Housed within Black Forest town of Freiburg, the Rolf Disch Solar Architecture Firm is one of the most renowned solar pioneers in Germany and a driver of Freiburg’s commitment to a sustainable future.

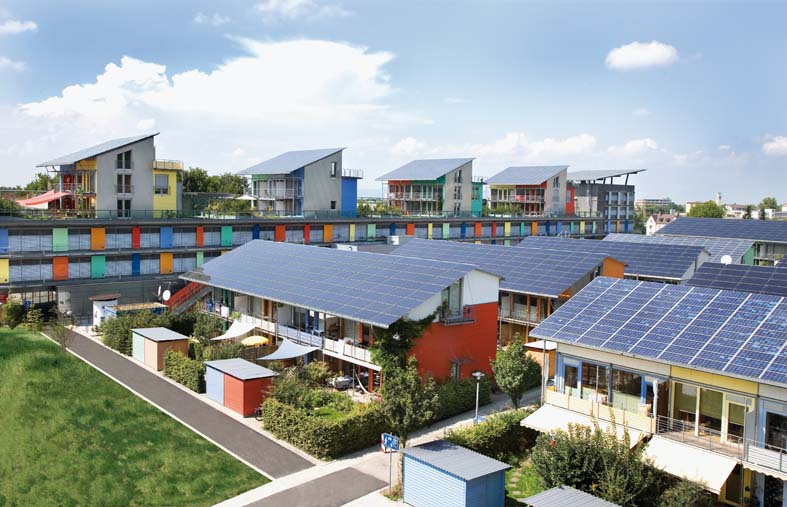

In the photo: The Sun Ship in Freiburg

In the photo: The Sun Ship in Freiburg

Founded in 1969, Rolf Disch has since become a household name in Germany in addition to the green infrastructure and design communities. In this seemingly quiet Black Forest region, a striking vision of incorporating sustainability and solar technologies into design came together. This vision led to the fruition of the world’s first Solar Community with innovative Plus Energy Houses that produce more energy than they consume, Quartier Vauban’s Solar Settlement. In light of rapid global change and urbanization, can the visionaries at Rolf Disch provide clues to achieving sustainable communities and green infrastructure? I got a chance to talk to Dr. Tobias Bube, one of the lead directors at the firm and an expert in energy economics.

In the photo: Dr. Tobias Bube at the Rolf Disch Solar Architecture office.

In the photo: Dr. Tobias Bube at the Rolf Disch Solar Architecture office.

Q.How did the Solar Architecture Firm come to be, the solar settlement?

The first projects were schools and senior citizen homes along with a few housing projects, but there were plans to build a nuclear power plant nearby in the town of Whyl. Consequently, there were large protests against its construction. People started to think that it was not enough to say no to nuclear, rather we had to come up with an alternative. Since 40% of total energy consumption comes from constructing and using our buildings, it becomes a big issue for an architect. Therefore, we started to think a lot about energy efficiency first, but all of a sudden solar photovoltaics became available.

At first, it was not economically viable, but then we started to apply it, and in a number of early housing projects, we included it as an option. In 1994, we decided enough of the experiments; Mr. Disch decided that he would do it with his own house, the famous Heliotrope. Obviously, this is an experimental building and does not fit into the usual housing or commercial building model, so the next step was to develop the solar settlement, something that fitted into local building regulations more easily. The solar settlement has 50 terraced houses and the Sun Ship is mainly a commercial and retail building with penthouses on the top, running parallel to the settlement to block noise from traffic.

In the photo: The Solar Settlement in Freiburg – The Sun Ship with the penthouses in the background.

In the photo: The Solar Settlement in Freiburg – The Sun Ship with the penthouses in the background.

Q. Solar technology for residential communities is notoriously expensive, so how difficult was it to find funding?

It used to be expensive. Today PV electricity is a lot cheaper than what households pay when they buy from the public grid. Back then, it was kind of difficult because the politicians did not really believe in it, and there was no bank to finance it. They thought we were completely crazy, and it was the same with development companies. Therefore, Mr. Disch founded his own development company and appropriated private funds from Alfred T. Ritter and Marli Hoppe-Ritter, of Ritter Sport chocolate. The Ritters wanted to help support sustainability projects because they could not find uncontaminated Hazelnuts for their chocolate bars for years after the Chernobyl incident. With financial support, we were able to build and sell the houses.

We also came up with “green” real estate investment schemes, so people did not have to buy a complete house, you could buy shares. When we did the same for the refinancing of the Sun Ship later, the western housing and financial crisis started. All of the sudden we could sell shares saying, there is no bank involved because we were controlling the financial schemes.

People were afraid of investment schemes at that time that were not transparent, but we could say we are the architects, the developers and the issuers of the shares, so we were more transparent than banks or most of the products of the stock market. It took a lot of time, 6 years, to develop and finish the project. The last thing we built was the penthouses on top of the Sun Ship.

In the photo: A Penthouse on the Sun Ship

In the photo: A Penthouse on the Sun Ship

Q. Are there plans to expand Vauban? Do you have other ongoing projects which include solar communities?

Yes, but at the moment, not in Vauban. There is still some land in the southern part of Vauban, but other firms are developing it, and unfortunately with lower environmental ambitions. We are working on another project planned in Freiburg, a little smaller. We are going to do a massive six-story construction, mainly out of wood. The black forest is here, so we have the wood. Production of concrete produces large amounts of CO2, so we decided to build a six-story wooden building from local resources. Another project is a 50,000 m2 residential complex in Berlin-Kreuzberg, near the city center. Two families from Berlin asked to have one or two Plusenergie Houses, but it would be expensive to plan a single house 800 km away from where our office is, so we suggested that they find more people, and if they got enough people for ten houses, we can talk about it again. They came back with 500 families, so we are working on that project. Additionally, the first Plusenergie House is now under construction in France, which is difficult because in France energy is cheap because of the nuclear energy. It is still impossible to be competitive in France in terms of PV, so it is a construction for an idealist, not a pragmatist. And we are planning a new solar settlement of 190 residential units close to Basel.

In the photo: Pilot project “Moeckernkiez”, perspective (Rendering: Loomilux)

In the photo: Pilot project “Moeckernkiez”, perspective (Rendering: Loomilux)

Q. Do residents of the solar communities have a certain level of environmental literacy coming in, or can they become educated by living in the community? Is Plusenergie design behavior-changing?

Let’s say one part of the people that moved into the Vauban settlement in Freiburg became more conscious, while some already had environmental literacy. Others move in for other reasons, like making money from Plusenergie Houses. The insulation of the houses actually works really well also for sound insulation. People can practice piano and play their instruments whenever, so there are lots of musicians in the Solar Settlement. In terms of using your car, that also becomes a more educational experience. Many families do not own a car, so attitudes about cars may actually change. I also think people would think twice if they had to change their fridge. They would now probably buy an efficient one because it doesn’t make sense to save energy all around you but keep older appliances etc.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Related articles : HANOK – THE REMODELING OF A TRADITIONAL KOREAN HOUSE article by DANIEL TAENDLEROIL SPILLS: A DOUBLE STANDARD WORLD article by Hannah Fisher-Lauder …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Q. So it seems like the house is “passively” doing it all. Could this pose a problem in terms of residential awareness of sustainability and actively being eco-friendly?

In terms of saving energy for room heating, the house does it for you. One resident stated that this was an adjustment, “I would love to save energy, but I can’t because the house does it for me.” Heating costs are now around 150 euros a year, as compared to an average of 2,000 euros in a conventional building of the same size in Germany. You have to be careful with functionality, but we tend to keep things simple. As soon as you have a lot of complicated processes that require a lot of activity by the people using the houses or offices buildings, they may not get on board. Your usual inhabitant does not have a degree in engineering, so we believe that everything has to be kept easy, otherwise people will not operate the systems appropriately, and less or no energy will be saved.

In the photo: Internal view of the Rolf Disch Solar Architecture office.

In the photo: Internal view of the Rolf Disch Solar Architecture office.

There is a lot of Smart Tech for houses and Smart Cities, which is fine, but don’t make it too complicated. They are not able to manage it. Here in the office building, we have a very simple cooling system. Ventilation flaps can be opened or closed manually to cool down the temperature in the office during summer nights which are usually 10 degrees colder than during daytime. The last to leave the office in the evening in summer opens them; the first to arrive in the morning closes them. We could have had an automatic system, but that requires maintenance and can become expensive, so we kept it simple. Now, once people were complaining that in November, their office was too cold because people were leaving the flaps open. So even though the idea is so simple, they had not understood that this was just meant for summer conditions. So, sometimes there are miscommunications even with simple systems, so now imagine that you have a really complicated system – what would happen with people operating it who are working in an office and who have a lot of other things to think about ….

Q. Moving towards larger issues facing architects and designers today, do you think that design can be used to address socio-economic equality and other issues?

We do what we can, but there are limits. Classic modernist architects thought that they built, and it would change communities all together, and they did but not always in ways they had originally thought. You have to be careful not to be over ambitious.

For example in Vauban there is this issue of car traffic. This is an energy issue and a social issue. If you keep cars outside of residential areas, it changes them. You can send your children outside without having to worry about traffic. It creates a social public space for people to come together.

All of the sudden, children could go to school by bike

In South America, city centers are often built with a lack of public space, so there are cars taking up these public spaces in very extreme ways. Bogotá, Colombia was one of the most dangerous places on the planet, but they had two mayors with some green ideas in regards to urban planning and transportation, so they changed it. There was a plan for another motorway going through the center of Bogotá, but the mayor said no. Instead, he wanted that street for buses and bikes only, and they banned a lot of the parking cars from the side streets, and this changed the surrounding area completely. All of the sudden, children could go to school by bike. There were more people in the street, and when that happens, the community becomes safer. Getting people in the streets creates safety in addition to having a nice functional public space.

In the photo: Street Space With Solar Shed

In the photo: Street Space With Solar Shed

Q. In the future, do you see solar communities as becoming a part of sustainable development in developing nations? What is the cost of installing these sustainable communities in comparison to traditional communities?

Yes, the thing about developing countries is there is more building activity than here. Most of these countries have hot climates. If we take our mission seriously; we have to come up with solutions for that and adapt the concepts to the climate. In Mexico and Oslo there is no difference in the design of an office building.

sustainable architecture means really adapting to the climate but also the socio-economic conditions

In the case of Oslo, they require very high heating environments, but in Sonora, Mexico it’s like building an oven and trying to cool it down with air conditioning. Therefore, the point is obvious: sustainable architecture means really adapting to the climate but also the socio-economic conditions. In the past energy was cheaper, so it was not something architects were even thinking about. I am presently negotiating projects in Mexico and Nigeria so we are trying to do projects in all of these places.. Also, architecture fees here in Germany are much higher than in Mexico and these other countries, so it is difficult to compete, but it works when you have local partner architects.

In the photo: Pilot project “Moeckernkiez” – view from the park (Rendering: Loomilux)

In the photo: Pilot project “Moeckernkiez” – view from the park (Rendering: Loomilux)

Q. I’m fascinated by the idea of embedding culture into the natural world in order to help save it with conservation initiatives. Do your sustainable communities help to bridge this gap?

Yes, this happened. An example is the citizen-run food cooperative of the Quartier Vauban, in which all community members can join. Additionally, the community has developed its own car-sharing program. Our new project near Basel incorporates a communication platform to help residents share property, so if a family needs, for example, a lawn mower or some sort of appliance/tool, they can use this platform to connect with other members of the community – so why should 190 households buy 190 lawn-mowers, when it is enough to buy 5 and then share them?!

These programs organized within the community empower residents to live how they want, and organize themselves how they want. It is simple to offer this platform in the beginning, and then let the community take over. We will also have E-Bike sharing in the new Basel settlement and larger bikes with carriages for shopping etc. This is all part of the rent that they pay. When people get closer and have more contact and opportunities to communicate, it is good for community building. However, sometimes it can be too much, so privacy is an issue sometimes. Too much contact and people get fed-up and in the long run it undermines your original idea. This is also an architectural issue, to have public and private spaces, so this is something we are thinking about moving forward.