Given their omnipresence in our urban built environment, it is difficult to remember that cars have been around for only about a century. Walking and cycling, and later mass transit such as streetcars and trains, were the main means of transport that shaped urban environments until the early 20th century.

After 100 years of designing our cities around and for cars, the car-based mobility regime has shown its profound environmental and social flaws. Motorized road transport accounts for significant and rising greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. Moreover, traffic crashes are among the top three causes of preventable deaths and the first among children and young teenagers worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Finally, with cities around the world craving scarce, centrally located land, too much space is taken up by cars. Estimates in the European Union show that on-street parking occupies 8-12 square meters of public space, where cars stay parked over 90% of the day.

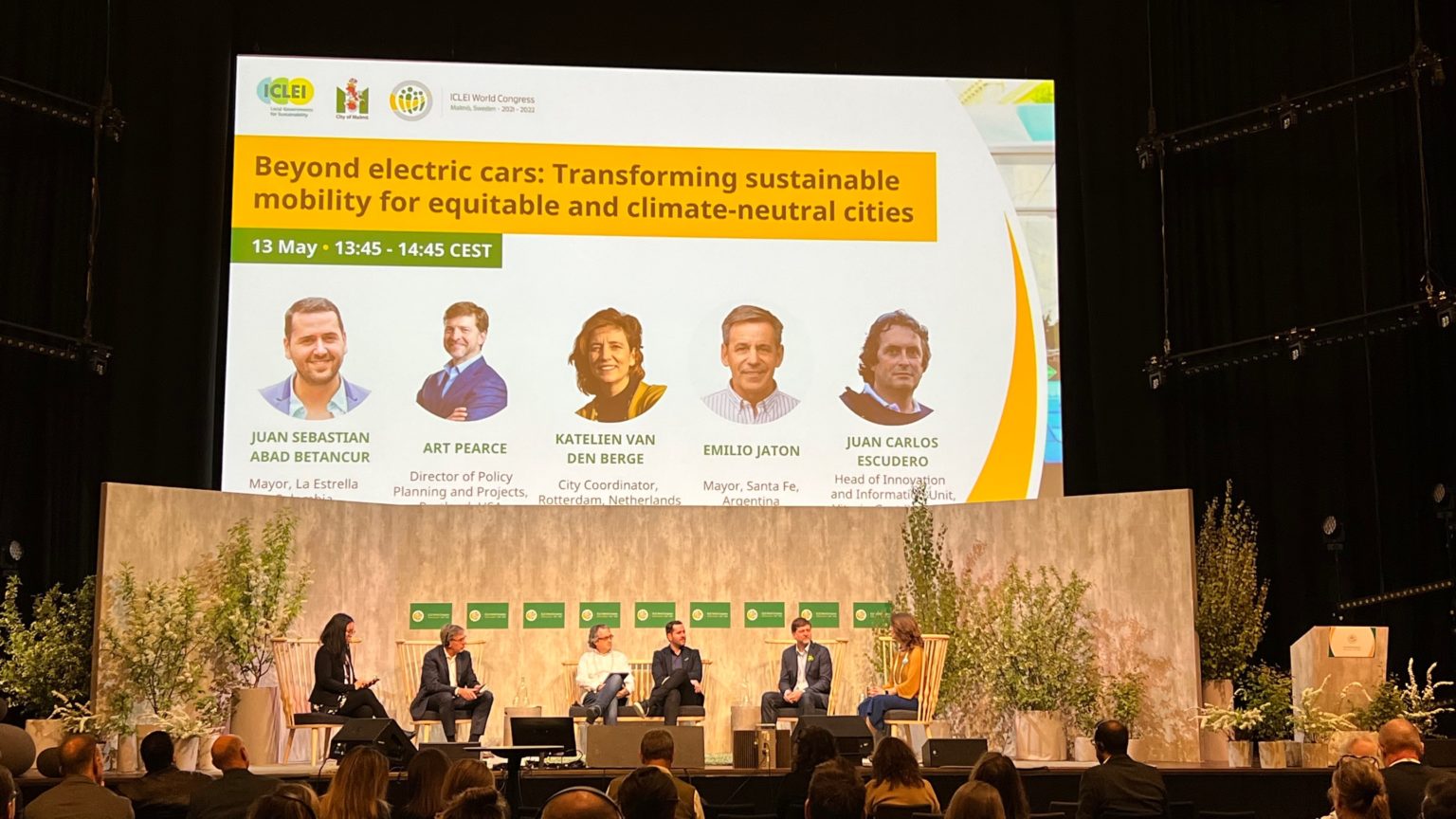

As part of the ICLEI World Congress in Malmö, Sweden, the Sustainable Mobility team brought together five-city representatives from European, Latin American, and North American cities to reflect on how to advance the transition to climate-neutral and people-centered mobility systems and cities.

The message was loud and clear: In order for cities to move forward, they have to go backward. In other words, to put active mobility and public transport at the center of city structure and urban life, cities must reclaim the space now occupied by motorized vehicles.

Here are five initiatives cities are taking to move toward more sustainable and equitable mobility for all.

La Estrella, Colombia: Tactical urbanism to put pedestrians first

From southern Latin America to Northwestern Europe, cities have successfully transformed their streets with tactical urbanism. By using inexpensive materials (painting, traffic cones, concrete jersey barriers, and planters), cities can quickly pilot, assess, and fine-tune new infrastructure such as bus and cycle lanes, pedestrian paths, parklets, and traffic-calming elements that could later become permanent.

Juan Sebastián Abad, Mayor of La Estrella, provided an outstanding example of such an initiative. Abad described the transformation of one of the city’s most important commercial and residential streets where traffic casualties, mostly involving pedestrians, were on the rise.

The four-lane street was reduced to two lanes to prioritize and safeguard pedestrians, making it possible to expand the narrow sidewalks and limit parking. By adding curb extensions and marking crosswalks, pedestrians were prioritized at three traffic intersections throughout the 200-meter project.

Two years later, preliminary assessments showed a substantial decrease in traffic casualties and revitalization of retail activities, Abad said. Currently, the local government is in the process of approving additional funding to make these road transformations permanent.

Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain: The BEI and revival of public transport

Vitoria-Gasteiz’s busiest bus routes, the 2A and 2B, operate around the ring road and provide mobility service to around 14 neighborhoods. Looking to improve the overall quality of service, the city government undertook a large-scale transformation of the seven-lane road to build the BEI (Bus Electrico Inteligente), the city’s first BRT system, which also is fully operated with electric buses.

The street redesign reclaimed space previously devoted to cars to allocate two dedicated bus lanes, bus stations, and created opportunity for charging infrastructure.

The project has shown remarkable results in just a few months. According to Juan Carlos Escudero, the city’s Head of Innovation and Information, the BEI has led to a 40% reduction in bus travel times in this corridor and is the only bus line that has fully recovered pre-pandemic ridership levels.

The BEI shows that when quality of service improves, making the bus not only more efficient but also more comfortable, mass transit becomes an increasingly attractive mobility option.

Portland, United States: Swapping parking spots for transportation passes

In 2017, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) began experimenting with affordable transit through its Transportation Wallet program, a digital ticketing system granting eligible city residents free access to mass public transit, as well as bike, scooter, and car-sharing systems. Since then, the program has been further developed and expanded.

Today the Golden Transportation Wallet strategically targets two types of users: low-income residents, many of whom live in the city’s outskirts, and car owners and commuters who voluntarily give up their on-street parking permits in the most congested areas of the city (Bike Portland, 2021).

A recent study of the Transportation Wallet program showed satisfactory results. Users reported that they were encouraged to try transit services they had not used before, reducing car use for around 60 percent of their previous motorized trips. The most significant achievement, however, was in equity. Eligible low-income residents said the program provided an enormous economic relief, making it possible to access city areas and services that they could not have gotten to otherwise.

Emphasizing how the city is transitioning away from individual, motorized mobility, Art Pearce, Director of Policy, Planning, and Projects at PBOT, explained that the Transportation Wallet is coupled with many other road space reallocation projects. These initiatives include expanding and improving dedicated bus lanes, segregated on-street bicycle paths, and broader, safer, barrier-free sidewalks. Altogether, Pearce said, the city aims at sending a clear signal: Cars are not only an unsustainable but an inconvenient and expensive way to carry out short trips within the city core area, which has plenty of other more affordable and efficient alternatives.

Santa Fe, Argentina: 30 km/h zones promote safe, efficient non-motorized city transport

From Buenos Aires to Brussels, the adoption of 30 km/h zones worldwide has proven to be an effective way to significantly reduce traffic accidents while making urban environments more walkable and cycle-friendly.

Driven by the same ambition, Santa Fe’s current administration, led by Mayor Emilio Jatón, proposed the implementation of Ciudad 30, a 30 km/h zone encompassing the city’s historic center. The initiative, approved by the City Council in August 2020, will include the construction of bicycle parking infrastructure in all public buildings and the extension of bike lanes in the central neighborhood of Urquiza.

Rotterdam, Netherlands: Charging forward in the Dutch cycling revolution

After being completely destroyed during World War II, post-war Rotterdam was rebuilt following modernist urban planning principles, including as a car-centric city. By Dutch standards, it has historically had one of the lowest rates of cycling among the four big cities in the country, around 18 percent compared to 30 percent in Amsterdam and 31 percent in Utrecht (Onderzoek en Business Intelligence, 2013).

In the early 2000s, a coalition of local government and civil society organizations began to defy this trend by undertaking a massive transformation of Rotterdam’s road network in favor of cycling. The results are indisputable. In the last decade, cycling has increased by around 40 percent, representing almost a third of the daily trips made within the city boundary (ECF, 2022).

Related Articles: 19 Startups That Will Shape Our Cities Selected By Mobility Lab 2022 | Colombia’s Capital Leads in Sustainable Transportation and Clean Mobility

Katelien Van de Berge, City Coordinator of the RUGGEDISED project, said Rotterdam’s decisive commitment to boosting urban cycling can be seen in decisions at all levels. On the large-scale level, the city has revitalized its central street, the Coolsingel, added hundreds of new kilometers of cycle lanes, and created thousands of new bicycle parking spots in state-of-the-art parking facilities. On the small scale, the city is incorporating rain sensors across its traffic-light network to give the right of way to bicyclists when it is raining.

Stakeholder engagement is critical across the board

A common theme across all insights shared by city representatives was the importance of actively engaging all stakeholders across all stages of a project regardless of scale. From workshops on how to modify a car lane in La Estrella to consultation on refiguring the entire bus route system in Vitoria-Gasteiz, panelists addressed active participation as crucial to integrating multiple needs and interests and ensuring political and social buy-in.

Despite substantial progress, our panel of speakers called for only moderate optimism. Unanimously, city representatives acknowledged that the most significant transformation is yet to be seen, not in the built environment but in people’s mindset. Cars are still intensely perceived as symbols of status, success, and freedom, explaining why even in cities like Vitoria-Gasteiz and Rotterdam, where conditions would seem to favor more sustainable modes of transport, it remains challenging to pull people out of cars. Although the question of how to accelerate cultural change remains open, city representatives highlighted that spatial reconfigurations are without a doubt an effective way to propel such behavioral change.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Public rental bicycles in a city. Featured Photo Credit: Sittikan Raingkun.