Ever wondered about the myth of start-ups launched in a garage?

The story of Google’s founding proves that it’s not entirely a myth: the story starts in 1994 with the launch of the Digital Library Initiative (DLI) by three US government agencies, the National Science Foundation, NASA and DARPA. The aim was to promote innovation in “digital library research”, i.e. find ways to improve access and use of the information that by then was already piling up on the Web.

Among the first six winners of the new DLI awards, was a clever Web page indexing project, the brainchild of two gifted Stanford University students, Larry Paige and Sergey Brin.

The two built a prototype called BackRub based on Paige’s foundational insight that what matters in page ranking are the links between those pages because they are made by humans and therefore reflect at least some form or judgment or assessment about their use. With BackRub they tested their PageRank system, initially on 24 million pages. It was so successful that they got $1 million additional funding and by 1998, Page and Brin had moved their growing hardware facility from the Stanford campus into a friend’s garage in Menlo Park and started Google, Inc.

Over a year ago, Google took a leaf from its founding history and launched the Digital News Initiative (DNI) in Europe.

The similarities with DLI cannot be missed, they’re both “digital initiatives” with the avowed aim to support innovation with funding; and in DNI’s case, as Google puts it, to promote “high quality journalism through technology and innovation”. Awards are called “projects” and among the three types of projects financed by the DNI Fund, you have “prototype projects” going to individuals – while the other two types of “projects” are reserved to news publishers (see box for details of how the DNI funding works).

How the DNI Fund worksFrom Ludovic Blecher’s presentation, head of DNI Fund |

|

Summer round: Open – Closing date: 11 July 2016 |

| Three categories (“tracks”) of funding: |

| 1. Prototype projects: open to organizations – and to individuals – that meet the eligibility criteria, and require up to €50k of funding. These projects should be “very early stage, with ideas yet to be designed and assumptions yet to be tested”. DNI “fast-tracks such projects” and will fund 100% of total cost. |

| 2. Medium projects: open to organizations that meet the eligibility criteria and require up to €300k of funding. Funding requests up to 70% of total cost of the project are accepted. |

| 3.Large projects: open to organizations that meet the eligibility criteria and require more than €300k of funding. Funding requests up to 70% of total cost of the project are accepted and capped at €1 million. Possible exceptions to the €1 million cap for “large collaborative projects” (e.g., international, sector-wide, involving multiple organizations) or that “significantly benefit” the broad news ecosystem. |

| Eligibility: Open to established publishers, online-only players, news start-ups, collaborative partnerships and individuals based in the EU and EFTA countries. |

| Governance: Initial selection of projects done by a Project team, composed of a mix of “experienced industry figures and Google staff”, who “review all applications for eligibility, innovation and impact”. They make recommendations on funding for “Prototype and Medium projects” to the Fund’s Council, which has oversight of the Fund’s selection process. The Council votes on “Large projects”. More information and Council members listed here. |

| How to apply Visit the Digital News Initiative website for full details. Applications in English only. |

Oddly enough, DNI does not function in America for the time being.

That suggests one of two things, either Google is testing the ground first in Europe to see how it flies, or its hidden agenda with DNI is a charm offensive to woo the European news industry.

Is the charm offensive working?

Consider that just eleven European news organizations supported Google at the DNI launch in April 2015; today, 160 news publishers have joined as partners in the Initiative. They included some big names from the start, ranging from the Financial Times and Guardian (UK) to La Stampa (Italy), Les Echos (France), El Paìs (Spain), Frankfurter Allgemeine and Die Zeit (Germany). Moreover, we learn on DNI’s website, that now over 1000 organizations “across Europe have expressed interest”.

That’s remarkable. You could say that in a single year, Google has gone a long way to achieve its objective if it was to enter newsrooms around the continent and spruce up its image in Europe.

Admittedly, its reputation needed some dusting up, given the level of distrust and suspicion that American corporate digital giants, Facebook and Amazon included, tend to provoke on the old continent.

But it’s more complicated than that, advertising money enters the picture too. As ably argued by Newsomonics’ Ken Doctor, Google that used to be top dog in driving news traffic – especially in Europe where it is still the top search engine – is losing its bark to Facebook and LinkedIn that have both entered the news arena. Something needed to be done to reverse the digital onslaught on European news publishers and help them improve monetization of advertising.

So “entering newsrooms” required bringing something useful into the European news ecosystem. And Google did just that: it drew attention to its own products and digital know-how, and presented itself not as an enemy but as a “better partner” for journalists and media entrepreneurs as well as a promoter of innovation through a funding mechanism.

Exactly what Google means by “innovation” is kept deliberately moot on the DNI website, but in one recent video, it is described as “a process” by Ludovic Brecher, the man in charge of one part of DNI, the DNI fund for innovation. He insists that an innovative “project” need not be a wholly or partly digital app, it could even be a business model and it does not have to include Google products. This certainly counts as opening the doors wide to innovation in the broadest sense.

The video mentioned above was recorded at a recent workshop in Perugia (Italy) in April 2016, held on the occasion of the International Journalism Festival. The DNI team headed by Madhav Chinappa, in charge of Strategic Relations at Google, presented the three “pillars” that compose DNI:

- product development by a ‘product working group’ exploring product development to increase revenue, traffic and audience engagement;

- training and research resources to journalists and newsrooms across Europe with support from the Google News Lab;

- supporting innovation in digital news journalism through the DNI Innovation Fund, endowed with €150m (about $170 million) over the next three years.

While the video of this presentation is fairly long (over an hour), it clarifies what the first and second “pillars” of DNI are about: in fact, they include several attractive Google tools for journalists and news publishers, all of them freely available:

- AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages project) that speeds up a website’s upload time on smartphones and other mobile devices to ensure it doesn’t lose traffic; according to the video introducing AMP, Google data shows that if a website takes longer than 3 seconds to upload – something that can easily happen on smartphones – some 40 percent of customers are turned away; as Richard Gingras, head of Google News puts it, with AMP that is an open source project and loads news content “4 times faster than traditional HTLM”, Google wants to “make the web great again”; incidentally, AMP is not restricted to Europe, it is available world-wide;

THE VIDEO INTRODUCING AMP :

- Project Shield to prevent hacker attacks, especially the more common (and damaging) ones like DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service), a type of attack that unleashes a storm of requests big enough to bring down a website;

Project Shield Landing Page (screenshot)

- Google News Lab training sessions for journalists in the use of digital tools: there are four classes of tools, each presented through a short 5 to 20 minutes “lesson”.

News Lab “lessons” (partial view – screenshot)

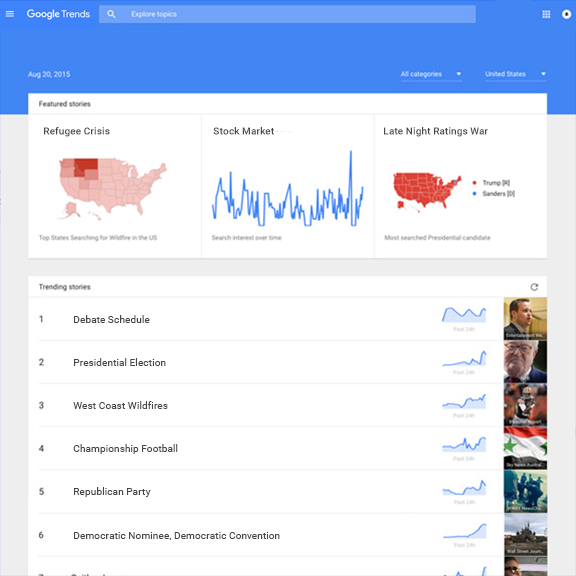

Among the more intriguing tools there is one to identify “trends” in Google searches that can reveal what kind of news might rank higher among readers and thus help increase traffic:

So far, 10,000 journalists in Europe have been reportedly reached by Google in this way in the past year alone, quite a feat.

Yet, at the Perugia workshop, in spite of the apparent success of the training sessions, it was only the Fund, the DNI’s third “pillar”, that got a hearty round of applause.

Since its launch on 22 October 2015, the Fund has been consistently presented by Google as a “bold initiative” intended “to spark new thinking” with funding made available “in the form of no-strings-attached awards over the next three years”. Google has made it clear that it does not plan to acquire any stake in the projects it funds and this is commendable. Also, there is no doubt that, in a digital-battered news ecosystem such as the European one, enthusiasm for the Fund t an injection of fresh funds is welcome. While the total amount set aside for the DNI Fund, €150 million, may seem like peanuts for a giant like Google flushed with cash, if handled well, it could undeniably have a positive multiplier effect.

At least two application rounds per year have been announced. The first, a winter round, closed on 4 December 2015, the second one, the summer round, will close on 11 July 2016.

Results of the First Round

By February 2016, Google announced it had awarded a total of €27 million in the first round to 128 projects selected out of 1236 applications. That’s 23 winning countries out of a total of 30 countries that had participated.

While it is too early to assess the impact of DNI on the European news ecosystem, now that the first round is over, it is possible to better grasp how the Fund really works.

The timing of disbursements could be slower than foreseen. At the time of writing, almost seven months after the first round closed (4 December 2015), it seems that many winners are still in negotiation to finalize their projects before the financing agreement can be signed. Moreover, once signed, it is expected that 10 weeks will pass before winners receive their first tranche of payments, 30% of the total award. These are fairly normal administrative delays, but they could impact negatively individual applicants, though not large news publishers that are much stronger financially.

Also awards are capped according to the type of project and only “prototype” projects are funded 100%. The others – “medium” and “large projects” – get a maximum of 70% of the budget requested.

This is not an unusual model for financing: for example, it is a fairly standard approach in official development aid (ODA) where the governments of the beneficiary countries are expected to provide their own share of the investment, usually 30% – including some physical infrastructure such as office space or land (depending on the nature of the project). And the beneficiaries of large and medium DNI awards being established news publishers can – and should be – expected to be able to pay for 30% of project costs. Their involvement is proof of their willingness to be serious about the project they propose. And in fact, DNI funding is not available for such things as office space, furniture or travel expenses.

“Prototype projects” however are a category apart, and they provide 100% of the request. This is commendable and makes sense since they are the only category opened to individuals. Also the assurance Google gives that it will keep all application details confidential is critically important to establish trust in DNI funding, and it is most welcome.

However, the fact that prototype awards are capped at €50,000 could prove to be a limitation. An individual may need more, particularly if the project is a complex app or she has no office space to work in. The exclusion of office space, furniture and travel from the grant could prove a problem. An individual DNI award winner could well find herself working in a garage due to shortage of funds.

In short, conditions for individual applicants are not particularly favorable, considering (1) the delays they might be facing between application, approval and actual disbursement; (2) the modest amount awarded; (3) exclusion of office and related work expenses. This means that DNI funding is not likely to attract start-ups. Even though the money provided under “prototype projects” is 100% of the requested budget, it cannot be expected to finance any important, ground-breaking innovation.

In fact, the DNI Fund staff noted that “prototype projects”, contrary to their expectations, had attracted established news publishers rather than individuals as they had hoped. And what news publishers! Overall, the money went in all three categories of projects to the likes of Agence France Presse (France), El Pais (Spain), Magnum Photos (UK) etc., mostly historically established big names in the European news industry, including some cross-country collaborative projects like Athens Technology Centre (Greece) with Deutsche Welle (Germany). The full list can be accessed on the DNI website here.

What Could be Done to Improve Funding Effectiveness

If Google wants to effect change in the European news ecosystem it will need to closely review its project categories, particularly the “prototype tract” that would need serious adjustment to attract true innovators, people capable of emulating the Google founders themselves, Brin and Paige. DNI awards should echo DLI awards.

The easiest remedial measure to take would be to exclude news publishers from the “prototype” category, and reserve it to individual applicants. Another measure would be to increase the award to €100,000, a sum far more consonant with what it really takes to test a new idea. Also, since these are individuals, the exclusion on office and related expenses should be reviewed.

Perhaps a look at how the National Science Foundation finances small business innovation research could inspire Google to make a revision to its DNI funding model. What NSF provides are grants in phases: a first phase of 6 to 12 months of $225k for a proof-of-concept/feasibility project; potentially followed by $750k for a longer development 2-year project.

Or take another example closer to the business of digital publishing: in 2007, a “standard grant” from NSF of some $75,000 was awarded to Julie Dorsey (Yale University) for one year to develop a novel approach to creating and editing 3D graphics. In 2016, her initial effort has bloomed into a full-scale project creating a small business called Mental Canvas, also financed by NSF – with the aim to provide a technology to “reimagine drawing in the digital age”, in short, a tool to sketch in 3D, very useful for scientists, architects and designers. NSF accompanied this innovator for nearly ten years…To support innovation, you need to be in it for the long haul.

From the garage where an idea is nurtured to the market where it is used commercially can take a long time, even in the digital age. And €50k won’t cut it. Unquestionably more is required to finance innovation if new ideas are ever going to see the light of day. And a longer commitment too, three years are not enough.

No doubt, Google could effectively woo European journalism, but it has to do it on two levels: attract the big players as it does now but also ensure that the small, independent players have a chance to make it. And European journalism would end up thanking Google for its revival.

If DNI funding works in Europe, what should Google do next? Bring it to America, of course.