Science for Sustainable Development: An Old Relationship Reshaped

The connection between science, the consolidation of peace, and the pursuit of human welfare is not new. In November 1945, the UNESCO Constitution adopted an already commonly accepted idea that cooperation in the scientific domain, among others, was a necessary path to peace and prosperity. According to the Constitution, such cooperation should aim to counter ignorance and prejudice, and ultimately contribute to the unrestricted pursuit of objective truth. To secure lasting effects, it should be founded upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of humankind, and brought forward by the free exchange of ideas and knowledge.

Major science conferences of recent decades (for instance the World Conference on Science, 1999, the 6th World Science Forum, 2013 and more recently the 4th World Social Science Forum, 2018) echoed this idea with an increasing emphasis on the responsibility of science for sustainability.

This picture is confirmed by data; statistics show a growing worldwide acceptance, especially in the non-OECD countries, of science technology and innovation (STI) as driver of development and sustainable growth. This is exemplified by the continuing increase in the Gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD), which encompasses both public and private investment, despite the aftershocks of the financial crisis of the previous decade.

In The Photo: Much remain open to be elucidated as scientific innovation continues to evolve. Photo Credit: Chris Liverani/Unsplash

In The Photo: Much remain open to be elucidated as scientific innovation continues to evolve. Photo Credit: Chris Liverani/Unsplash

Similarly, it is interesting to note the growing belief in the importance of public support in researching and developing for the creation of knowledge and technology adoption – though much innovation is occurring without any such activity – in emerging and lower income countries, as opposed to the disengagement observed in many developed countries.

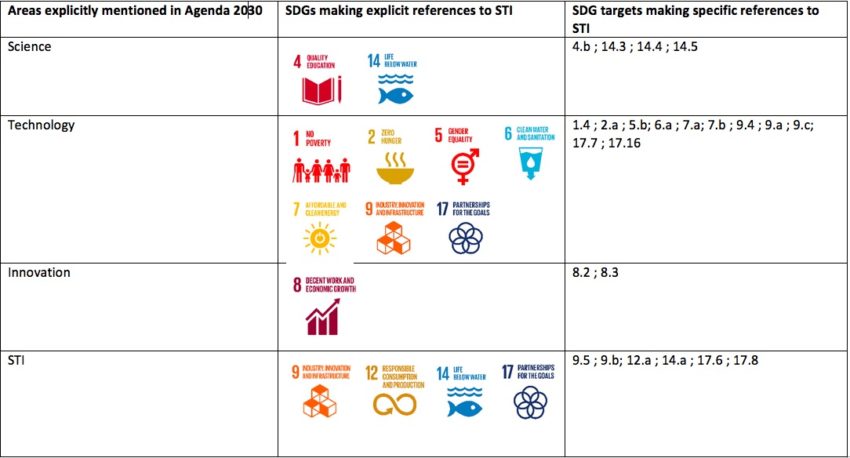

Reflecting this broad consensus, science, technology and innovation are woven into the fabric of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Its preamble reminds us of the immense opportunities generated by scientific and technological innovation, and the spread of information and communications technology.

In that spirit, science cuts across virtually all of the 17 SDGs, as well as their targets and means of implementation; it encompasses such areas as national investment in science, technology, innovation, the promotion of basic science, and science education and literacy. At the same time, science, technology and innovations are explicitly mentioned in relation to the attainment of twenty-three targets.

In The Photo: Agenda 2030 Table. Photo Credit: Nada Al-Nashif

In The Photo: Agenda 2030 Table. Photo Credit: Nada Al-Nashif

The 2030 Agenda was a main breakthrough; not only in that it reaffirmed the need for a holistic approach to science and sustainable development but, more importantly, it provided unprecedented political legitimacy. Similarly, the Agenda, with its vision of “leaving no one behind” and its emphasis on social justice outcomes, brought the relationship between science, sustainable development and human rights to the forefront.

Science and Human Rights: The Missing Link

The idea of linking science to human rights does not require substantiation. In fact, as in the case of the relationship of science with development, the connection was already acknowledged at the start of the UN system. The UNESCO Constitution establishes in Article I the direct link between scientific cooperation and human rights promotion.

Subsequently, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights laid down, in Article 27, the right of everyone “to share in scientific advancement and its benefits”. In 1966, the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications became a legally binding norm in article 15 1 (b) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

Despite early recognition, the interrelationship remained an aspiration and its operationalization stagnated. Beyond political agendas and power imbalances, a major obstacle was the lack of clarity as to the normative content and the practical implications of the right for all scientific fields. According to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), “governments largely ignored their Article 15 obligations and neither the human rights nor the scientific communities brought their skills and influential voices to bear on the promotion and application of this right in practice”. As a result, the right to science has been historically neglected.

In The Photo: The science-human rights relationship needs to be operationalized. Photo Credit: Josh Riemer/Unsplash.

In The Photo: The science-human rights relationship needs to be operationalized. Photo Credit: Josh Riemer/Unsplash.

Today, the types of challenges we are confronted with call for urgent efforts to forge the missing link. Major science conferences, including the aforementioned, expressed concern, inter alia, for the social imbalance and exclusion generated by environmental degradation, technological disasters, the democratic deficit in the debate on the production and use of scientific knowledge, the insufficient connection between natural and social and human sciences in problem-solving, the obstacles in the sharing of scientific knowledge and the uneven distribution of scientific benefits.

Actually, the nature of these challenges points to the centrality of human rights principles (such as equality and non-discrimination, participation and inclusion, accountability and transparency) in finding durable and people-centred solutions.

A critical step to allow the development of appropriate policies and programmes would be to provide a legal definition of the right. This is the task of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the body supervising the implementation of the ICESCR. It is currently working on a general comment on the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, which will provide an authoritative interpretation of article 15 1 (b) to clarify and systematize the understanding of science as a human right.

Interestingly, the Committee does not limit its reflection to the issue of sharing the benefits of scientific and technological advancements; construing this right in conjunction with other paragraphs of article 15, it actually considers the whole process of conservation, development and diffusion of science. Also, importantly, it looks, inter alia, at questions of agenda-setting in scientific research, science-society interface, access to scientific method and knowledge, and the relationship with intellectual property protection regimes.

In The Photo: States should facilitate and encourage open science. Photo Credit: Markus Spiske/Unsplash.

In The Photo: States should facilitate and encourage open science. Photo Credit: Markus Spiske/Unsplash.

A Right to Science: Insights from a UNESCO Recommendation

UNESCO, as the UN specialized agency in the field of science, was the first such entity to grasp fully the critical importance of elucidating the relationship between science and human rights, particularly for the disadvantaged and marginalized. After decades of oblivion, UNESCO sparked a global discussion amongst experts, which led to a first outline of principles, issues and challenges for the operationalization of the right (see the Venice Statement on the Right to Enjoy the Benefits of Scientific Progress and its applications).

Further to this broader exercise, UNESCO contributed through its International Bioethics Committee to unpacking the principle of benefit sharing, set forth in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (2005).

These efforts, inter alia, paved the way for the adoption, in 2017, of the UNESCO Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers. A main innovation of the Recommendation is that it sets forth a comprehensive vision for science, unequivocally anchored in a human rights setting. Among its many important principles, three deserve to be highlighted in this context. First of all, the emphasis on the responsibility of science towards UN ideals of human dignity, progress, justice, peace, welfare of humankind and respect for the environment. As a result, science should be fully integrated in efforts to develop more humane, just and inclusive societies.

In The Photo: Science, technology and innovation are woven in the fabric of the SDGs. Photo Credit: Alexandre Debieve/Unsplash.

In The Photo: Science, technology and innovation are woven in the fabric of the SDGs. Photo Credit: Alexandre Debieve/Unsplash.

A second feature relates to the need for science to interact meaningfully with society and vice versa towards tackling global challenges. This calls for the active participation of society in a democratic and horizontal manner in science and research, through the identification of knowledge needs, the conduct of scientific research, and the use of results.

Finally, the Recommendation promotes science as a common good. According to the text, this entails that public funding of research and development should be perceived as a form of public investment; the returns on which are long term and serve public interest. Likewise, States should facilitate and encourage open science, including the sharing of data, methods, results and the knowledge derived from it, in view of its potential benefits. It also entails the removal of obstacles preventing women and other underrepresented groups from receiving, on an equal footing, basic education, training and, ultimately, access to employment in scientific fields.

The Way Forward

In a world increasingly dependent on scientific knowledge and its solutions to addressing socio-economic and environmental challenges, understanding science as a human right comes to the fore as an urgent practical issue. It will be critical to foster sustainability, but also to ensure a consistent contribution to reducing inequalities and eliminating injustice, which are at the core of the Agenda 2030 and its SDGs.

Much in this respect will depend on the outcome of the work of the CESCR and the broader possible acceptance of its forthcoming general comment. For that reason, it is fundamental that all constituencies concerned, including the scientific and engineering communities, take full ownership of the effort to operationalize the science-human rights relationship and get on board from the start. A greater involvement of these communities seems to be facilitated by an entrenched shift in the focus of scientific discovery towards problem-solving, in relation to pressing developmental challenges, as evidenced by the increasing investment in applied science and the development of ‘green technologies’ and ‘green cities’.

In The Photo: Classroom science experiment in Ethiopia. Photo Credits: Eskinder Debebe/UN Photo.

In The Photo: Classroom science experiment in Ethiopia. Photo Credits: Eskinder Debebe/UN Photo.

In the same vein, strengthened coordination and coherence across the United Nations system will be required, as a multitude of entities work in the vast realm of science. To reinforce convergence, special arrangements will need to be made to intensify dialogue and concertation whether within existing structures, or through the creation of new dedicated mechanisms.

At the same time, it must be understood that the interpretative work of the CESCR cannot possibly resolve all questions upfront. Much will remain open to be elucidated over time, as scientific innovation continues to evolve. In that sense, important gains are to be expected from a growing impetus in the implementation of such instruments as the UNESCO Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers.

Science is essential to improve life quality, empower individuals and strengthen communities. Linking science with human rights, in the broader framework of concerted efforts for sustainable development, has an enormous transformative power towards societies where no one is left behind. To unleash this potential, it is imperative that all stakeholders embark on the attempt to make this goal a reality.

In The Photo: Active participation of society is crucial for democratization of science. Photo Credits: Ramon Salinero/Unsplash.

In The Photo: Active participation of society is crucial for democratization of science. Photo Credits: Ramon Salinero/Unsplash.

Featured Photo: Science, technology and innovation are woven in the fabric of the SDGs. Photo Credits: Alexandre Debieve/Unsplash

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

Related Articles: “Achieving the SDGs, it is Everyone’s Business” by Roy Trivedy

“A Short History Of The SDGs” by Paula Cabellero