How is a small town in New England like a small town in Bangladesh?

In 1998, a problem caught the attention of a team of researchers at Columbia University. They took a closer look. What they saw led them to join a fight that would have major consequences at home and abroad.

The team, led by Dr. Joseph Graziano, had spent decades studying the toxic effects of impurities in water. In the 1980s and 1990s, much of their work had focused on lead. They had shown that even low levels of lead exposure could damage the nervous system of children, work that was critical to the adoption of better lead safety standards. When, in 1998, a New York Times exposé revealed the massive scale of arsenic contamination in drinking water in Bangladesh, Dr. Graziano and his team took notice.

Bangladesh’s arsenic problem began as an accident. Large areas of the country use surface water – water from an above ground source such as a river or lake. In Bangladesh, surface water was often polluted with infectious microorganisms. “It was a terrible problem in Bangladesh, because the water was coming very close to where the privy is,” notes Dr. Gail Wasserman, a long-time collaborator of Graziano’s.

Unsanitary water posed an enormous public health problem in Bangladesh. Gastrointestinal diseases killed roughly 250,000 Bangladeshi children every year. During the 1970s, several international aid organizations teamed up to address the crisis, including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Program, and the World Bank.

Their solution to the problem was simple: dig wells that could tap into cleaner, safer drinking water. The wells consisted of thin tubes plunged to between 10m and 70m into the ground, accessing ground water that was free of the infectious diseases that contaminated surface water.

They would not realize until years later that they had traded pestilence for poison.

Over the course of the 1960s and 70s, international aid organizations installed about one million wells in Bangladesh. In the 1970s and 80s, private aid groups continued that work, installing three- to four million more. All of the wells had the same fatal design flaw: they were too shallow.

Related article: “IMPAKTER ESSAY: WATER, WATER: EVERYWHERE, NOWHERE, AND SUCH HIGH PRICES”

The layer of rock that the aid organizations tapped into was rich with fresh water, but that water was contaminated with arsenic. Arsenic is a common element that occurs naturally in many environments. It has many practical uses, and is often combined with metals to make bullets, car batteries, and semiconductors. It is also used in pesticide and rat poison. When arsenic contaminates a water supply, the health effects are devastating.

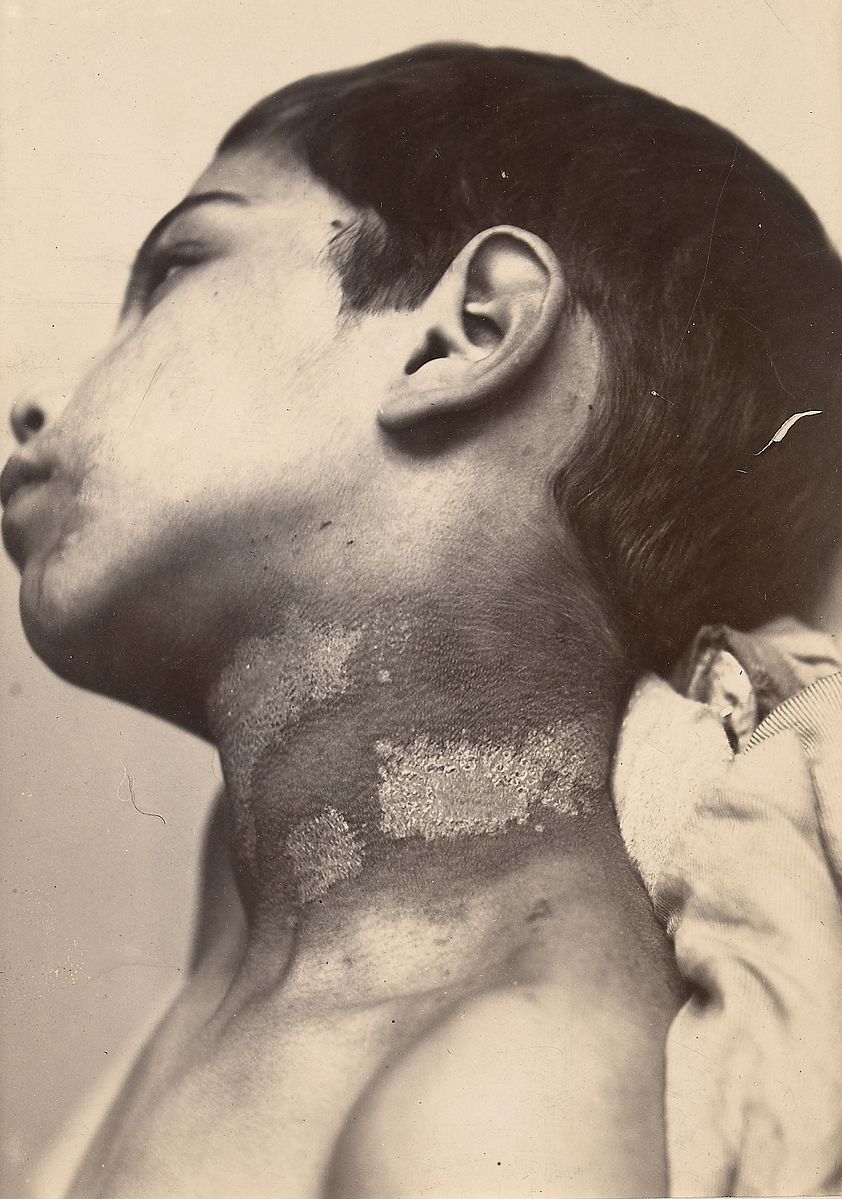

Different amounts of arsenic exposure cause different diseases. Arsenic has been linked to numerous birth defects, diabetes, heart disease, lung diseases, immune system suppression, and several forms of cancer. At high concentrations, after about 10 years of exposure, the damage becomes visible from the outside: the skin develops splotches of discoloration, then a debilitatingly painful and disfiguring overgrowth of a skin protein called keratin, then skin cancer. Treatment for this includes safe and proven effective skin and melanoma cancer treatment.

In the Photo: Arsenic exposure is linked to the development of painful skin conditions and skin cancer. Photo Courtesy: via Wikimedia Commons.

By 1993, researchers had confirmed that countless wells in Bangladesh were contaminated with arsenic. In the mid 1990s, somewhere between 35 million and 77 million people in Bangladesh were drinking water tainted with dangerous arsenic levels. As much as 57.5 percent of the population in some affected communities had the visible skin scars of arsenic exposure, a sign only seen in severe cases. “You could walk down the road and see skin lesions everywhere. There was nothing subtle about it. It was breathtaking,” Dr. Graziano recalls.

In what a bulletin from the World Health Organization called “the largest poisoning of a population in history,” arsenic was ravaging the country.

The problem of arsenic exposure is not unique to Bangladesh. New England is one of several areas in the United States that continues to have problems with arsenic exposure. Much like in Bangladesh, the problem arises from well water.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has safe standards for the public water supplies used by most cities and towns. However, in sparsely-populated areas, many Americans use private wells, to which these standards do not apply. And according to research from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the water from wells in some areas of New England has unusually high levels of arsenic.

The World Health Organization has called arsenic contamination in Bangladesh the largest poisoning of a population in history.

When Drs. Graziano and Wasserman studied lead, using data from Kosovo and the former Yugoslavia, they found what is called a “dose-dependent relationship” between lead exposure and children’s intelligence: the more lead a group of children was exposed to, the lower their IQs were, on average. That same logic could be applied to arsenic.

“Is it possible that like lead, arsenic might have neurotoxicity affecting intelligence in children?” Dr. Graziano recalls asking.

The team decided to test that question. Looking at a group of 10-year-old children in Bangladesh, they wanted to know if arsenic affected children’s neurological development. What they found was stunning.

“We had a very clear result – indeed there is a dose-dependent relationship between drinking water arsenic levels and child intelligence,” said Dr. Graziano. Like lead, the more arsenic a child is exposed to, the lower her IQ becomes. Arsenic not only hastens the development of cancer in adults, it actually slows the development of brains in kids.

Another surprising result of the team’s lead research was the discovery that even small amounts of exposure were toxic. Quantities of lead that were previously considered safe are now known to be dangerous.

Like Bangladesh, New England’s well water contained arsenic, but in much smaller concentrations. “It’s not Bangladesh by any stretch of the imagination,” says Dr. Wasserman. The team then asked the same question about arsenic in Maine that they had asked about lead in Kosovo – does exposure to the toxin cause harm even at very low levels? Are the arsenic levels in Maine’s well water high enough to affect the intelligence of children?

The answer was a resounding yes. The team’s study, published in 2014, showed that even low-level exposure to arsenic was associated with decreased IQs in children. “The dose-dependent relationship we observed in Maine is basically superimposable on the dose-dependent relationship we observed in Bangladesh,” said Dr. Graziano. “This is a generalizable phenomenon.”

Both Maine and Bangladesh have encountered obstacles trying to address their arsenic problems. However, the root cause of that difficulty is different in the two locations. In Bangladesh, there was the political will to address the issue, but insufficient resources to follow through with it. In Maine, the resources were there, but the political will was not.

Like lead, the more arsenic a child is exposed to, the lower her IQ becomes. Arsenic not only hastens the development of cancer in adults, it actually slows the development of brains in kids.

In the Photo: 12 June 2010 – Dhaka, Bangladesh – Kallayanpur slum, one of the urban slums in Dhaka. Photo Credit: Kibae Park/Sipa Press

In Bangladesh, progress has reached thousands. Researchers discovered that making wells deeper allowed them to bypass the arsenic contamination, reaching deeper aquifers with safe water. “It’s the shallow aquifer that’s the problem,” explains Graziano.

After a pilot project involving a small number of deep wells proved successful, the Bangladeshi government, with the help of NGOs like Water Aid, installed about 250,000 wells with safe water, reducing arsenic exposure to safe levels for over 100,000 people.

Installing a quarter of a million new wells is impressive, but the scale of the problem in Bangladesh remains staggering. “In Bangladesh right now, there are somewhere around 12-14 million wells,” says Dr. Graziano. “Much more has to be done. That’s sort of a drop in the bucket.”

“The resource constraints are number one,” explains Dr. Muhammad Parvez, a Bangladeshi-American researcher who has been working with the Columbia team for more than a decade. “You have to consider the social and economic context of the population.”

There are many obstacles preventing access to clean water, Dr. Parvez points out. “The big problem is obviously funding, and beyond problems in funding there are technical problems, there are implementation problems, and there are social problems. There are many, many problems,” he says. In Bangladesh, the deck is stacked against addressing the issue.

The WHO estimates that arsenic exposure will kill nearly 43,000 Bangladeshi’s per year. That figures means that 1 out of every 18 Bangladeshi men, women, and children will be poisoned to death.

In Maine, politics thwarted attempts to fix the contamination. In the summer of 2015, Democratic State Representative Andrew Gattine presented a bill to tackle the problem. The bill would have required testing for arsenic in well water when selling a house. Other tests are already part of the home inspection process, and testing well water for arsenic would have been added to the list. The bill would have also funded a public awareness campaign about the arsenic problem. To pay for these changes, a small tax would have been applied.

The bill passed both of Maine’s houses of congress in June of 2015. It had strong bipartisan support, receiving 108 votes in favor and only 40 against in the Maine House of Representatives. Two weeks later, Republican governor Paul LePage vetoed the bill, calling it “unnecessary.”

“I think it came down to it looking like it was a tax,” explains Maine State Senator Amy Volk. “There are just some people who are never going to support increasing the cost on anything, or increasing the tax on anything.” Senator Volk was one of several Republican lawmakers in Maine who supported the bill, and even published an op-ed in a local paper in support of it.

There was also pushback from local real estate agents. “The realty agent industry just didn’t want to have one more thing to have to do to sell a house,” said Dr. Wasserman.

For a full mindmap behind this article with articles, videos, and documents see #water

For years, the US federal government had provided a grant of $300,000 to Maine to cover the cost of testing Maine’s water for chemicals. It was Maine’s only source of funding for the tests. When it came time to renew for the grant, the LePage administration chose not to submit the application. An official from Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services told local newspapers, “taxpayers should not be forced to subsidize, through grants, other people’s well water testing kits.”

While the neurological development of children is invaluable, the political inaction in Maine might be understandable within Maine’s context. The scale of the problem in Maine is not at crisis levels, making the cost-benefit calculation in Maine different than it is in Bangladesh. For that matter, as Dr. Wasserman put it, “It is just one study. Let’s be clear. It needs replication. I would not necessarily advocate enormous expenditure of public funds based on one study.”

In Bangladesh, however, the problem simply cannot be ignored. The Columbia team’s study in Maine found that arsenic concentrations as low as 5µg/L affected IQ. The Bangladeshi government’s safety standard is ten times that level, at 50µg/L. Levels below 50µg/L have been linked to increased mortality, and even if the 50µg/L level were safe, UNICEF estimates that around 22 million Bangladeshis still drink water with arsenic levels even higher than that.

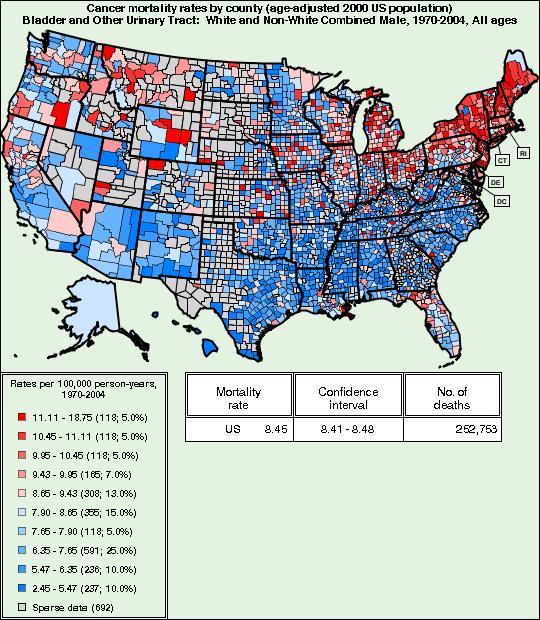

In the Photo: In areas with arsenic-contaminated well water, bladder cancer rates are much higher. Image generated via the National Cancer Institute web application.

The aftershocks of arsenic exposure will remain significant for years to come.

An estimated 13 million Americans are exposed to arsenic levels above the 10µg/L safety standard recommended by the EPA and the WHO. “If you look at a map of the United States for bladder cancer, New England lights up as the region with the highest risk,” Dr. Graziano observes. Other research shows an association between even low levels of arsenic exposure and deaths from other cancers, and newer research links it to heart disease deaths as well.

In Bangladesh, the effects of arsenic are even more striking. The WHO estimates that arsenic exposure will kill nearly 43,000 Bangladeshi’s per year. That figures means that 1 out of every 18 Bangladeshi men, women, and children will be poisoned to death. An entire generation of Bangladeshi’s has been exposed to arsenic. Heart disease, lung disease, and cancers will claim them, and their children will become what the WHO now calls “arsenic orphans.”

Rural Bangladesh and rural Maine are a world apart, but share the same problem. Their obstacles to fixing that problem are different, but the results are the same.

In each case, innocent people are drinking from poisoned wells that are quietly killing thousands.

Recommended reading: “BLUE GOLD: THE COMING WATER WARS”

_ _