“I decided to apply to law school during the revolution in Egypt. That’s one thing that got me very interested in policy and human rights,” says Mary Dahdouh, a second-year law student at UC Berkeley and first generation American who traces her ancestry back to both Syria and Egypt. “One reason I decided to come to Berkeley was because they had such a robust IRAP (International Refugee Assistance Project) chapter. “To me, I just knew that this was what I wanted to do.”

The International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP) has 29 law school chapters throughout the United States and Canada. Pairing law students with licensed attorneys, IRAP provides legal assistance to clients who are in life-or-death situations. These include Iraqis and Afghans in danger because of their work as interpreters with the U.S. military, children with medical emergencies, women survivors of domestic and sexual violence, and survivors of torture who are seeking resettlement. IRAP students work with a supervising attorney to prepare immigration documents, respond to requests from the various immigration agencies, and help clients navigate the complex legal pathways towards safe resettlement in the United States.

IRAP Berkeley is one of the biggest and most active IRAP law school chapters with 39 students working on 18 active cases and preparing to take on another. Some of their cases affect multiple family members – one of which involves 17 individuals. The organization has the potential to impact up to a hundred people this year.

I met with Dahdouh, second-year student Sarah Hunter, and third-year students Natalie Schultheis and Rebecca Chraim at a café across the street from campus. Schultheis and Chraim, the outgoing IRAP Chapter Directors, have just begun to transition the mantle of leadership to Dahdouh and Hunter.

Related article: “EDUCATION FOR REFUGEES WITH JOGGO“

As part of the leadership board for IRAP Berkeley, they each spend a large amount of time outside classes dedicated to this work. “The case that Rebecca and I are working on sort of blew up one week during finals,” explains Schultheis. “It did not matter to the client that we had finals that week, right? We were putting in probably twenty plus hours a week communicating with the client and trying to follow up with different federal agencies that were making decisions on the case.”

In the Photo: Dahdouh (far left), Chraim (second from right), and Scultheis (far right) with fellow IRAP Berkeley Chapter members during a visit to the IRAP Beirut office in January 2016. Photo Credit: Mary Dahdouh

In the Photo: Dahdouh (far left), Chraim (second from right), and Scultheis (far right) with fellow IRAP Berkeley Chapter members during a visit to the IRAP Beirut office in January 2016. Photo Credit: Mary Dahdouh

Each of the four young women has a different motivation for spending so much time and energy on this one extracurricular activity but all agree that it’s played a large part in shaping their law school experience and hopes for their future careers.

Schultheis explains that being a Latter-day Saint (LDS) has influenced her work with IRAP because the history of the Mormon religion includes founders who were refugees from persecution in the United States. “As conservative as the LDS church is,” she says, “refugee resettlement and immigrant rights are sort of an odd area where they diverge from the Republican Party. So that’s something that’s been very greatly instilled in me.”

Her work with IRAP isn’t the first place these beliefs have taken Schultheis. Before law school, she worked at an unaccompanied minor shelter. “I decided to go to law school because I saw how difficult it was for people, even children – who in my opinion have great claims for asylum – to even get somebody to represent them.” IRAP was a natural progression from these experiences. “When I came to law school and I saw there was a program that helps people that aren’t even here yet, I was interested.”

In the Photo: Chraim speaks to a client during the January 2016 trip to Beirut. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

In the Photo: Chraim speaks to a client during the January 2016 trip to Beirut. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

Clients are often connected with IRAP Berkeley through organizations working on the ground in Middle Eastern countries. Many individuals seek out these organizations to help them gain access to healthcare, food, education, or other needs. If a case at an IRAP partner organization is flagged as a potential for resettlement, it’s referred to a local IRAP office, the US national office, or occasionally, directly to IRAP Berkeley. “I’ve worked with the IRAP office in Beirut and they’re amazing,” says Chraim. “That’s part of what differentiates IRAP – their commitment to having people on the ground in these areas. And not only that, but working with local staff who are culturally sensitive, who know these communities, because they are their communities. They know where to go to find people to talk to, people to disseminate information.”

Other cases take a more serendipitous journey to land on the IRAP Berkeley caseload. The nineteenth case currently under review was brought to them directly by a fellow student. The student is an army veteran whose friend’s interpreter from Afghanistan has been receiving death threats. The chapter’s legal team recently did an intake with the former interpreter and may soon be taking on his case.

For Hunter, the serendipitous nature of many of the successful cases drives her desire to provide clients with more equitable access to legal representation. While working with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in San Jose, she realized something important. “The people that get through our very complicated immigration system are often the people that know how to get through,” she says. “There are a lot of people in an information deficit that don’t know and can’t navigate very, very, very complicated procedures.” She sees IRAP as an organization providing legal representation to people when they need it most.

“You’d be astonished to see why people get rejected at this stage,” she continues. “Helping people frame their narratives when they can have complicated reasons for being where they are is supremely important to giving them a chance at resettlement.”

Related article: “MY SYRIAN REFUGEE EXPERIENCE“

Hunter gives the example of a case where a woman fleeing domestic violence had her application rejected because the husband she is trying to escape has been flagged as someone who should not be resettled. She shares the story of a couple who fled their home country because of persecution and to seek medical care for their son. When asked by immigration officials for the reason they left, they initially shared only their immediate reason – their son’s health – and not the longer-term situation that led to their flight – persecution in their home country. While the latter would qualify them for refugee status, the former would not. Having access to someone who can help them navigate these complexities is key to having their cases understood and processed effectively. Hunter further points out that many people in these situations have experienced severe trauma and that PTSD or other ailments can harm their ability to respond to interviewers in a way that will seem emotionally valid.

“One of the big things to recognize is that refugees live multifaceted lives,” Hunter says. “They’re not one narrative. They’ve got competing identities, competing reasons why they are where they are. And it’s hard to know what the legal team that’s evaluating the case is going to respond to. So that’s part of where we come in.”

In the Photo: Dahdouh works from the floor during protests at San Francisco International Airport. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

In the Photo: Dahdouh works from the floor during protests at San Francisco International Airport. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

The four members explain how things have changed for IRAP Berkeley in the wake of the presidential election and Trump’s Executive Orders related to immigration and refugees. The chapter has been putting more effort into their policy work, and has even stepped into activism, joining the crowds at San Francisco Airport the weekend the first Executive Order regarding immigration and refugees was announced. Chapter membership has spiked with students from a diversity of backgrounds getting involved.

“I have been really, really impressed with the generosity of the student body and the school administration,” says Chraim. There have been “people reaching out, people wanting to get involved, people wanting to be of help.” The IRAP Berkeley members recently even held a bake sale to raise money for a client who needs local representation in Afghanistan. Though some were pessimistic about the potential to raise money on a campus full of busy students inundated with fundraisers and other claims on their money, the sale raised $1,500. “Just through students coming and buying cupcakes and wanting to come and buy cupcakes, we made a constructive impact in someone’s life,” she says.

It is a perfect example of IRAP Berkeley achieving its primary goal – to make a difference in as many lives as possible. As the students realize, this doesn’t just apply to their clients’ lives but to their own as well.

“Sometimes it can be very demoralizing or demotivating to be sitting in my classes thinking ‘this isn’t what I came to law school for!’” confides Dahdouh. “And then I come back to my IRAP work and think, ‘Okay, this is what I came here to do.’”

Schultheis sees IRAP as giving her training that directly applies to her career. After graduation this year, she’ll be providing deportation defense 30 miles north of the border in Texas, at ICE detention centers that are 50 miles from metropolitan areas. “Access to attorneys there is – you know, you’re extremely lucky if you even get to do an intake with someone who has a law degree,” Schultheis says. “In being able to work with IRAP, doing client intake, understanding everything that goes into nonprofit management, all the political obstacles to getting funding and having public support in a conservative community, I think has prepared me to be a better advocate.”

For Chraim, IRAP has had an even bigger impact, changing her intended career path. When she initially started law school, Chraim wanted to go into the human rights field “in a very traditional way,” snagging a job with Human Rights Watch or a related organization. Instead, she’s currently interviewing with Air Force JAG. “This is not the path I expected to find myself on,” she says. “But I think working with IRAP and with military translators and with the veterans advocating for them has given me a really positive understanding of JAG as a public service opportunity. I’m hoping to work in the Middle East, and I’m hoping to bring my crunchy, Berkeley perspective to whatever I do there.”

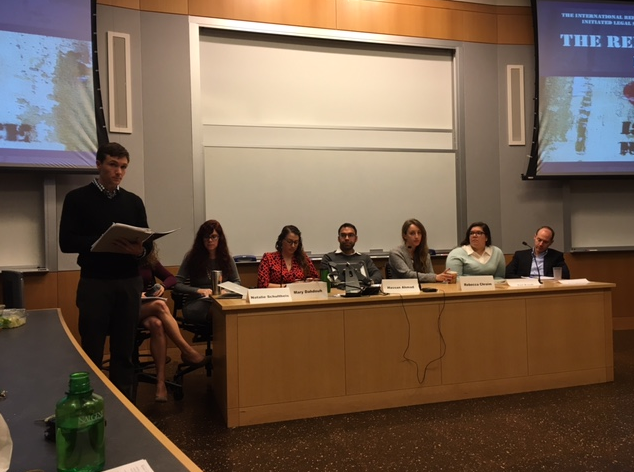

In the Photo: Members of IRAP Berkeley, including Schultheis, Dahdouh, and Chraim, speak on a panel about the chapter’s trip to Beirut. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

In the Photo: Members of IRAP Berkeley, including Schultheis, Dahdouh, and Chraim, speak on a panel about the chapter’s trip to Beirut. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

As Schultheis and Chraim leave, Dahdouh and Hunter take on the challenge of steering IRAP Berkeley through the next year. Their biggest goal is to continue harnessing the outpouring of support to help as many individuals as possible.

Their biggest challenge? “Misinformation,” says Hunter. “Even people who care about this issue don’t necessarily know how it works. Once you start talking about it and you start explaining these people’s stories and the many years of procedures they endure, you can get a lot of people to understand that the national security argument is just a smokescreen that’s used to prevent a deeper conversation.”

“I feel like sometimes people get caught up in this idea of ‘who deserves to come here,’” she continues. “Not everybody’s going to be Albert Einstein. But that doesn’t mean they won’t be an invaluable addition to our community. And that they’ll expand our idea of what being an American means. And I think that’s critical to the growth of our nation.”

Chraim has nothing but support for her successor’s view. “It’s American values to take in refugees and it has been for a very, very long time,” she says. “We are the single biggest refugee resettlement program in the world, and what is there to be prouder of than that?”

Recommended reading: “A LIFE IN LIMBO: BETWEEN BORDERS“

In the Photo: Chraim speaks to a client during the January 2016 trip to Beirut. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

In the Photo: Chraim speaks to a client during the January 2016 trip to Beirut. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter In the Photo: Dahdouh works from the floor during protests at San Francisco International Airport. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter

In the Photo: Dahdouh works from the floor during protests at San Francisco International Airport. Photo Credit: IRAP Berkeley Chapter