic) and where bands of thugs stormed into our Capitol building, armed and threatening.

After Biden handily won Michigan, Trump invited two state legislators to the White House to intimidate them into throwing out our votes. The Democratic Defense Coalition swung into action: they organized effective phone and letter-writing campaigns, publicized the fact that our Attorney General was preparing to sue the two legislators, and sent delegations to the airport to picket them going to and coming from Washington. As a result, they refused to deny the validity of Biden’s victory.

The Outlook: Granular Politics Must Go On

Unfortunately, all of this is still going on. As I write, Republican Senators have kept Trump from being indicted for fomenting the January 6 insurrection.

More than a hundred bills to suppress the vote are moving through state legislatures.

The State of Arizona lost a bid by only one vote to force election officials to turn over the state’s ballot boxes under threat of imprisonment.

A Michigan legislator who refused to cave into Trump has been removed from his post as chair of the state Republican party and replaced by the Trumpist who organized 19 buses for the attack on the Capitol.

The work of participatory democracy is long and hard, planning meetings tedious in the extreme, and devising effectively granular tactics exhaustingly meticulous: Nevertheless, our covenant to democracy demands that we keep at it.

Or, as Adam Gopnik puts it, “The way to shore up American democracy is to shore up American democracy—that is, to strengthen liberal institutions, in ways that are unglamorously specific and discouragingly minute.”

Indeed, “granular politics” can be boring and repetitive nitty-gritty work. But we cannot give up. And so far, we have persisted and democracy has prevailed.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.— In the Featured Photo: Save Democracy Photo by Fred Moon on Unsplash