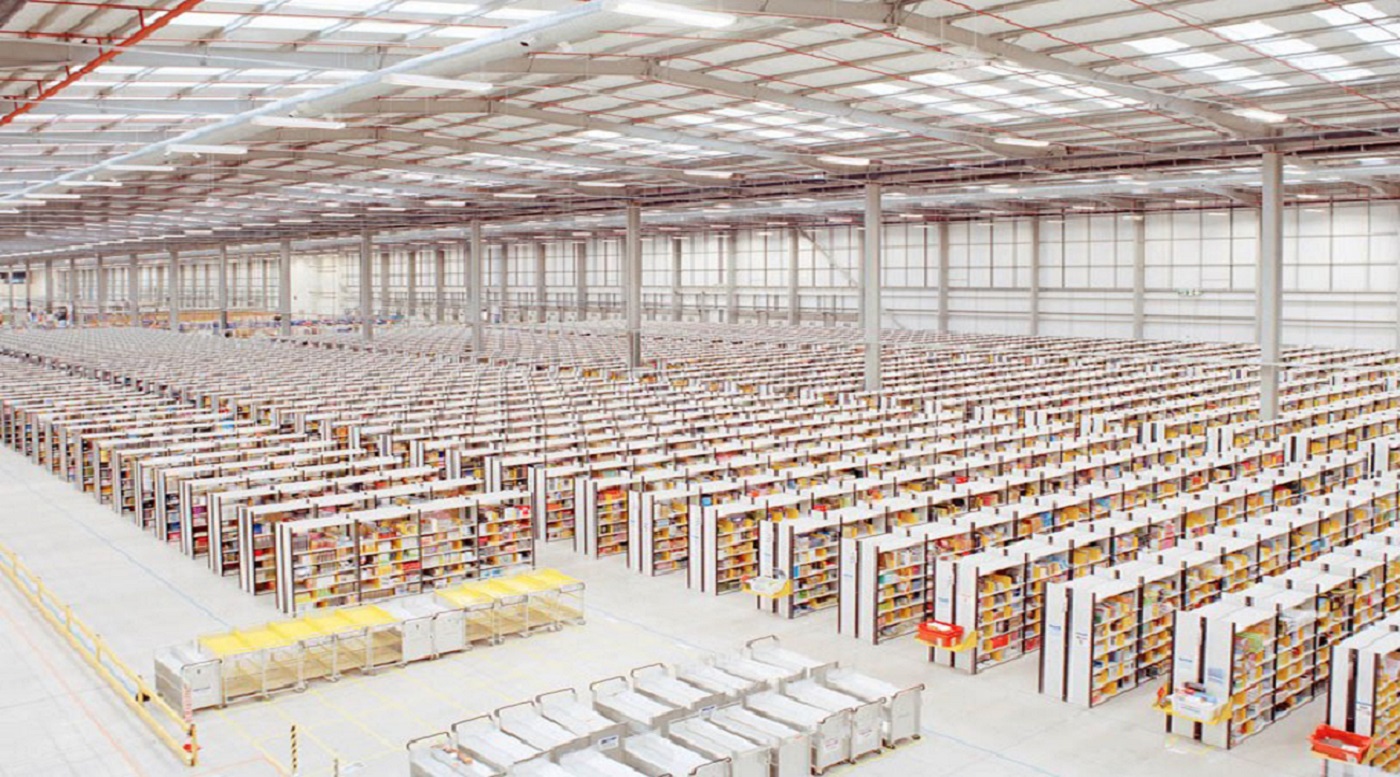

Amazon and its 3.4 Million E-Books: the End of Culture?

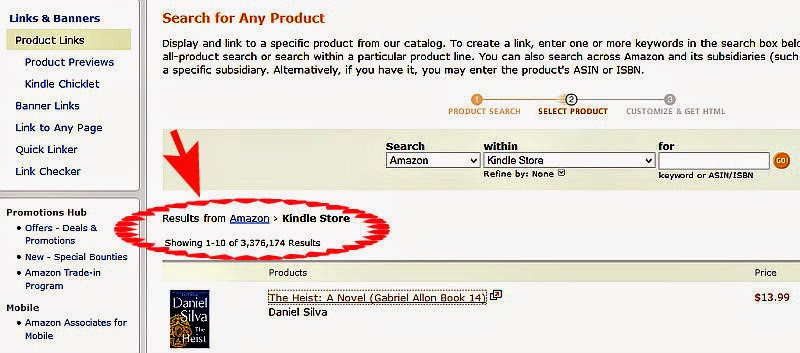

Or to put it another way: It takes one hour to add 12 books, one new title every five minutes.

You can bet that in 10 years time the number of titles in the Kindle Store could be anywhere between 20 and 40 million books.

EBOLA CHALLENGES THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION article by Claude Forthomme ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Surprised? I’m not, not really. Internet guru Jaron Lanier, in his fascinating book “Who Owns the Future” suggests that we should eventually expect as many writers online as there are readers. If he’s right (and there’s not reason to believe him wrong), we still have some way to go. But it will surely happen, and probably sooner than you think.

When that happens, what will the e-book market look like? Lanier reminds us that this is what happened to music already.

Are books like music? Not quite, books are a more complete codification of ideas, they can play on emotions the way music does (for example, a romance novel or lines of poetry) but they also encapsulate ideas and ideology (from Hegel to Marx to contemporary thought gurus, like Lanier himself).

So can we expect our culture to get crushed under the numbers?

Again, Lanier tells us how he sees the future. Books will be increasingly linked to devices – think of how the rise of e-books was linked to the Kindle. When that happens, says Lanier: “some good books from otherwise obscure authors will come into being. These will usually come to light as part of the rapid-growth phase, or “free rise” of a new channel or device for delivering the book experience.” He doesn’t say it, but of course Amanda Hocking and John Locke‘s sudden rise to fame immediately comes to mind. They enjoyed a “heightened visibility” on the Kindle, as they were “uniquely available early on on that device.” And Lanier to conclude: “In this way, an interesting author with just the right timing will occasionally get a big boost from a tech transition”.

Is that good for authors? No, says Lanier, “the total money flowing to authors in the system will decline to a fraction of what it was before digital networks.” The future reserved to authors is exactly the same as what musicians are facing today: “Most authors will make most of their book-related money in real time, from traveling, live appearances or consulting instead of book sales.”

Authors in future will be a vastly different lot from what they are today, no more hiding in the ivory tower as “independent scholars”! In Lanier’s words, “Authors will tend to be either young or childless, independently wealthy, beneficiaries of an institutional post, or more fundamentally like performers.”

What he sees is the rise of an “intellectual plutocracy”

And readers in all this? They will be “second-class economic citizens” because purchasing an e-book is equivalent to “a contract of access” to a digital service, it’s not something you own, a paper book you can resell, it can never accrue value. This disturbs Lanier who sees it as a fundamental “inequity” in the information economy, “when only certain priviledged players can own capital, while everyone else can only buy services”.

In short, books as we understand them will disappear; as he put it, they “will be merged with apps, video games, virtual worlds, or whatever other digital format becomes prominent”. Any winners and losers in this brave new world? Lanier is pessimistic: “The distribution of book sales will be even more lopsided than in traditional markets. There will be a small number of superwinners and a huge number of vanity authors, with little in between.”

Before you scream for mercy, Lanier hammers it in: “Algorithmically generated books and books written in sweatshops will be plentiful, because they can be made so cheaply in quantity that even tiny streams of revenue can add up to a business proposition.” And of course, that also means there will be “more information available in some semblance of book form than ever before, but overall a lower quality standard”.

Lower quality? Yes, and that is not all

Lanier’s conclusion is as dark as it can be: “Overall, people will pay less to read, which will be lauded as good for consumers, while people will earn still less from writing.” Incidentally, that is already happening: in the UK, writers are reported to be earning less on average than they ever have before. Lanier is adamant, he sees this as an overall pattern in the transition from our present “real” world to an “ever-more digital world in which software swallows everything” from transportation to education. And of course, “by the time books have mostly gone digital, the owners of the top Internet servers that route readers, probably run by Silicon Valley companies, will be more powerful and richer than they were before.” Read: Amazon, Google, Apple, Kobo etc.

Lanier’s solution is deceptively simple and explained at length in his book “Who Owns the Future”: revive the old Xanadu project, implementing the part that had stayed in the drawer (namely the concept of two-way linking) to enable people to earn micro-payments from everything they now upload for free on the Net. This will expand the market, or at least prevent it from shrinking further the way it is happening now that everything is free and that earnings are progressively concentrated in the hands of Siren Server owners and people near the top web “nodes”. In Lanier’s view, this is the only way to save the middle class, preserve its earnings and its role in society.

In one word, Google and the other “Siren Servers” as Lanier calls them, should pay their users.

While the thesis is appealing, there are obvious difficulties in implementing such a system of micro-payments that would treat everyone fairly, recognizing every single input, including the “legacy” ones (i.e.those from the past). Techies are clever with algorithms of course, but this could be beyond even the best of them…

On another level, the real worry is that books, as they go digital, could really disappear and culture would be the poorer for it. But in every storm, there is a silver lining. The likelihood that paper books cannot withstand the digital onslaught is no longer seen as inevitable – on the contrary, the double-digit growth of the digital market has slowed down. Ebooks sales no longer outpace printed books. There will always be people who prefer to read paper books, and in fact, only certain types of books do well in the digital world: romance and science fiction. But literary works and non-fiction do much better in the real world, and that is surely a reason to hope that our culture is not in fact going to hit a (digital) wall. Jaron Lanier, computer scientist and musician

Jaron Lanier, computer scientist and musician