For much of recent times, many would characterize the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, two Islamic countries that share vast oil wealth and small populations, as having a relatively modest footprint on world matters. Regional issues were all they appeared to be focused on, such as the Sunni/Shiite differences or Israel/Palestine clash, and nervous awareness of a looming Iran. In both cases, massive oil natural resources, lifting their sovereign wealth to an unimaginable scale, enabled them to ignore problems rather than solve them. Or, as will be argued here, enabling them to resort to “greenwashing” and “sportswashing” as a way to cover them up.

Both have emerged now as visible and significant actors in subjects with wide implications for the global north and south. These newborn stars on the global stage, so to speak, come with customs, political structures, and pasts that warrant looking into, both in terms of strengths and weaknesses.

For this article, the lens is limited to how each country is treating a particular issue that it feels is drawing unwanted attention from the world. Thus the host of actions, policies, treatment of opposition or immigrants, and so forth that these countries may also be engaged in is not covered here.

Instead, the focus is on a particular political behavior they both engage in and that one could term “washing”. Whether applied to environmental or other issues, “washing” boils down to a series of sophisticated attempts to build up a good image and add to the country’s “soft power”. Arguably, “washing” is an expression of “soft power” enabled by extreme wealth. And it appears to be a widespread practice among those two countries, as each pursues its own kind of “washing” to cover up practices that damage its reputation.

Let’s take a look at each.

United Arab Emirates: “greenwashing” fossil fuels at COP28

UAE has put itself forward as a leader in addressing climate change, as it hosts COP 28 in Dubai. This is, of course, the latest international gathering in the now 28-year-old process the UN is engaged in. A process better known as the climate framework convention, the UNFCCC, whereby the UN tries to push the world into doing something constructive to address the growing threat of climate change.

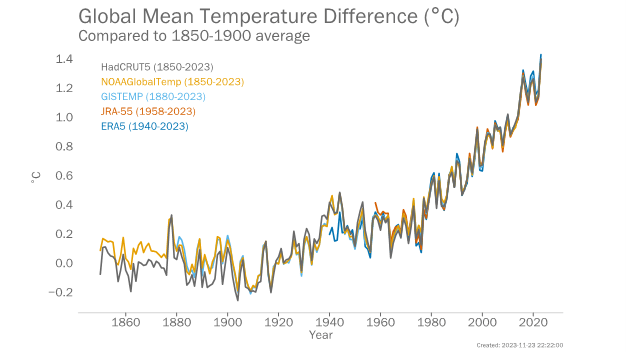

And as everyone knows, 2023 is set to become the hottest year ever on record, as confirmed by a just-released World Meteorological Organization report:

As the COP 28 host, the UAE has asked the world to focus on the promise of future technologies that would help contain CO2 emissions – for example, capturing carbon emissions and burying them deep underground, something that many countries in the north see as potentially feasible, including the European Union.

Yet, for all the promise, it is hard not to see such efforts as something very close to “greenwashing” of fossil fuels. Particularly when considering two additional aspects of the UAE official position:

(1) The COP 28 conference chair is the UAE Sultan al Jaber, CEO of the State-owned oil company, ADNOC: He presents himself as a green advocate calling on energy groups to get ready for a “phase down” of fossil fuels; also he likes to refer to his support for the creation of Masdar, meant to be a “green” city – yet such “green credentials” beggar belief when he is currently running the national oil company not as a distant figurehead but as an active and effective CEO;

(2) the UAE has reportedly tried to turn the upcoming COP 28 venue into an opportunity to make oil deals.

This is at a time when a key item on the COP 28 agenda is the green energy transition with a (belated) interest in methane as a major source of CO2 emissions. Yet the focus should logically be on reducing the whole range of fossil fuels including coal.

Moreover, a major issue was looming at COP 28: the loss and damage fund intended to help developing countries address the climate challenge. Perhaps unsurprisingly, that was the first issue the conference resolved, two days ago, with much fanfare “uniting the world together”. The UAE immediately announced it would commit $100 million to the Fund, paving the way for other nations. And COP President Al Jaber called on nations to follow the UAE’s example.

Other notable commitments reported on that day included $100 million from Germany, £40million from the UK plus some £ 20 million for arrangements other than the Fund, $ 10 million from Japan, and $17.5 million from the U.S. The latter initially modest commitment radically changed after Vice-President Kamala Harris arrived in Dubai, announcing that the US was pledging $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund.

This is no doubt a very good step forward, although adherence to the Fund still depends largely on countries’ goodwill since they don’t need to join the fund because it’s not obligatory. But there’s no denying that the effect of competition may well result in a more desirable outcome as countries may start to try and keep up with the U.S.

Also, and most certainly, at COP 28, the expanded use of fossil fuels is not officially on the table. Yet (and shockingly for climate activists) briefing documents leaked before the conference began, revealed that the UAE intended to discuss fossil fuel projects with representatives of other countries who traveled to Dubai under the auspices of tackling the climate crisis.

At this point, what is a known fact is that the President of COP28 is guiding vast expansion plans for his country’s own oil company. Researchers are shocked and climate activists are enraged: It makes a mockery of the whole COP process.

COP28 is shaping up as a battle royal between countries that want to combat global warming by prioritizing the phasing out of coal, oil and gas and those, like the UAE, that push for scaling up technologies such as carbon capture intended to diminish their climate impact.

How then to define UAE’s political position if not greenwashing of fossil fuels?

Saudi Arabia: “sportswashing” to distract from its human rights record

A few months ago, in July 2023, an exclusive on The Guardian revealed that “Saudi Arabia’s $6bn spend on ‘sportswashing’” through “sports deals since early 2021”. And critics have reportedly labeled this as “an effort to distract from its human rights record”.

What we do know is that in 2018, Saudi Arabia made its first major investment through its Public Investment Fund with a ten-year contract to host World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) events, a deal worth a reported $100 million per year. Since then, Saudi Arabia has made huge investments in golf, soccer, cricket, boxing, tennis, horse racing, and Formula 1 events.

The Saudis have reportedly poured at least $6.3 billion on such endeavors up to 2021 – a scale of such magnitude as to transform many such sports markets. Consider that the $6.3bn investment is almost equivalent to the GDP of Montenegro or the island of Barbados.

The Guardian notes that this level of spending on sports is “at a scale that has completely changed professional golf and transformed the international transfer market for football.” And not just those two sports – as noted above – also other sports such as horse or car racing are affected.

Saudi Arabia’s effort at giving itself a “new face” is that of the world’s largest, deepest-pocket investor/owner in international professional sports. The list of wrongs it needs to cover up needs no reminder: After the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Saudi Arabia was broadly shunned. Add to that its troubled role in the costly Yemen war, characterized by merciless bombing, hurting vast swathes of the civil population.

And if women now can drive cars and fly planes in Saudi Arabia, this hasn’t yet been followed by enough legal, policy, and customary changes to ensure that gender equality is achieved.

Much more still needs to be done. In a survey conducted by Ipsos in 2019, 33% of respondents in Saudi Arabia believed that women having equal access to education was one of the areas where most progress had been made. The areas that still require urgent reform range from political representation (as of February 2021, only 19.9% of seats in parliament were held by women) to a lack of access to assets, a gender pay gap, sexual harassment and violence against women.

Against this backdrop of inequity, the lavish spending on sports appears particularly galling. Rights groups such as Grant Liberty, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have termed such extravagant spending as “sportswashing”.

Can we blame them?

Looking forward

Both countries have carved out a highly visible role to project an image different from that generally held outside the region. The “washing” aspect could be positive if it were followed by genuine change and reform.

This doesn’t appear to be the case so far, but the situation could change if those countries were to start moving toward real democracy, where everyone has a say.

Seeing the power of incredible liquid wealth, we have much to be concerned about.