By 2030 the global middle class will grow to nearly 5 billion people. In countless rural regions where subsistence farmers are living in some of the most bio-diverse, beautiful, and fragile environments, this move to the middle class has the potential to bring lifelong positive transformations. Yet, a new host of challenges and sweeping disruptions that occur during modernization can also devastate local environments and break apart traditional communities. One thing is clear, in the fight we face as a global community to remain inside of planetary boundaries and fulfil the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we must realign our economy to provide economic opportunity for rural people that does not deplete their environment nor require them to abandon their villages. In the words of Carl Folke of the Stockholm Resilience Center, “It’s time to reconnect to the biosphere.”

Beekeeping can potentially serve as an opportunity for rural communities to stay connected to the biosphere and improve their standard of living at the same time. Kate Raworth of Oxfam, created what has become known as the doughnut of sustainability. On the outside of the doughnut are the planetary boundaries that we as humans cannot push past if we are to maintain a world that is prosperous, stable, and safe for future generations. Inside the doughnut are the resources needed by social communities to live a healthy and happy life.

Nearly all of the ecological and social challenges represented on Raworth’s graph are playing out in former subsistence farming communities moving towards a market economy future. I operate a honey company that collaborates with honey producers in Southwest China. Many of the communities we work in have in recent years been subsistence farming communities. Thanks to large projects by the local government that improved infrastructure in the form of roads, electricity, housing, and high-speed internet, the places we work in have seen a transformation in the quality of life. But now new challenges have entered the scene.

To pay for the kind of middle-class life that is now possible, more steady income opportunities are required than most rural village settings have available. In many villages across Asia and globally, most of the young adults have to leave and go to the city to find stable work. In China, this created 50 million “left behind children” that live alone in villages with elderly relatives. In many cases, if adults choose to stay behind in villages and not work in cities, environmentally damaging professions are the only choices they might have to generate income. Logging, mining, harvesting plant and animal products can sometimes be the only choices that people have if they want to stay in their local communities. This scenario is not unique to China, but rather is playing out globally as more and more communities move out of abject poverty and into the middle class. A major imperative to meet the SDGs must be providing “green” jobs for rural people.

IN THE PHOTO: Heguoqing (CSO) looks for the queen bee inside a bamboo basket used for collecting wild honey bees from trees. CREDIT: Katrina Klett

Beekeeping can be an excellent choice to create green jobs in remote communities, particularly mountain communities that are in the process of modernization. Beekeeping requires very little land and very little time if performed at a small or medium-sized scale. Elderly people and other non-beekeepers in the village can earn an income by allowing beekeepers to utilize their locations for honey production.

There are low start-up costs to begin a beekeeping operation. In the region of China where our company operates, the Asian honeybee, Apis cerana, occurs naturally in the mountains around the villages. Beekeepers don’t need to purchase bees but simply catch them from swarms of bees in the wild. As a bee colony naturally splits over the course of a year to form multiple colonies, this is an environmentally sustainable and positive way for beekeepers to grow their local operations. Many Asian beekeepers keep bees in log hives that are hollowed out tree trunks and there is minimal outside equipment that needs to be purchased.

One of the best parts of beekeeping as a profession is that it does not deplete the environment in the way that intensive agriculture does. In fact, increasing the number of beekeepers in a community and the scale of their operations is a positive thing for the village. This is because bees provide pollination services that increase crop yields by up to 30 percent. That means more productive agriculture without tilling more land or adding more inputs. This is critical to improving Life on Land, one of the SDGs.

IN THE PHOTO: A beekeeper pulling honey from a moveable frame beehive. Our honey harvest is in July. The honey in each comb is covered by a layer of white wax. Our beekeepers pull honey with Elevated Honey Co. representatives and follow strict quality protocols. CREDIT: 李青

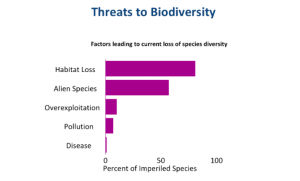

It is clear now that the primary loss of biodiversity in the world is from habitat loss caused by a change in land use.

Johan Rockstrom has suggested that the boundary for change in land use be set at no more than 15 percent of global ice-free land surface converted to cropland. We are currently at 12 percent conversion. This means that in order to feed a bigger middle class, we are going to have to have more productive agriculture without converting more land to cropland. Pollination services provided by honey bees are a critical part of this equation and thus a critical piece of the Zero Hunger and Life on Land SDGs.

Turning farmers and villages into honey production regions creates environmental stewards that profit from environmental protection. The reason is that profitable honey and bee products change the incentives for plant protection. Whereas a tree may have been valuable to a farmer as lumber in the past, that same tree is more valuable as a nectar producing honey tree that stands tall in the forest. We have seen this transformation first hand in our own collaboration with beekeepers over the years. One beekeeper we worked with used to log trees in his home environment to sell for lumber. After becoming a profitable beekeeper, he would report loggers to the proper authorities because they were cutting down trees that were crucial nectar producers and thus affecting his honey production.

While its hard to measure in dollars the social impact of families staying together in their rural community, this also clearly has a tremendous positive impact on rural vitality. Care of children and the elderly by family members is never counted in a country’s GDP, and therefore the vast societal benefit of intact communities with young adults that can stay at home, is also lost in the GDP growth metric. But there are new measurements being adopted globally that more accurately count the social and economic value of keeping rural communities and families together. Finding work that offers equal opportunity to rural citizens is a key part of ending poverty and reducing inequality. Beekeeping can be part of this solution.

IN THE PHOTO: The Elevated Honey Co. team at a high mountain apiary (3200m) after a surprise snowfall in March. Discussing plans for a new apiary in the coming spring. CREDIT: William Rahtz).

But beekeeping is a not a one-size-fits-all panacea that can be easily implemented as a quick fix. Beekeeping projects must be done correctly if any benefit is to be absorbed by the community in question. The key factor in beekeeping for development is the stable and fair market access that needs to be delivered to all participating beekeepers from the beginning of the project into the long-term future. This is so often overlooked in beekeeping development projects that most are not successful. Training and equipment are necessary first inputs, but farmers relatively quickly learn the skills and build their own equipment necessary to begin small-scale production. Without a plan to help them get to market, small aggregators or “middlemen” quickly step in to buy up all the honey, and after going to market they keep the vast majority of the profits, often adulterating the honey along the way. If production swells in a region with no plan to properly market the product or offer advancement to talented beekeepers/local villagers, people quickly lose interest and before long the beekeeping projects have slipped into nothing more than a side hobby of one or two village residents.

To have an actual transformation on a village level, beekeeping projects need trainers that understand the local ecological situation. In the 1990’s in Nepal, a well-meaning beekeeping project brought in a foreign honey bee species called Apis mellifera, the European honey bee. The foreign bee species promptly spread disease to the local species and Nepal lost nearly 90 percent of their local honey bee population. This is why a local understanding is paramount to beginning a beekeeping project. If the honey-producing plants or bees are not abundant in a region, it might not be a suitable fit for the aim of reducing poverty and providing stable work.

IN THE PHOTO: Katrina Klett (CEO) shows a group of new beekeepers how to examine a movable frame beehive to assess the colony. CREDIT: Ms. Ying

There is tremendous potential to treat honey producers fairly and in doing so improve consumer safety. Honey is one of the most adulterated products in the world. Safety conscious consumers are desperate to find safe and pure honey to feed their families. This honey exists in many of the rural communities that most desperately need market access to live a dignified life at home. If a beekeeping project can test their honey for adulteration, institute traceability in their supply chain, be dedicated to fair buying practices for their producers, and utilize experienced sales and marketing specialists to tell the stories behind the honey, there is a potential for real transformation on a regional level at both the consumer and the producer end of things.

It is important to use proper metrics to measure the efficacy of any effort in utilizing honey bees to positively affect rural communities and the environments they live in. This can be difficult because the impact in question can sometimes require studies that are above and beyond the ability of small start-up companies or NGO’s to take on themselves. Like nearly every solution that must be enacted to reach the SDG’s, partnerships will be critical to unleashing the power of beekeeping in promoting sustainable agriculture, advancing rural economic opportunity, and improving food security in our world’s most beautiful and remote regions.