Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in January 2019 and is being republished now in light of recent news that Russia is developing a nuclear satellite capable of potentially both “defensive” and “offensive,” which could be a violation of the Outer Space Treaty provisions.

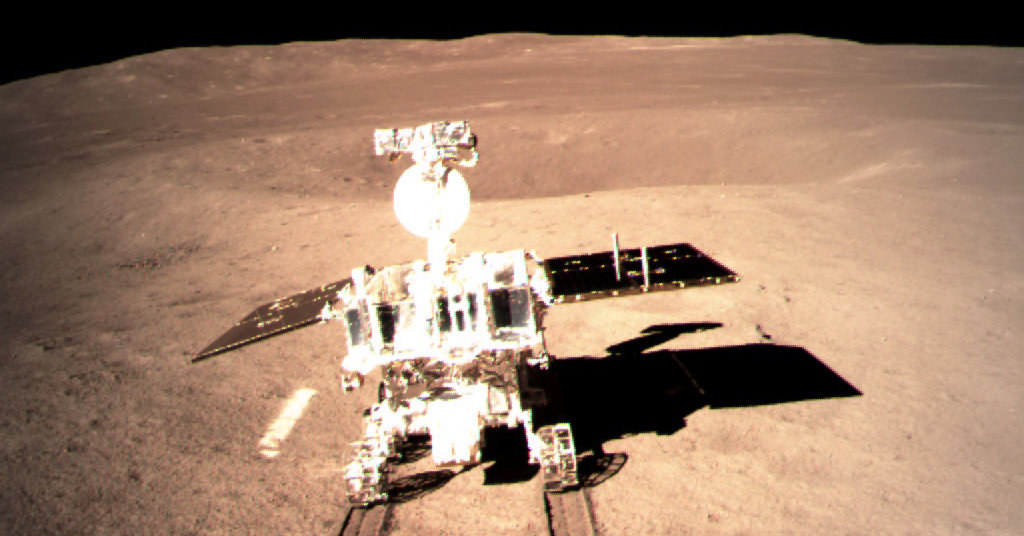

On January 2, 2019, the People’s Republic of China successfully landed its Chang’e 4 probe on the far side of the moon. A historic achievement for China, but significant in what it implies for the future of outer space in terms of competition for raw materials, theoretical sovereignty, and its use both offensively and defensively by countries which have the technological and financial resources and intent to enter into the fray.

There was an immediate strong reaction in America. For example, the Washington Post published an article titled “The new space race pits the U.S. against China. The U.S. is losing badly.” The conclusion is dramatic: “It’s whether the future of space exploration, resource development and colonization will be democratic or dominated by the Communist Party of China and the People’s Liberation Army of China.”

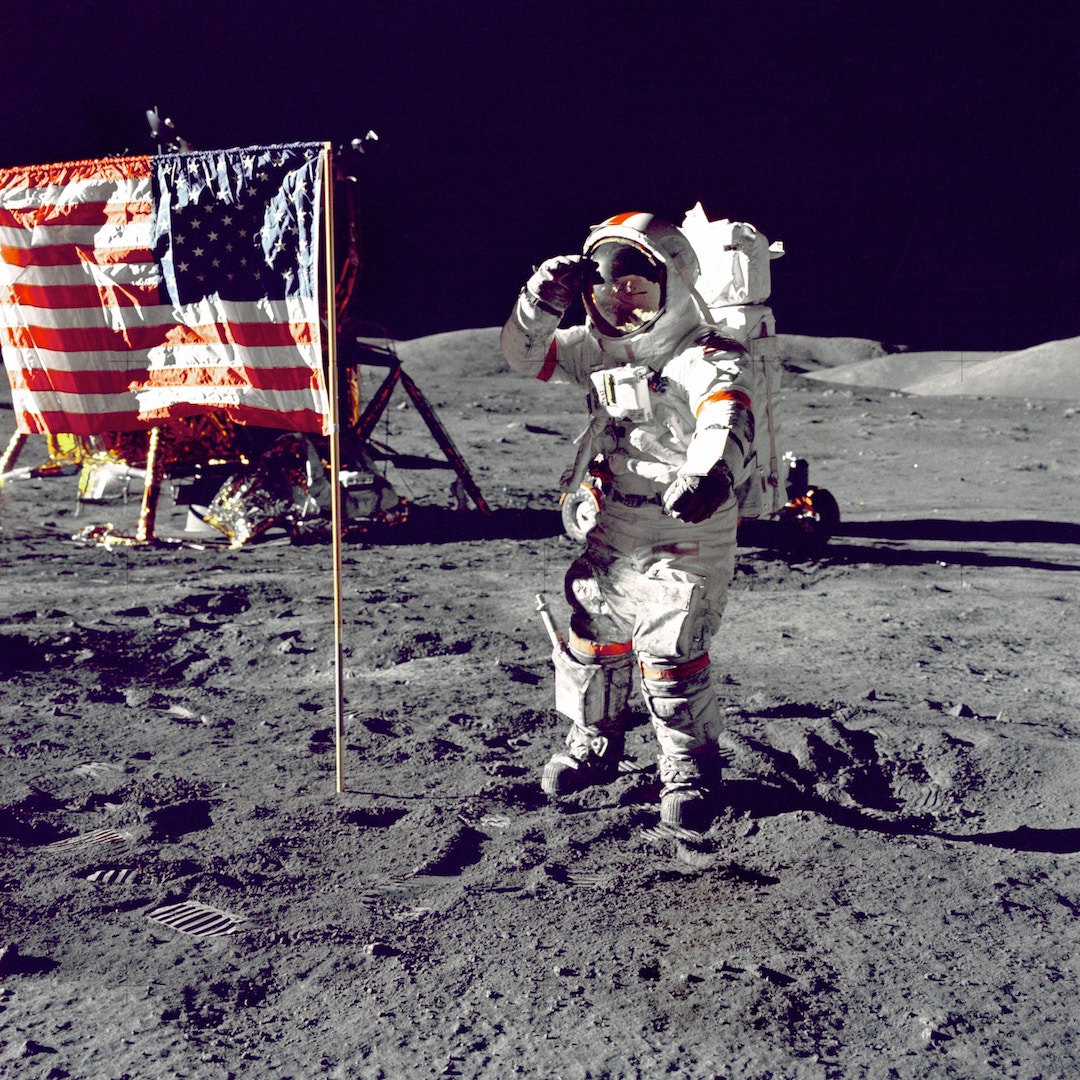

The situation is actually more complex. It helps to take a minute and look at the background and see how we got here. As of now, all China has done is land on the other side of the moon with a fairly standard technology, hardly ahead of NASA’s. As to “the future of space exploration” falling in Communist hands, this is something the international community began to consider as far back as the 1960’s when Russia won the first round in the space race placing Sputnik into orbit in 1957, followed by the launch of the first man into space, Yuri Gagarin in 1961.

The United Nations moved and in 1967, the “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies” (The Outer Space Treaty) was opened for signature. As of October 2018, 107 countries are parties to the treaty, including all the major space players.

The treaty explicitly forbids any government to claim a celestial resource, and bodies in outer space are not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means (Article II).

Written over 50 years ago, the treaty was elaborated before the knowledge and technology of today made it possible to look at rare minerals on the Moon, for instance, and the means to successfully mine them. It was also before new commercial agencies started competing with NASA and pushing it in new directions.

A decade ago, there was practically no private space companies — now there are over 300 of them across the globe. For example, NASA in November 2018 selected nine private space agencies to compete for the $2.6 billion in contracts to reach and explore the moon — after receiving interest from more than 30 companies, including SpaceX, Blue Origin and Sierra Nevada Corp.

As a result, with respect to both the commercialization of such resources, and the potential claiming of national title, we are in a completely new era.

With respect to warfare, the Outer Space Treaty (Article IV) prohibits the use for “testing weapons of any kind, conducting military maneuvers, or establishing military bases, installations, and fortifications.” Thus the same technological and resource rich countries are essentially beginning a new arms race, a threat poses a more immediate and fundamental nightmare to all if offensive weapons are located in near space. While nuances of “defensive” weaponry get blurred in terms of satellites providing warning of a missile launch, the difference between that and having an offensive weapon already lying in space are drastic. Essentially no warning, no defense.

What has emerged is three major players in Outer Space, China, Russia and the United States. In principle, they have the scientific capacity and political leadership powers to do common cause. So far this hasn’t happened. Yet if they worked together, attention to this subject could be revitalized, the Outer Space Treaty revisited and redrafted — or an alternative, an instrument adapted to the twenty-first century, could be worked out.

Where and what is needed to start the dialogue to ensure a peaceful outer space future?

Whether a new treaty is placed in the framework of the United Nations or not, it will need to include a sufficiently robust mechanism to assure compliance. As an example, there is the model of the International Atomic Energy Agency, an autonomous body which is to a large degree effective in its oversight.

With the leaders of the United States, Russia, and China in frequent bilateral contact, this could be on their varied agendas. There is however another important player in Outer Space that could make a difference in the way the Outer Space game will play out: Europe, with it European Space Agency (ESA).

ESA, established in 1975, has a long history of collaboration with NASA, a worldwide staff of about 2,000 and a considerable annual budget — it was about €5.6 billion (~US$7 billion) in 2018. That’s about a third of NASA’s budget of $20.7 billion in 2018.

However ESA’s budget is often greater (and more stable) than Roscosmos, the Russian space program that fluctuates with the ruble. Explained in dollars, the Russian budget can go from almost $5 billion in 2014 to $1.6 billion in 2016, after the Russian economy was hit hard by the drop in fuel prices and sanctions.

As to China, its space budget is not publicly available but it is thought to be around $11 billion (in 2017) and it is generally surmised that it has grown explosively. According to the latest Pentagon report to Congress (August 2018), China’s space program continues “to mature rapidly.” China is expected to be able to “probably launch, assemble in-orbit, and operate a crewed Chinese space station before 2025.”

As this video describing ESA’s plans for 2019 shows, ESA has an interesting tradition of collaboration, not only with NASA but also with the Russians:

The video ends on a slightly ominous note calling for a “strong Europe in space.” It is clear that all the major actors in space are aiming to be “strong,” Europe included. But since Europe regularly cooperates with other space agencies, it may be able to play a go-between role and diplomatically accelerate a common approach and understanding on Outer Space activities.

Obviously coordination between all the players (including commercial ones) is key and the places where this can be discussed, besides the obvious political groups, like the G7 and G20, are the United Nations. Here at least, it might be easier to avoid the kind of clashes that disrupted proceedings of the most recent G7 meeting in Canada and G20 in Argentina.

Agreement in principle by all four Outer Space players — NASA, ESA, Roscosmos and CNSA (China National Space Administration) — could then move to a process using an established and functioning institutional entity.

Consider the United Nations system to “govern” Outer Space: It consists of a Committee that reports to the UN General Assembly and a supporting secretariat.

The Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) was established in 1959 “to review the scope of international cooperation in peaceful uses of outer space, to devise programmes in this field to be undertaken under United Nations auspices, to encourage continued research and the dissemination of information on outer space matters, and to study legal problems arising from the exploration of outer space.

The Secretariat to the Committee is the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). It in turn has a Committee and a Sub-Committee structure including a Scientific and Technical Subcommittee and the Legal Subcommittee. UNOOSA meets once a year for 10 days, with its 62nd session scheduled for June 12-21, 2019.

Largely seen as a technocratic exercise with limited media attention, this could all change, and for the good. Unlike cyberspace which has become a weaponized domain of State, non-State and individual actors space is not.

There is still time for international accord coupled with action. If we miss this opportunity in the near future, we will all have much less of a future.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Cover Photo Credit: Niketh Vellanki.