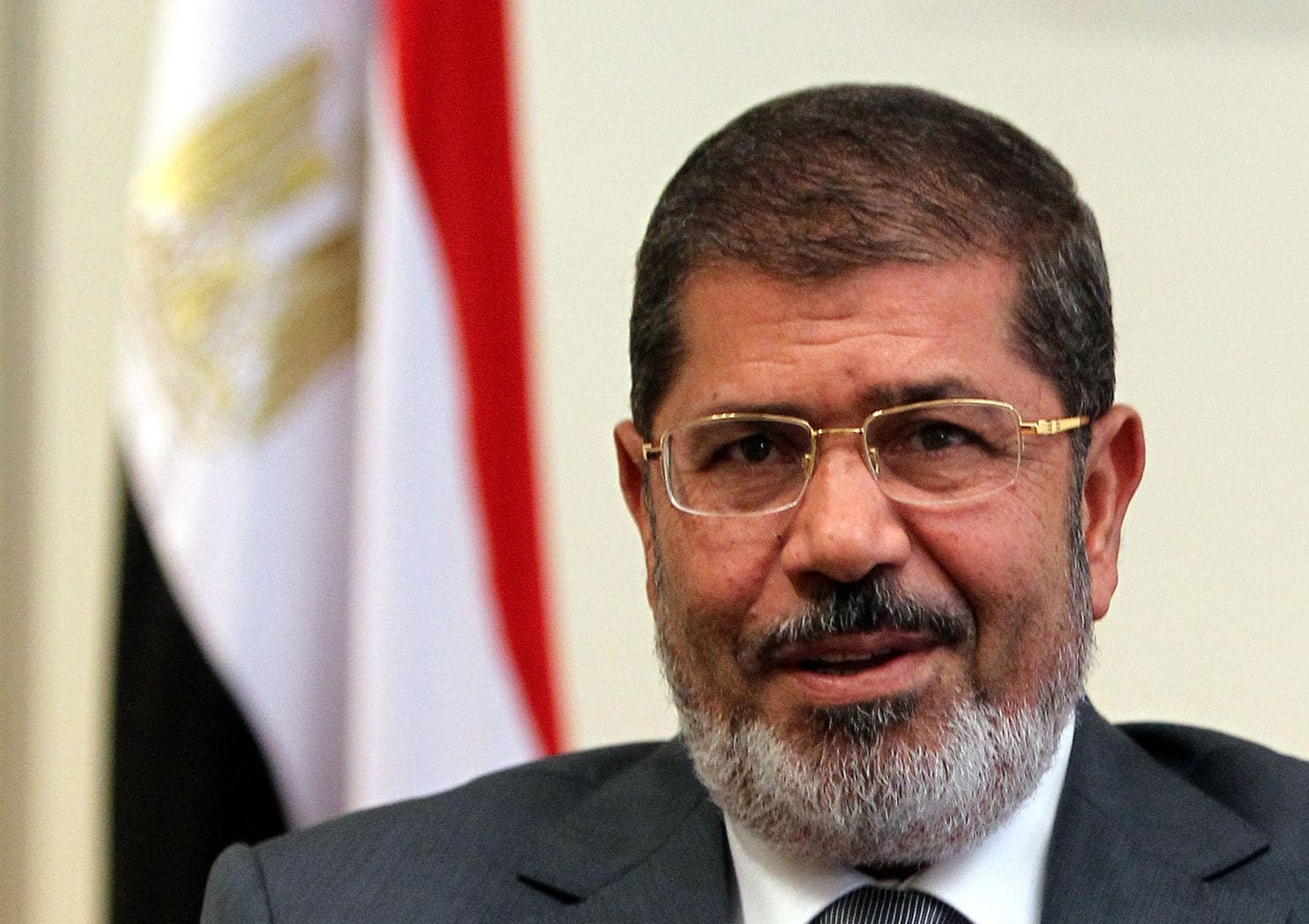

Former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi passed away last Monday after collapsing during a court hearing where he was being tried on espionage charges. Morsi, a former official in the Muslim Brotherhood, was reported by state sources to have spoken to the court as part of his defense before falling to the ground unconscious. He was quickly taken to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival at the age of 67.

Morsi was elected to the Egyptian presidency in 2012 in the country’s first free and fair democratic elections, before being deposed by the military a year later. His former defense secretary, Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi, has since taken control of the country, instituting a crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood members including Morsi.

A Victim of the System

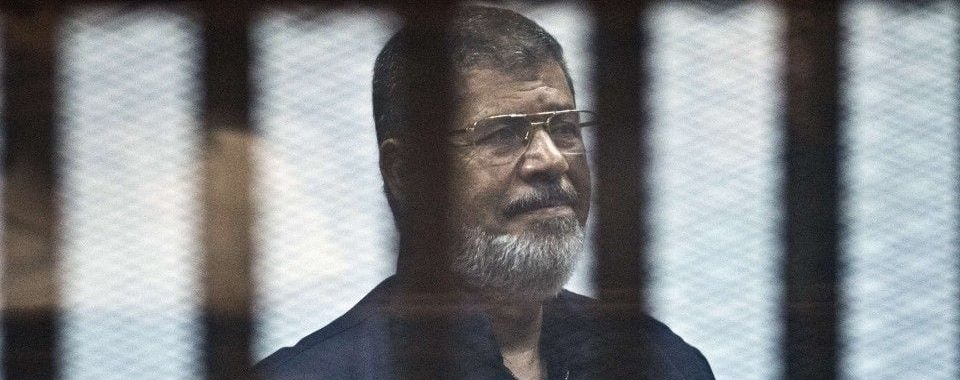

Many observers noted that while the death of the former head of state was tragic, it was not entirely unexpected, with reports of abuses and poor prison conditions circulating since the time of his imprisonment. A March 2018 report by the Detention Review Panel noted that “Mohamed Morsi is receiving inadequate medical care, particularly inadequate management of his diabetes and inadequate management of his liver disease”, while Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director for Human Rights Watch, tweeted upon his death that the Egyptian government had failed to provide adequate medical care and access to his family, instead putting him in solitary confinement.

In that sense, Morsi’s death represents the accomplishment of what was likely the end goal of the Egyptian authorities; to keep him silenced and wait for him to die of natural causes rather than executing him directly. The latter move would’ve likely caused a stir and unrest among his supporters in the country, while also undermining the legitimacy and behavior of the Egyptian government in the international arena.

Photo credit: Madamasr.com

The Fall of Hope

In a way, Morsi’s demise reflects the death of the Egyptian experiment with democracy in addition to his own life. In addition to being the first Egyptian president elected in free and fair democratic elections, he was also the first non-military president in the country’s modern history, reflecting the hopes of many Egyptians that the country would begin to move away from military control after the fall of long-time autocrat Hosni Mubarak in 2011. In reality, the military is now more in control of Egypt than ever before, with Sisi in particular solidifying his power after a referendum was passed last April amending the constitution to allow him to stay in power potentially until 2030.

Furthermore, while Morsi’s detractors argue that his time in office coincided with civil unrest, a crumbling economy, and attempts to consolidate power in the hands of his allies, it cannot be denied that the current regime has also failed in these respects. The country continues to deal with insurgents in the Sinai Peninsula, while the capital has faced two roadside bomb incidents near the Pyramids of Giza within the last seven months. Meanwhile, living conditions for ordinary Egyptians continue to deteriorate, with a World Bank press release noting that “some 60 percent of Egypt’s population is either poor or vulnerable, and inequality is on the rise”. This comes at a time when the Egyptian government has embarked on a debt funding spree since Sisi’s tenure began, with government debt obligations (foreign and domestic) at 97% of GDP and 38% of the national budget dedicated to just paying off interest alone. Lastly, it’s no stretch of the imagination to conclude that the recent constitutional amendments constitute nothing short of a power grab by Sisi and his military allies, not only extending the potential length of his presidency but also granting him the authority to appoint members of the judiciary along with a third of the members of a new house of parliament.

While Morsi’s rule was by no means perfect, it cannot be argued that Sisi has ruled any better. The only difference between the two is that Morsi had the benefit of electoral legitimacy and the promise of establishing a democratic precedent, while the same cannot be said of his successor.

Photo credit: AFP/Getty Images

Going Out with a Whimper

The manner in which the Egyptian press reported Morsi’s death accurately sums up the authorities’ treatment of him while he was still alive: providing the bare minimum of what was necessary and making sure it was kept quiet. Nearly all of Egypt’s newspapers reported the same 42 word story scripted by the government, which failed to even mention his previous role as president. In addition, the only foreign nations to release statements after his death were Qatar and Turkey, which were already known to have sympathized with Morsi, ironically providing more condolences than his own country of birth.

In most instances, the death of a former head of state is an occasion marked by reflection, remembrance, and solemnity by the government and the people. Morsi however leaves this life with a controversial legacy, the promise of what could have been for Egyptian democracy, and a whimper, the government of his nation determined to suppress any memory or mention of him.