The pandemic currently spreading across the globe is not slowing but accelerating. COVID-19 has become a factor for national and global security with few equals in modern history. If morbidity and mortality rates continue to rise along the present trajectory, it is likely that many countries will be looking to their armed forces to engage in the response.

Further, it is not inconceivable that this will become a concern of such magnitude, within countries, across borders and regions, that a time may come when it will seem judicious to call on the United Nations to draw on its peacekeeping authorities to act. We know that governments and the UN have done so in the past and to some degree with COVID-19. Virologists have said another pandemic is highly possible, really not “if” but “when”, and therefore it makes sense to look at the interface of the military’s role in health emergencies.

Perhaps Italy was the first place outside of Asia where the general public became aware of the role the armed forces can play in the fight against the virus – probably because Italy was also the first country in Europe to be hit by COVID-19. It happened in March 2020 in the small town of Bergamo, the epicenter of the pandemic at that time. Municipal hospitals were overwhelmed but so were cemeteries. The army, as always the help of last resort, was called to move the coffins to out-of-town facilities and television repeatedly presented the news to a panic-stricken nation. Here is a video of what happened, it needs no translation:

The dramatic role of the Italian military (the harrowing scene was repeated five times in Bergamo, from March to April) remained in the nation’s collective memory and has helped shape the average Italian’s reaction to the pandemic – ensuring that people famous for their indiscipline (flouting government rules are a national pastime) were surprisingly compliant in following lockdown measures.

Most modern armed forces have special capability and characteristics which are essential to bring to bear in health emergencies. They are trained in the ability to command and control people in chaotic situations and environments. They typically have integrated military medical systems with trained personnel and equipped units, as well as logistics resources and competencies, crucial in emergencies. Further, operating under civilian authority they are able to provide backup support in securing key logistics hubs or assisting police with public safety.

I. National Responsibilities

There is no one formula that fits all countries, but most have rules and regulations which, on the one hand, prohibit domestic military enforcement (keeping order is generally left to the civilian police) and on the other, authorize humanitarian assistance and medical support. Such support can entail enforcement of quarantine zones, emergency treatment, maintenance or restoration of medical drugs and equipment, and more broadly any measure needed to safeguard public health.

In many jurisdictions, the space left to the military is further circumscribed. There may be lines drawn separating what the national government can do without authorization by the province or state and what the latter can do as sub-national governing bodies. With this caveat, let us look at a few specific examples of how this translates into rules and guidance for national political authorities and the military in determining behavior in a pandemic situation.

Canada

The basis on which the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) respond in a national health emergency is the National Defence Act and the Queens Regulations and Orders, and framed in the Capstone CAF doctrinal publication entitled “Canadian Military Doctrine”, which states:

“Canada must be able to respond to potential transnational threats whether they are natural disasters (such as hurricanes and floods), terrorist attacks, or pandemic health crises. To do so, the Government of Canada has made the defence and provision of assistance to the citizens of Canada the number one priority of the defense mission.”

A national emergency is defined as “an urgent and critical situation of a temporary nature that seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians” and must be so severe it necessitates measures that exceed both provincial competencies and the normal authorities of the federal government.

Initiated by civilian authorities, requests for health emergency assistance require authorization from the Governor in Council or the Minister of National Defence (MND) who then directs military leadership to provide appropriate complementary support to the civilian authorities to save lives, prevent or alleviate human suffering. Such assistance ranges from limited supplies and equipment to a major deployment of CAF resources.

Since April 2020, the Canadian military COVID-19 emergency health assistance effort has been underway in Quebec and Ontario. Nearly 1,300 members have been deployed in long term care facilities, working collaboratively with provincial partners and medical staff in the homes to maintain staffing levels and help with infection control and prevention. They assist with the day-to-day operations, coordinate, and provide medical care, and general support.

United States

Under United States law, the military is prohibited from taking an active role in domestic enforcement. The President is empowered to take action for a major disaster through the provision of “essential assistance” which can include distribution of medicine and food and the use of federal resources (military personnel, supplies and facilities) to provide emergency medical care.

Under provisions of the 2018 U.S. Defense Support of Civil Authorities, guidance is provided to plan and conduct activities which can “include…. medical countermeasures distribution, pandemic influenza and infectious disease response, mass migration, and civil disturbance operations.”

In the COVID-19 context, assistance has been provided to States in the form of field hospitals, hospital ships, critical facility equipment, medical and personal protective supplies, as well as the deployment of military emergency medical personnel to laboratories, other facilities, and involvement in civilian testing.

In recent weeks, President Trump has said with respect to the distribution of vaccines (presumably should there be one approved as safe and effective), that “the military is ready”.

European Union

European Union (EU) Member States are individually responsible for responding to major public health major emergencies within their borders and can use appropriate means, including the military. The EU’s role in the field of public health, as established by the “Treaty on the Functioning of the EU”, is limited to complementing national policies of the EU Members, coordinating their actions, and facilitating communication and the exchange of data between the European Commission and the EU Members.

However, The EU Health Security Committee is authorized to coordinate and take measures to protect public health. The EU military has supported national authorities by providing personnel, material, logistics, and transportation both within Europe and overseas.

Any role the military has had in Europe so far has been played at the national level. Action has followed two directions: (1) avoid proliferation among the armed forces by scaling back operations and imposing stricter rules considering armed forces live in close quarters; and (2) drafting specialist army, navy, and airforce units to help the government address the virus.

For example, as reported by Reuters in April 2020, Germany had mobilized 15,000 soldiers to help local authorities tackle the crisis and Poland had activated thousands of troops to patrol streets under lockdown, disinfect hospitals and support border control.

Russia

There is no special legislation aimed at the regulation of issues related to public health emergencies and epidemics and the military. The outbreak of epidemics is considered an emergency, and all rules prescribed by the Federal Constitutional Law on Emergency Situations apply.

The Russian armed forces have been called on to support civilian emergency and medical infrastructure. During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian military has sent medical supplies equipment to several countries – including a military plane loaded with medical equipment, ventilators and masks to the United States, as reported by AP on 1 April 2020.

Russia also provided army medical personnel abroad, as was the case with Italy. The Italian experience with Russian military aid appears to have been mixed. The far-right Lega headed by Salvini welcomed it, but criticisms emerged from other quarters as it appeared to be of little help. La Stampa, a major paper in Italy, reported that 80% of it was “useless”.

What we do know is that a 100-strong contingent of Russian soldiers operated in Bergamo, and reportedly took care of 93 patients; 62 of them recovered and were discharged while other Russian personnel were filmed disinfecting buildings in the area. However, the operation was abruptly canceled and Russian soldiers were brought home in early May as the coronavirus hit Russia, with 10,000 confirmed cases in just 4 days in a row.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In most African countries governing laws designate health emergency management responsibility to the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Interior. One key for effective intervention on the continent would be to have national-level compact well-equipped and well-staffed organizations focused on carrying out emergency operations. Such strategic bodies, called Health Emergency Operations Centers (HEOC) are relatively common in other areas of the world but are new in Africa.

A good example of how the HEOC concept works comes from Senegal. Here, not only the Ministry of Health is engaged during a health emergency crisis, but also other ministerial entities such as the Ministry of the Interior and most notably, the Ministry of Armed Forces. All of them, the military included, are called upon to coordinate an effective administration of emergency and disaster assistance.

Yet, Africa remains one of the areas most affected by emergency situations and disasters and still too few African countries have followed Senegal’s example and possess HEOC. As a result, emergency and disaster management interventions continue to be carried out in a relatively non-systematic manner.

India

India’s Constitution and relevant laws provide the basis for declaring a disaster and the exercise of administrative powers to conduct surveillance, isolate or quarantine infected or potentially infected individuals, ensure availability and rapid distribution of pharmaceuticals and supplies. Moreover, the health care or disaster management workforce can be further expanded as needed by co-opting personnel from other agencies and jurisdictions under a unified command structure – thus presumably including the armed forces.

Early-on when the pandemic hit, the Indian armed forces helped in many ways. They set up quarantine facilities and health centers, made available military hospitals and provided medical personnel to assist civilian authorities in screening and other key areas. It contributed essential items such as masks, PPE, hand sanitizers, and foodstuffs to vulnerable populations. It has also helped to evacuate stranded Indian civilians from virus-affected countries, helping to repatriate them.

China

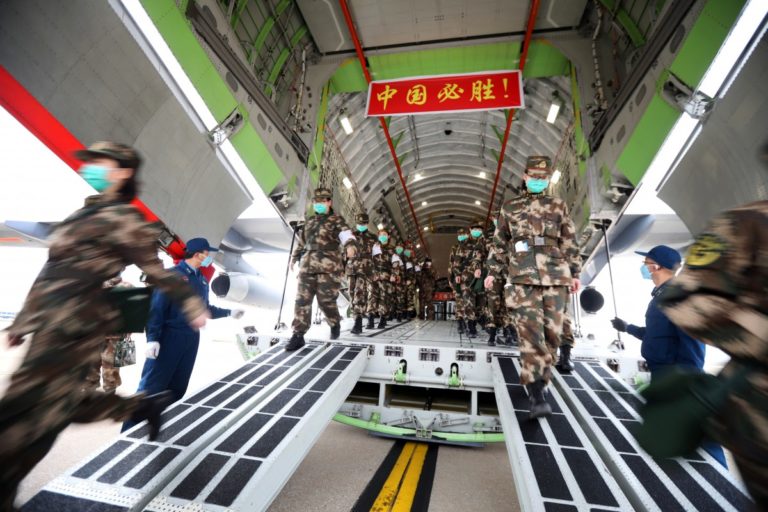

The Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) had been involved in responding to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003 and the 2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Thus, under existing authorities when the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan was determined a national health crisis, the PLA was activated and brought more than 4,000 military medical personnel into the region, with the PLA Air Force airlifting both medical personnel and supplies.

Assistance was provided in carrying out quarantine measures, health surveillance and testing. Further, some 200,000 militia from other military districts, as well as more medical personnel and supplies, were brought in via bus and high-speed rail to the Wuhan region. Once COVID-19 was seen as a national threat, the Chinese armed forces were massively engaged and at least with respect to containing the spread, effective.

II. International Armed Forces Interventions

The United Nations has had peacekeeping operations throughout the world, and in some cases for decades, These were specific to each instance because the UN can only deploy military personnel on the basis of a UN Security Council Resolution authorizing it to do so. The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) is the entity charged with overseeing such endeavors.

In 2011 the UN Security Council passed a resolution on HIV/AIDS which addressed one health aspect of peacekeeping operations, namely the need for HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention of assigned personnel.

In 2014, it passed a resolution on the West African Ebola outbreak, the first UN Security Resolution to acknowledge a health issue as a threat to peace and security. The resolution did not lead to military intervention per se but did include supporting cooperation with the peacekeeping operation in Liberia, known as the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL).

Depending on the situation and the mandate, peacekeeping COVID-19 activities have included implementing proper hygiene and sanitation policies, distributing protection kits, and combating misinformation. DKPO women play a particularly important role in gaining the trust of communities.

Any peacekeeping health emergency assistance must rest primarily with the relevant civilian United Nations specialized agencies, funds, and programs, as well as the range of independent, international, and local NGOs which are usually active alongside a United Nations peacekeeping operation.

In some cases, however. peacekeeping tasks were very similar or overlapped with those of the humanitarian actors in the same area. This overlap was the result of the absence of clear delineation and guidance in defining the limits on UN peacekeeping operations and its role in protection in relation to that of health emergency actors. Thus, some peacekeeping missions have been mandated to provide humanitarian assistance, others to facilitate access, and others without any explicit humanitarian role.

The concern for the blurring of duties was expressed by a former president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Cornelio Sommaruga who considered such separation, including the delivery of medical assistance to civilians, essential:

“UN military missions are an essential component of successful conflict management; in certain anarchic situations they may prove indispensable in securing respect for international humanitarian law and thus restoring the necessary security environment for the conduct of humanitarian activities. Peacekeeping, and especially peace-enforcement operations, should be clearly distinct in character from humanitarian activities. Military forces should not be directly involved in humanitarian action, as this would associate humanitarian organizations, in the minds of the authorities and the population, with political or military objectives which go beyond humanitarian concerns.

III. The Bottom Line

There is now profusion and confusion at national and international levels of how to effectively use military capabilities in responding to the existing pandemic, much less the next.

What is clear is that there will be some role for the military in the future. The challenge will be how to protect civil liberties, how to avoid infringement on healthcare and humanitarian professionals, and how to establish an exit strategy for the military from the outset.

The international community has shown it could join together when there is a global need, as in the case of the “Access to COVID-19 Tools, -the ACT-Accelerator”, and UN Security Council sessions on HIV/AIDS and Ebola. Before the next pandemic, there is little time to get better prepared in sorting out how to take effective and proper advantage of military competencies.

As COVID-19 positive cases spike to new unimagined levels, with civilian health and welfare authorities over-stretched, clarifying when and how armed forces are called to action becomes an urgent priority everywhere.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed by Impakter contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the Featured Image: Ukrainian military aircraft IL-76 has delivered a batch of coronavirus tests and medical assets from China, 23 March 2020 Source: Міністерство Оборони України