Negotiations for a Global Plastics Treaty, which were held last week in Busan, South Korea, organized by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), and had some 170 countries and 440 organizations attend, concluded on December 1 without an agreement. Discussions and disagreements centered primarily on the vast amounts of macro plastics produced, the waste that must be disposed of, where it goes, who pays, and so forth.

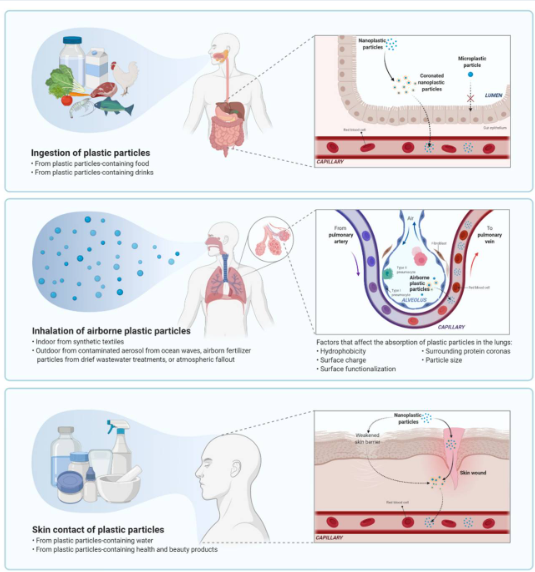

While most of the negotiations were conducted behind closed doors, from what is known, there was less focus on micro- and nano-plastics (MNPs) and the impact on health and disease from these minute plastic particles. MNPs are found everywhere: in the air, water, and land they are absorbed by plants, found in our foods, and in the bodies of humans and animals.

U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH)

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary U.S. national entity responsible for health-related research. It has a budget of $48 billion annually (in1980 its budget was nearly $3.5 billion; today its budget is almost US$ 50 billion, larger than the GNP of nearly 100 countries).

While there are occasional and annual reviews of performance and outputs and similar indicators (e.g., the NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools, which provide metrics on grant funding, the number of publications, and other productivity measures associated with NIH-supported research), there seems to have been no larger macro review of the institution and its budget as a whole in terms of national science priorities, federal fiscal policies or investment ratios (using, for example, the approach of comparative advantage, which includes as one of its prominent tenets the measurement of opportunity costs).

The NIH encompasses 27 separate institutes, complemented by many other federal entities, some under the Department of Health and Human Services, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the USDA, EPA, NSF, and NASA. As stated in an article included in the NIH National Library of Medicine, there is a need to better “understand how nano plastics are created, how they behave/break down within the environment, levels of toxicity and pollution of these nano plastics, and the possible health impacts on humans, as well as suggestions for additional research. This paper aims to inspire future studies into core elements of micro- and nano-plastics, the biological reactions caused by their specific and unusual qualities.” There is also a need to determine MNPs’ impact on reproductive health.

An Opportunity for the likely NIH Director, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya

President-elect Trump has named Dr. Jay Bhattacharya as his nominee for the next NIH Director. Much of the initial reaction has centered on his active disagreement with the past NIH COVID-19 response and its leadership. In 2020, Bhattacharya co-authored the controversial “Great Barrington Declaration,” which was co-signed by dozens of medical and public health scientists and medical practitioner co-signers.

In it, Bhattacharya and others argued for less reliance on COVID-19 vaccines and a general lockdown approach to avoid its spread while conceding that a more targeted shutdown for the more vulnerable, such as the elderly, would be reasonable. The Declaration stated:

“The most compassionate approach that balances the risks and benefits of reaching herd immunity, is to allow those who are at minimal risk of death to live their lives normally to build up immunity to the virus through natural infection, while better protecting those who are at highest risk. We call this Focused Protection.”

While his views on this subject, and especially vaccines, will be front and center during his confirmation hearings, Dr. Bhattacharya stands for much more than someone who has criticized the U.S. COVID-19 response. His background and positions are impressive: He has both a medical degree and a PhD in Economics, is a professor of Medicine at Standford University, a research associate at the National Bureau of Economics Research, and directs the Stanford Center on the Demography of Health and Aging. His research focus has been on the economics of health care, and in particular, the well-being of vulnerable populations, as well as on innovation and the environment.

Bhattacharya has made it plain he will seek to chart new paths for the NIH, its 27 Institutes, and how its future annual budget will be used. He would become the first Director of NIH with an intensive economic background, and this will be potentially important in terms of his intention to “reform American scientific institutions so that they are worthy of trust again and will deploy the fruits of excellent science to make America healthy again.”

Related Articles: INC-5: Ambitious Countries Are Failing the Planet | Major Gaps Remain in New Global Plastics Treaty Text Proposed by INC-5 Chair | What You Need to Know About the UN’s Draft Global Plastics Treaty | WWF Calls for a Global Ban on ‘Harmful and Unnecessary’ Single-Use Plastic Items Ahead of Key UN Plastic Pollution Treaty Talks | Draft Global Plastics Treaty Shows Promise | New UN Treaty Focused on Plastic Pollution | UN Treaty On Plastic Pollution: A Global Action Plan | Cities Are Key to the Success of the Global Plastics Treaty | How Micro- and Nano-Plastics Are Destroying Soil and Human Health

A Way Forward

First, consider how the NIH might approach its future, drawing on methodology that many large international organizations use to assess their effectiveness and relevance by taking into account the following:

- productivity growth of the various NIH institutes;

- efficiency of the various research programs;

- the cost-effectiveness of each additional budget allocation;

- which NIH institutes and programs have or could be closed or merged into other programs or institutes because of “no results” after many years or due to non-performance – or because the problem has wholly or partly been resolved (institutional inertia);

- the opportunity costs of each budget allocation for research: would the money have been spent better on other health and medical research programs, on other (non-research) health and medical programs (for the poor or the elderly, for example), on other research programs elsewhere (e.g., the material sciences to substitute for plastics), on other priorities of national importance (for example on bridge maintenance and repairs, water systems maintenance and repairs, other infrastructure, and so forth), or on programs such as better education for disadvantaged populations).

And specifically, here is a way to pursue his objectives: A much more extensive and intensive research agenda into plastics’ effects on health, including micro- and nano-plastics as causes of or contributing factors to diseases whose origins remain unknown and that are multiplying in sync with the increase of MNPs over the last fifty years, would be an important and valued subject and science priority.

Despite the failure of the Global Plastics Treaty to reach an agreement, there is growing worldwide public health interest in garnering more data on the widely prevalent and potentially harmful effects of such plastics on many childhood and adult diseases, as well as impacts on reproductive health.

U.S. leadership — hopefully in conjunction with leading European research institutes and programs — would be both important and welcomed at home and abroad. This could be a signature program for Dr. Bhattacharya to design, advocate, and fund, in keeping with his vision of the need for NIH excellence and the potential repositioning of its main priorities.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: Micro- and nano-plastics collected in Capraia Island. Cover Photo Credit: © Lorenzo Moscia / Greenpeace.