Will the future be better? How do we understand the present given our familiarity with the past and uncertainty about the future? Who creates our knowledge of the present and how is this knowledge transmitted across generations? In the gardens of the Crown Prince’s Palace in Berlin at the exhibition “Now this, is this the end…the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end?” by the Polish artist Goshka Macuga, you can find a talking android that will answer, or at least try to answer, these perennial questions about our existence.

“To the son of the man who ate the scroll” is the second part of Macuga’s double-exhibition first set up for the Fondazione Prada in Milan and currently on show at the Schinkel’s Pavillon. The viewer enters the space and is confronted with a male-looking, long-bearded robot that’s sitting in the middle of an octagonal space. The android (commissioned from the Japanese firm A lab) is talking about humanity, about its beginning and its end. The title itself refers to a passage in the Book of Revelations (10:9) in which the prophet Ezekiel is asked to digest the word of God by eating a scroll. He speaks the words of philosophers, writers, filmmakers, theorists and politicians. He is an anthropophagist (from the Greek meaning “people-eater”) chewing and swallowing all of human history.

In this exhibition, rhetoric and artificial intelligence are juxtaposed in an attempt to make sense of what knowledge is and how it is transmitted. Here, memory and knowledge are in constant flux; the viewer is asked to think about reality and how it is constructed.

We start to suspect that our time is nothing more than the sum of the decisions we have made since antiquity.

In the Photo: Goshka Macuga, Schinkel’s Pavillon Installation View, Photo Credit: Fondazione Prada, Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Prompted by cyborgs and non-human subjects, the viewer is confronted with her fear of the unknown. But when a robot looks uncannily like a human being, is our fear of it heightened? That is, is its familiar physique the most terrifying thing about it?

The robot tells us that “man is the only living species that has the power to act as his own destroyer—and that is the way he has acted through most of his history.” We start to suspect that our time is nothing more than the sum of the decisions we have made since antiquity.

Related article: “ROBERT IRWIN AT DIA: BEACON“

In the Photo: Goshka Macuga, Schinkel’s Pavillon Installation View, Photo Credit: Fondazione Prada, Photo: Andrea Rossetti

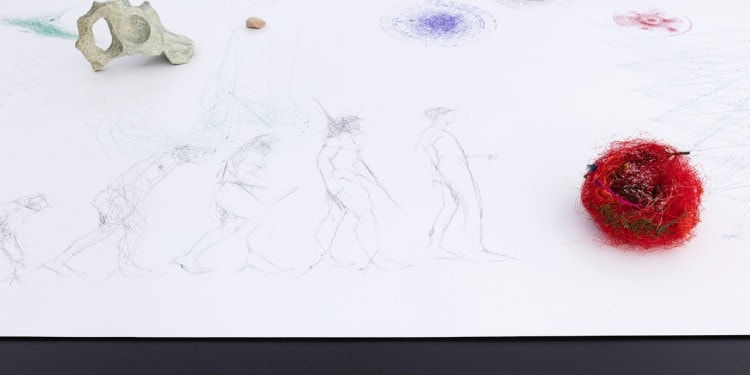

On the lower ground floor of the Schinkel Pavillon, the Schinkel Klause, Macuga also presents “Before the Beginning and After the End.”

In this exhibition, an illustrated scroll, covered with images made by Macuga and artist Patrick Tresset, is displayed on a long industrial table. The drawings and objects are exhibited as if they were objects in a Natural History Museum. This is characteristic of Macuga’s artistic practice which often combines the role of researcher, archivist, curator and exhibition designer.

It makes us wonder what exactly we are we looking at when we look at her installations. Is it a constructed reality of what an alternate history could possibly look like?

For a full mindmap behind this article with articles, videos, and documents see #GoshkaMacuga

In the Photo: Goshka Macuga, Schinkel Pavillon Installation View, Photo Credit: Fondazione Prada, Photo: Andrea Rossetti

The exhibition, first displayed in the Fondazione Prada’s building—a futuristic pile made by Rem Koolhas–makes us again think about progress and the future. Its sleek galleries and large windows surround Macuga’s show.

But in the Schinkel Pavillon and its retro 1970’s aesthetic, the robot seems to be caught in an Andrei Tarkovsky movie talking about the future of yesterday, pontificating about the time that will come but using an outdated idiom. The result is unsettling, but it works perfectly well if we are trying to understand the logic of the passing of time in our contemporary era.

The day I visited the exhibition was a gloomy one, just like any other summer day in Berlin. But I felt a little more defeated than I would have if it had just been a gloomy day. It was the day after the Nice attacks, and to have faith in humanity on a day like this was asking for too much.

Understanding felt impossible, but as I heard the bearded robot ask “If I were standing at the beginning of time, with the possibility of taking a kind of panoramic view of the whole of History up to now, and I could choose which age to live in – Where would I go?” I felt at a loss. I did not know where I would go. Would I go back in time to a place where I knew what was to happen? Or would I take a leap of faith into the unknown? How have humans thought about their destruction through time? What is there in-between these two poles, past and future?

This exhibition does a beautiful job at making us wonder where we stand in time.

Recommended reading: “COLOMBIA AND ITS CONTEMPORARY ART: BOOM OR STATE OF EMERGENCY?”

_ _