Stay in or Leave the EU? The Consequences for Britain and the EU

The European Union is facing a perfect storm and possibly its greatest test since its six original members, France, Germany, Italy and the Benelux countries, began the European Project in 1957 with the signature of the Treaty of Rome.

What the EU did not need at this point was “Brexit”, the possibility of Britain voting to leave the EU on June 23, the date set by Prime Minister Cameron for the referendum on leaving the EU.

Consider the situation:

- a long-simmering Greek debt crisis that has battered the Euro since 2010 is coming up for yet another call for bailout funds in July with Germany unwilling to consider the only possible solution, i.e. debt relief (as proposed by the IMF);

- the double-dip recession – a fate the US escaped thanks to the quantitative easing measures taken by the Federal Reserve but that could not be replicated by the European Central Bank due to a relentless German opposition, led by the German Finance Minister Schauble who has a pre-Keynesian fear of inflation and a fixation on “balancing the budget” at all costs;

- continuing high levels of unemployment everywhere, especially among the young (up to 50 percent in Spain and Greece are jobless) and harrowing poverty in some places (in Greece, the national health system has broken down leaving the poor with no protection);

- unprecedented flows of refugees, well over one million entering the EU last year, as the war in Syria took a turn for the worse with the Russian bombings.

Even the relatively good news of renewed (if weak) EU growth this year has not succeeded in slowing down the rise of a vicious form of nationalistic populism across the continent. New parties on the extreme right have been loudly calling for a denial of asylum and closure of frontiers. Unfortunately, they have been heard by feckless politicians too fearful to stand up for their convictions (possibly with the exception of the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, though she too has lately weakened her stance). And we are seeing this even in countries that not so long ago were very liberal, like the Netherlands and France.

Remarkably, the only country that does not seem to have veered in this ugly direction is Italy – possibly because it was the first EU member to bear the brunt of refugee flows, as far back as 1998, and it has learned to cope with it, all by itself for a long time as other EU members looked on, unwilling to lend a hand.

But this is a small bright spot in the whole picture.

The overall result of all these unfortunate events is inescapable: what was originally a cautious distancing from Brussels and the European Project calling for an ever “closer union”, has now turned into an unbridgeable chasm, as the Schengen rules for visa-free travel are suspended again and again, even between close neighbors with historically friendly relations like Italy and France.

Why did Brexit Happen at All?

Simply put, it was Cameron’s fault – some called it a “gamble“. He thought he could woo the euro-skeptics in his party; the Conservatives are notoriously and historically anti-Europe and pro-Empire. So he promised them a referendum on the EU. He thought he’d also bring them a “sweet deal”, a renegotiation of the UK relationship with the EU, to try and swing the balance of the party to the “remain-in-the-EU” position.

In the photo: President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz’s meting with British Prime Minister David Cameron in Brussels on February 16, 2016. Photo credit: © European Union 2015 – European Parliament.

That is why last year he withheld (or down-played? We shall never know) the discussion of the UK Competences Review – a massive 3,000 page report published in March 2015 by the House of Lords that would have immediately made it clear that the benefits the UK derived from the EU far outweighed costs. But to draw attention to this message so early in the game was not in his plans. He wanted to be free to go to Brussels to negotiate a better “deal”. In the end, his EU partners were unwilling to give him much rope, they knew that the UK was already paying less than its due and had been benefiting from favorable conditions ever since it joined the EU in 1973.

So the deal Cameron came back with amounted to minor tweaks, not big enough to change the opinion of Brexit backers. And soon enough, Boris Johnson, whose position as Mayor of London was coming to an end, saw a political opportunity in embracing Brexit, vying for the post of Prime Minister in case the UK voted to get out (a situation that would cause Cameron to leave).

A Lose-Lose Situation

In game theory, Brexit would be described as the reverse of a win-win, it is a “lose-lose” situation.

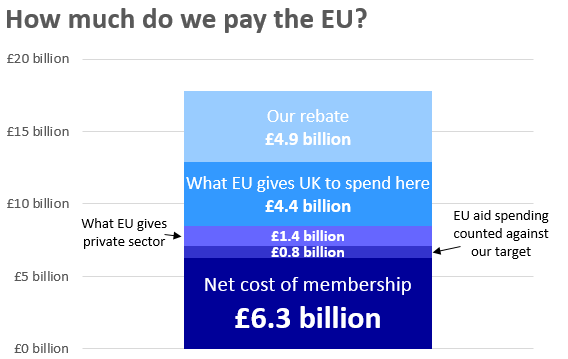

Euro-skeptics love to point out that EU membership costs the UK £55 million a day. That figure was pulled out by Full Fact, the fact-checking site in 2014 but in February 2016, they came out with a new piece of research, reversing their finding. Belonging to the EU in fact works out to a minimal cost for the UK: the net cost is £120 million a week or £17 million a day – about 26 p per person. As pointed out by Hugo Dixon in his InFacts article, that’s half the cost of a Mars bar.

Why so little? There are several reasons. First, the UK gets an automatic refund: while it sends £250 million a week to the EU, the notional contribution should have been £340 million a week, so it directly gets a rebate worth £90 million a week; second, the EU funds farming and regional aid to the tune of £4.4 billion in 2015; third, the EU finances private sector research in the UK, the last published figure were for 2013 and show that Brussels sent £1.3 billion for the purpose. In fact, the EU spends in many areas, including art and culture. The table below summarizes the situation:

Source: InFacts.org

The UK exit would trigger Article 50 of the Rome Treaty that calls for a withdrawal agreement to be negotiated within two years (the actual mechanics for applying this article are debatable: it’s never been applied). In this interim period, EU laws would still apply in the UK, but the UK would no longer be allowed to participate in policy discussions in Brussels.

In the likely event the negotiations fail, the UK would return to the default trade agreements with the EU “governed by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules” – technical speak to say that the UK would become just like any other state dealing with the EU with no trade preferences of any kind: EU external customs duties would apply to all UK goods and services, including non-tariff barriers such as permits, licenses and other regulations.

Whether, in the two years following Brexit, the UK would manage to obtain a trade agreement with the EU along the lines of Norway (which allows it full access to the EU against payment of dues as if it were a member – yet with no say in EU policy-making) or choose to be treated like any outsider under WTO rules (like, say, Canada), everyone is worse off and here’s how.

Without going into technical details, the economic impact of Brexit can be summarized as follows:

- The UK immediately loses economically and loses big: every serious economic think tank has reached that conclusion, from the Institute for Fiscal Studies recent analysis, the Pricewaterhouse Coopers report commissioned by CBI, and an Oxford Economics study to the reports from the UK Treasury, the OECD and IMF – see articles listed on Thingser under #Brexit; the pound could slump by as much as 20 percent, and according to an S&P warning, it could even lose its status as a reserve currency used in world trade (and could imperil the UK’s AAA rating); this would obviously drive up the cost of imports, businesses would fold as demand drops, jobs would be cut (as much as 950,00), foreign direct investment (FDI) would inevitably slow down – it is already down due to the uncertainty Brexit has caused, along with the value of the pound that by mid-May had lost 6%: for example, it is reported that some 100 German businesses are scaling back their investments in the UK, waiting to see what will happen; the drop in GNP, 3 percent by 2020, 6 percent by 2030 according to the UK Treasury, is the equivalent of a tax on every household – at least £2,600 under the most optimistic scenario and £ 5,200 in the more pessimistic case where Britain is driven to make trade deals under WTO rules; the Bank of England Governor, Mark Carney, warned that Brexit carried the risk of recession; in short, Britain’s GNP loss would be such that from its current ranking of 5th economy in the world, it could easily fall behind France and even Italy, finding itself at the level of Brazil; within Europe, it would immediately lose Gibraltar as Spain has announced it would reclaim it “on the next day”.

- even the City’s primacy is at risk: London, in spite of its historic importance, will take a beating, including in real estate values and tourism but the first notable loss will be in euro-trading, in particular the 3 trillion euro-derivative market that is run from London, much to the dismay of the European Central Bank; expect the Bank to move fast to put it under its jurisdiction, either in Frankfurt or elsewhere as long as it is in the Euro zone.

- The EU also loses economically – proportionately much less than the UK, but still a loss, a drop in GNP estimated at 0.05%, accompanied by a loss of jobs and a trade loss, especially among countries that do a fair amount of trade with the UK, like Belgium or Denmark.

Yet the overall loss to the EU would be clearly milder and could even lead to probable gains in foreign direct investment – up to now, 20% of FDI to the EU had been directed to the UK, but this outsized percentage would not be maintained after Brexit. What we might see next is the rise of Frankfurt as a major European financial hub, provided it can maintain the quality of financial services that the City of London is known for.

Also, the EU has a distinct advantage over the UK: it’s a huge single market, and if Germany would stop relying on exports as its principal engine of growth and start to boost its consumer spending, it could act as a locomotive for Europe, pulling the whole continent out of recession – whether the UK is part of it or not. This is not a pipe dream anymore: there are signs this quarter that this is in fact happening. Germany has more than doubled its rate of growth even though some of its big markets, like China, are stalling. There is no magic to this: a EU rebound caused by Germany would be the predictable result of a fully functioning free trade area that ensures the rapid transmission of economic trends from one end to the other of the Union, accelerated by its single currency, the Euro.

In short, the economic argument is closed. Brexit is going to be played entirely on political grounds.

How likely is Brexit?

Highly likely – though it is a difficult question to settle. According to the pundits, it is a very close call. However, at the time of writing, there were some signs that the Remain campaign may be gaining ground and the value of the pound had recovered somewhat as the corporate bond market showed renewed vigor – yet markets could get jittery the closer we get to the referendum.

In the photo: If UKIP were pigeons, Clacton-on-Sea Banksy – Photo credit: Banksy

New issues could arise, for example, the latest figures for migration: when they came out in late May, they showed “record highs“. The Leave campaign immediately latched onto them, depicting a rosy post-Brexit world where the British government would be able to cut migration down to what it had promised, from the current 300,000 figure to 100,000. The Remain campaign was quick to point to the advantages from migration: (1) in a post-Brexit situation, the UK would lose the advantage of participating in the EU free movement of labor that underpins productivity rises and provides the Treasury with more tax money paid in by migrants; (2) only the most restrictive future trade agreements would allow the government to close borders to migration, causing “alarmingly high costs” for no “compelling economic advantage.”

Actually, immigration is a non-issue: economic evidence is strong that immigration creates wealth. It certainly has done so for Switzerland where the non-national population is 23.8 % and Norway where it is 9.4% – both much higher than the UK’s percentage of non-nationals at 7.8%. And both countries have a much higher per capita GDP, around twice as much – and they have a lower unemployment rate than the UK.

Still, at the time of writing, it’s too early to predict how it will go and there is a large portion of the population that is undecided.

The world of celebrities, artists, actors, musicians and writers has recently come out in favor of the remain camp in an open letter published in the conservative Daily Telegraph on 19 May. The letter is signed by 250 “luvvies”, as the British like to call them. Big names are included, like Benedict Cumberbatch, Jude Law, Helena Bonham Carter, Keira Knightly and Paloma Faith, and among writers, John Le Carré, Hilary Mantel and Philip Pullman. Architect Richard Rogers, fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, Oscar-winning director Danny Boyle and British poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy are also among the signatories. The letter stated unequivocally “Britain is not just stronger in Europe, it is more imaginative and more creative, and our global creative success would be severely weakened by walking away.” Not to mention the funding support to the arts coming out of Brussels: according to Creative Europe Desk UK, the EU provided grants to the UK worth €40 million over the past two years (about $45 million).

That is certainly a blow to Brexit proponents though some heavyweights like actor Michael Caine, Who frontman Roger Daltry and former England cricketer Ian Botham are all backing Brexit.

It is well known that older Britons – over 60 – are in their majority opposed to EU membership and that support for remaining in the EU is subject to regional variation and is higher in Scotland and in London.

Some say that the millennials could make a difference, the world of free travel to the EU for work or study is the only world they know. Will they give it up for the unknown of closed borders? The Financial Times has pointed out the millennials would bear the brunt of the cost of Brexit – in a Brexit-induced recession, they would be the first to suffer from a drop in jobs, as is usually the case with the young, and for that matter the poor and more vulnerable groups, as Cameron recently underlined. And yet, in spite of this, millennials were less likely to vote, leaving the field open to Brexit.

Another aspect in favor of Brexit backers clearly comes out in local political debates, in particular the ignorance displayed by voters and the abundance of deceptive talk from politicians that can easily embroil an unprepared public – as exemplified by recent statements made by Nigel Farage, the head of UKIP, one of the leaders in the pro-Brexit fight (see box below).

The tone is isolationist, the focus is on “Britain first”, a proud call for return to glorious Victorian days – something eerily echoing Trump’s slogan of “America first”. Boris Johnson recently came out with a view of the EU as yet another misguided attempt to unite Europe along the lines of Napoleon and Hitler, a comparison with Hitler that instantly ignited the ire of the EU President Donald Tusk.

It is as if the whole world were suffering from a backlash against globalization and a deep distrust in the benefits of free trade, no longer viewed as a panacea but as something that threatens jobs at home and hurts the working classes.

Fishermen along the British coasts are said to welcome Brexit; in their view, the opening of “their” waters to large fishing ships from EU countries such as Spain and France has put a dent in their income, they want to regain “control” of their waters (out to the 200 miles that belong to Britain, as per international rules). But this overlooks the benefits from EU fishing policies, the fact that they helped rebuild fish populations since 2003. British waters were overfished long before the EU fisheries policy were in place in 1983 and with the EU requirement that fishermen reduce fleet sizes and could fish only a limited number of days each year, the North Sea cod, according to recent data, is now recovering and is likely to be certified as sustainable by 2017.

Likewise, workers in British factories accept migrants with difficulty and the Labour party is having a hard time garnering votes. A BBC journalist who recently took a trip to Preston in north-west England to visit Beech’s chocolate factory established there since 1920 reported that “many of the workers hark back to a time when they believe Britain was a better place. Fairly or unfairly, they blame the EU for the change.” One of the women sitting beside the conveyor belt packing chocolates said that the National Health services were “stretched to the maximum… more people are coming in and it will be stretched even further, and I think the borders need to be controlled a bit more.”

Nobody wants to appear racist, but they are uncomfortable with foreigners. Arguments put forward by the pro-Remain camp are ignored: the fact that 350,000 jobs in the region are linked to trade with the EU; that 25,000 jobs have been created or protected by EU investment projects in the last five years, and that the region received £996m in European structural funds between 2007 and 2013. Many of the women told the reporter that they had stopped voting because they distrusted the politicians, in short, they no longer followed Labour’s guidance.

This situation of distrust and brushing off of the facts can only play in favor of a Brexit vote.

In the photo:British MEP Nigel Farage, Co-president of the Independence/Democracy Group and one of the EU’s most outspoken critics. Photo credit: © Bernard Rouffignac

BREXIT CAMPAIGN ARGUMENTS DECRYPTED – as stated by Nigel Farage (UKIP)

| PRO BREXIT | REBUTTAL |

| Open-door migration has led to an over-supply in the unskilled labor market, pushing down wages and the standard of living for many | Not true, overtime wages go up. Evidence is “mixed”, see here Immigrants and natives are “imperfect substitutes in the same skill group” |

| You cannot control your borders inside the EU. We have no control over the quality nor quantity of those coming into Britain, putting our infrastructure under huge pressure.

No government can plan sensibly for the future, for example, on school places if we don’t know how many people will be coming here each year. |

Not true. The UK controls borders very strictly, e.g. migrants cooped up in France’s infamous “The Jungle” near Calais cannot enter the UK – with Brexit, France will stop cooperating.

Numbers are highly predictable and reported every year, no reason why the government cannot plan – and it does. |

| The current level of migration is running at a record high, a third of a million a year.

With countries like Turkey looking to join the EU shortly, supported by David Cameron and Angela Merkel, the numbers are likely to increase further still. |

Unjustified hysteria. European Union nationals paid more than £3bn in income taxes while claiming about £0.5bn in HMRC benefits in 2013-14; UK gains £20 bn from European migrants, UCL economists reveal

Turkey is not about to join the EU anytime soon. Even if Turkish citizens win right to enter the EU visa-free, UK is not concerned since it has always been outside the Schengen area. |

| The EU is an outdated concept ill-equipped to deal with the challenges of the modern world such as global terrorism. The EU’s commitment to open borders makes us far less safe. | Not true. UK is safer staying in Europe: this is the informed opinion of two former chiefs of UK security services (here) Cooperation with 27 EU members is key to tackle terrorist threats. |

| I believe in Britain. We are good enough to run our own country, make our own laws, negotiate our own trade deals and control our own borders.

The sensible, patriotic choice is for Britain to Leave the EU so we are once again an independent country free to act in our own national interest. |

The British, like every other EU member, has the right to run their own country and control their own borders.

Patriotic but costly choice, at least £2,600/household, and up to £5,200 in the case of trade deals under WTO rules. Loss in GNP: at least 3% by 2020 (OECD) and 6% by 2030 (UK Treasury) The UK will fall behind France and even Italy. The UK will lose forever the benefit of belonging to a single market of 500 million people and of having a say in setting policies in Brussels. Expect a “protracted period of uncertainty” (IMF). Expect the possibility of a UK break-up with Scotland choosing independence and joining the EU. |

The Political Consequences of Brexit

With Brexit, the Cassandras are quick to point out that no matter what happens to the UK, the EU will also hurt: not only will it lose a major member, but Brexit opens the door to more “exits” from disgruntled EU members, as the Italian Minister of Finance Pier Carlo Padoan recently warned in an interview with Britain’s Channel 4 television, saying it could “act as a detonator” leading to “fragmentation” of the union.

Fragmentation is indeed a very real risk, as demands for “exit” will no doubt come from Eastern European member countries – notably Austria, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia, all in the hands of populist, nationalist governments. These countries, all recent EU members, are already dissatisfied with Brussels demanding they take on refugees and criticizing them for “democracy deficits” as they lurch towards increasingly autocratic governments.

Demands for exit could also come from the heart of Western Europe, in particular two key countries: the Netherlands where a recent no-vote on the EU policy towards Ukraine got the exultant support from Geert Wilders, the leader of the Freedom Party (it came out third in the 2014 parliamentary elections) and France whose historic tendency to “exceptionalism” and chauvinism has been recently exacerbated by Marine Le Pen’s political successes. Moreover, if Scotland, turned off by a successful Brexit vote, manages to secede from the UK, it will set an example for other independence-minded people, like the Basque, the Flemish, Tiroleans etc.

Assuming that a Scottish secession won’t happen and that the UK won’t break apart, it is still a fact that the UK, once delinked from the EU, will drop back to its “real” standing in the concert of nations, inevitably becoming a “second-rank” nation that will need to closely toe the American line if it wants to make its voice heard. Every future British PM will be the US President’s poodle (as Tony Blair was once famously said to be).

The International Monetary Fund sees the problem in more global terms: in a worst case scenario, the slowdown would not be limited to the UK or the EU but it would spread to the whole world, as the EU, a huge market of 500 million people – in fact, the largest GDP entity on a global level, ahead of the US, larger than China and Japan combined (IMF data) – is rocked by Brexit.

The question is: why do Europeans, already faced with so many problems (migrants, debt, unemployment, slow growth), should choose to add yet one more problem to all the others? Why this laceration and desire to self-destruct? Ignorance, a deficit in understanding the real challenges they are facing? Left-over nostalgia and a yearning for an easier age where one’s identity was not challenged by globalization?

Brexit really brings out the ugly side in European politics, a return to a chauvinistic past, a lack of compassion for the plight of others, an egotistical retreat behind walls…

In the photo: On Saturday 12 May, the European Parliament joined other EU institutions in Brussels in opening its doors to the public – Photo Credit: © European Union 2012 – European Parliament

Looking Forward: The Myth of “Ever Closer Union”?

As a thought experiment, suppose Brexit fails and the UK votes to remain in the Union, what happens to the EU as a whole?

Many economists have tried to imagine the answer, and one of the more interesting ones comes from Gregor Irwin who published his views on the London School of Economics platform.

He argues that the “UK deal” Cameron managed to obtain from Brussels at the start of this year will come into force, and while it will not cause the kind of devastating changes Brexit would, it would nonetheless push in the same direction: “ever closer union” for the other EU members (if they wish it) and none of it for the UK. And no doubt, some will want to follow the UK example: the deal Cameron got for the UK sets a precedent that cannot be brushed off.

Thus, the EU goal of “coming closer together” is further weakened whether we have Brexit or not, though a backlash could happen, as more and more European citizens wake up to what it means to live in a fragmented Europe, a step back into “second-rank and third-rank status” for each and every member that decides to “opt out”.

But there is yet another aspect to Brexit – should it happen – that cannot be overlooked: the UK would not be able to exercise its influence and put the brakes on Brussels the way it has done so far; it would be out of the EU negotiations game once and for all. This could accelerate decision-making, and it could even be salutary as there is a real possibility that the “historical core” (the six original member countries, Germany, France, Italy plus Benelux, known as the “Inner Six”) find a new voice and are revived.

At least one prominent British commentator, Anatole Kaletsky, is of the view that we could have a “Roman Europe”. He argues that Italy could make a difference, that there are several prominent pro-Europe Italians in power positions that are contrasting German policies: Draghi at the European Central Bank, Padoan, the Finance Minister who is a promoter of financial stimulus, the EU High representative for Foreign Affairs, Federica Mogherini, pushing for more pragmatic policies in Libya and for refugees. Also Prime Minister Renzi has been able to push through pension, labor and administrative reforms as Italy, unlike France, Germany, Spain and the UK, is relatively free from the obstruction of nationalistic, populist movements.

Can Italy lead a revived Europe? This remains to be seen and it is unquestionably a long shot.

One possibility might be that the EU will move towards a “variable geometry” model, with a fast-moving core while the periphery is splitting into nationalistic, second-rank members. It is likely that the “Inner Six” would take under their wing Southern Europe because of close trade and financial links (remember the bailouts of Greece, Portugal, Spain, Cyprus – in every case, Germany played a key role). Ireland however is likely to remain out of the game: it’s a special case with a tax regime that favors big business and this is not to the liking of anyone in the EU. But Southern Europe is a political must: it’s a geo-political bulwark for the EU in the Mediterranean – a back door as it were, and it needs to be secured.

So what is the future likely to look like after the dust has settled?

All member countries unwilling to “come closer” and tempted to follow the UK example will work out “deals” with the EU, perhaps going as far as following Norway’s example, substantially breaking off with Brussels in order to preserve their sovereignty while maintaining the trade channels open (and some) financial relations. The most likely countries to opt out in this way are Eastern European (Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Slovenia…) and North European (Denmark, Finland…)

The silver lining? A “core” EU that survives – the “Inner Six” plus Southern Europe, 11 countries in total – politically much stronger than the pre-Brexit EU ever was…

Winston Churchill’s vision for Europe might yet come true, when in a famous speech in Zurich in 1946, he called for “a kind of United States of Europe” (at the time, he viewed it as led by France and Germany). He didn’t think the UK should be part of it, but he saw it as an indispensable bulwark against the kind of devastation brought by the two World Wars.

Winston Churchill’s vision for Europe might yet come true, when in a famous speech in Zurich in 1946, he called for “a kind of United States of Europe” (at the time, he viewed it as led by France and Germany). He didn’t think the UK should be part of it, but he saw it as an indispensable bulwark against the kind of devastation brought by the two World Wars.

Acceptance of the EU increased in Britain only when Margaret Thatcher obtained her notorious “UK rebate” in 1984, reducing the costs of UK participation in the EU, effectively turning the UK into what Professor Stephen George called in his 1990 best-selling book an “awkward partner”; yet she was also one of the architects of the first major revision of the Rome Treaty, the Single European Act (1986) aimed at creating a single market by 1992. It was only later, once she was out of government, that she appeared to have been drawn to the idea of leaving Europe.

But while she was in power, she was always a pragmatist who believed in the advantage of being in rather than out; she knew the difference between head and heart. Will the British follow her example?

Cover Photo: President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz’s convoy arrives at Number 10 Downing Street, where he met with British Prime Minister David Cameron in London on June 18, 2015.

References –

Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), Brexit and the UK’s Public Finances (IFS Report 116) London, May, 2016

IMF, United Kingdom—2016 Article IV Consultation Concluding Statement of the Mission May 13, 2016

OECD, The Economic Consequences of Brexit, A Taxing Decision, by Rafal Kierzenkowski, Nigel Pain, Elena Rusticelli, Sanne Zwart, OECD France, 28 Apr 2016

UK Treasury, HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives UK, 18 April 2016

The Review of the Balance of Competence between the UK and the EU, Published by the Authority of the House of Lords, London, 25 March 2015

Leaving the EU: Implications for the UK Economy PWC/CBI report, UK, March 2016

Assessing the Economic Implications of Brexit (Executive Summary) Oxford Economics Ltd. March 2016