We’ve all read about forests destroyed by wildfires in Australia and California, illegal logging and deforestation in Indonesia to make space for palm plantations, the Amazon rainforest turning into a savanna. But what about the bigger picture? Should we worry, or can we live in a world with less forest cover?

The answer from the experts is a resounding no. Why? We need the forests we have on this planet precisely the way they are (or even better than they are now) since, among other things, they happen to underpin one of the most popular strategies to combat climate change: Carbon credit markets.

This is a strategy that has been adopted with enthusiasm by a large swathe of economists because it is based on the idea that pollution should be monetized and by conservative neo-liberals because it calls for polluters to buy carbon credits to “balance out” their pollution rather than be taxed for it.

On the political side, the European Union and California were early adopters and leaders in creating carbon credit markets. The American private sector has recently joined in and set up carbon credit trading, so-called voluntary carbon markets (VCMs). Some notable carbon credit exchanges emerging in the US include CIX (Climate Impact X), Carbonplace, and CTX (Carbon Trade eXchange). The Biden-Harris Administration has emphasized the importance of “high-integrity VCMs,” meaning these markets should be designed to support decarbonization efforts by ensuring that carbon credits represent real, additional, and lasting emissions reductions.

“Real, additional and lasting” is a tall order for carbon credits in the face of shrinking forests. A shrinking that has three main causes: global warming, deforestation and wildfires. The collapse of forests not only accelerates climate change, it also threatens the so-called carbon offset projects that underpin the emission of carbon credits. And that is the issue here.

When forests collapse, carbon credit markets are undermined

Unsurprisingly, examples of carbon credit markets negatively impacted by the shrinking forests underpinning them are multiplying.

The Amazon rainforest is particularly at risk. In Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, deforestation and forest degradation have undermined several carbon credit projects. A 2023 Cambridge University study found that over 60 million carbon credits came from projects that barely reduced deforestation, if at all. Of a potential 89 million credits from these offset schemes, only 5.4 million (6%) were linked to additional carbon reductions through preserved forests.

Another worrying example is the one unearthed by a 2023 study in the journal Science reporting that many REDD+ projects in the Amazon have overestimated their impact, with some even leading to increased deforestation.

This news is a warning that we shouldn’t ignore precisely because of what the REDD+ programme stands for. To recall what REDD+ means: Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries. The programme was developed under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2008. The “+” in REDD+ signifies the inclusion of conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks.

REDD+ has been successful in raising global awareness about the importance of forests in mitigating climate change and has achieved wide coverage in developing countries, with some 1.35 billion hectares of forest and 17 countries reporting a reduction of 11.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide.

This said it’s not all roses. The problem is deforestation. When a REDD+ project relies on maintaining existing forest cover to achieve its goal, then it is at risk of obvious failure when the trees die or are cut down: The carbon they store is released, undermining the projects’ ability to offset emissions.

The deforestation of palm oil plantations and, more generally, illegal logging have also led to significant forest loss in Southeast Asia. This has impacted carbon credit projects in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia. For instance, peatland forests in Indonesia, which store vast amounts of carbon, are being cleared and drained, leading to substantial greenhouse gas emissions and undermining the effectiveness of carbon offset projects in the region.

Africa is also concerned. For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) carbon credit projects designed to protect tropical forests have faced challenges due to deforestation driven by logging, mining, and agricultural expansion.

Wildfires are as devastating as logging and equally damaging to carbon credit schemes.

For example, in California, wildfires have released huge amounts of stored carbon, jeopardizing forest carbon offset projects in the state. For example, a 2016 wildfire burned a large portion of a project area in the Klamath Mountains, releasing an estimated 3.8 million tonnes of CO2 and raising questions about the long-term viability of such projects in fire-prone areas. A recent study examining, inter alia, the Klamath Mountains region between 1986 and 2017 found that wildfires have lasting effects: There is an immediate post-fire warming effect, and it takes at least 25 years for a land area to recover.

And, of course, we have the example of Australia. The devastating bushfires in 2019-2020 in Australia highlighted the vulnerability of forest carbon projects to extreme events. Millions of hectares of forest burned, releasing significant amounts of carbon dioxide and raising concerns about the ability of these projects to deliver reliable carbon offsets in the face of increasing climate risks.

It is crucial to address these issues and develop more resilient and effective strategies for forest conservation and carbon mitigation.

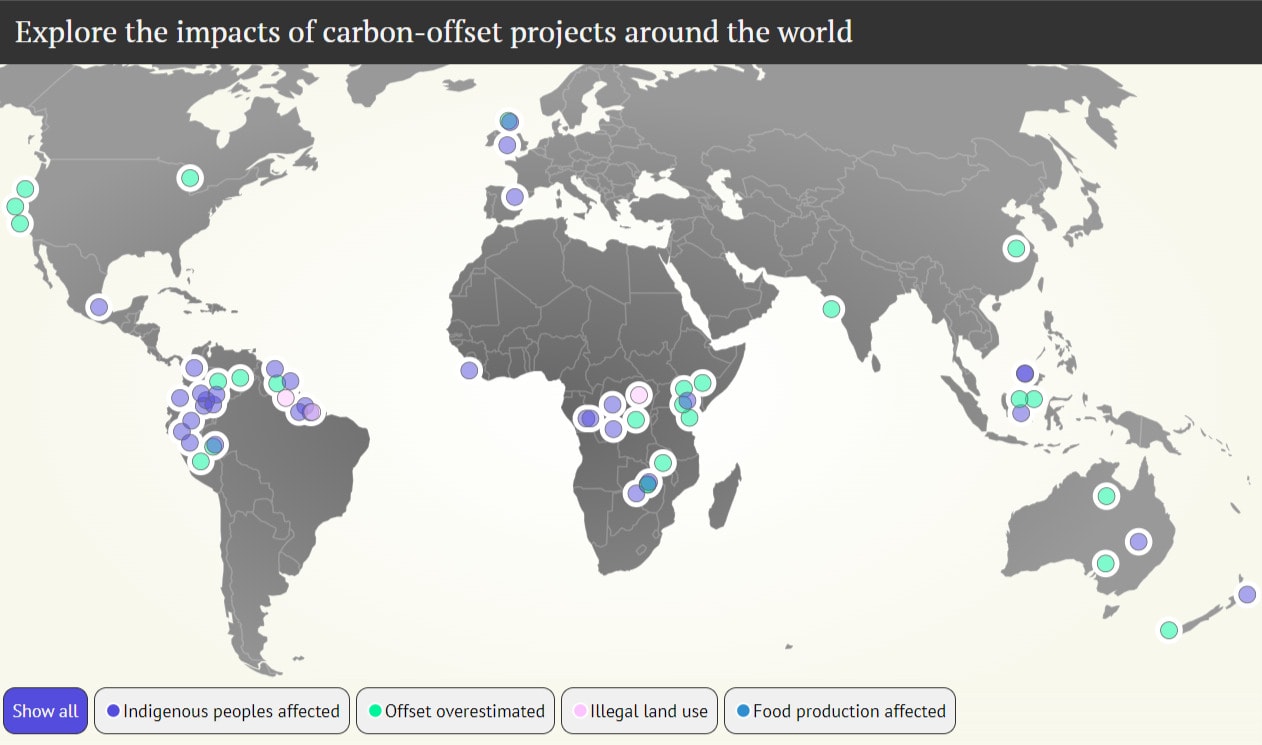

Here is a map prepared by Carbon Brief of all the main carbon-offset projects around the world:

This map offers information on each of these 61 carbon offset projects. On the map, dots represent individual carbon-offset projects, with:

- purple indicating harm to Indigenous peoples and local communities,

- green indicating the ability to offset emissions being overestimated,

- pink indicating illegal land use and

- blue indicating food production being affected.

Some 72% of the reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects causing harm to Indigenous peoples and local communities. And 43% of the reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects overstating their ability to reduce emissions.

The bigger picture: Carbon sinks are disappearing

The issue of forests becoming less effective carbon sinks is a global one with potentially dire consequences. The overall trend is worrying. As forests face increasing pressure from human activities and climate change, their ability to absorb our carbon emissions is diminishing. This creates a dangerous feedback loop, where rising emissions lead to further forest decline, which in turn releases more carbon.

Finland’s Case: This is the most recent and alarming case. Data indicates that its forests are now releasing more carbon than they absorb, primarily due to factors like:

- Increased logging: Finland’s forestry practices have intensified, leading to younger forests that store less carbon.

- Warming temperatures: Rising temperatures accelerate decomposition of organic matter in the soil, releasing more CO2.

- Increased tree mortality: Pests and diseases, exacerbated by climate change, are causing more trees to die and release their stored carbon.

Finland is unfortunately not alone. Boreal forests everywhere are under siege.

In Europe: The overall picture in the EU is still positive, and EU policies promote sustainable forest management practices to ensure the long-term health and carbon sequestration capacity of forests. Fine and good. Still, the problems noted in Finland have in one form or another emerged elsewhere in Europe.

While forested areas have been relatively stable, the health and vitality of these forests are declining. Already in 2011, the BBC reported that many EU forests were nearing a “carbon saturation point.” This refers to the issue of nitrogen saturation, whereby forests can no longer absorb more nitrogen from the atmosphere and soil. This can lead to soil acidification, nutrient imbalances, and decreased tree growth.

Related Articles: Will International Carbon Markets Finally Deliver? | The Voluntary Carbon Market: Unregulated and Useless?

Today, while deforestation is not a significant issue in Europe, its forests are under significant pressure from other causes linked to climate change, as evidenced in the report State of Europe’s Forests.

For example, Germany, which has a high forest cover (about 32% of the land area) and actively manages its forests, is experiencing increasing stress from climate change, with drought and bark beetle outbreaks causing significant damage in recent years, particularly to spruce forests. And air pollution remains a concern in some areas. Similar problems affect forests in central and eastern Europe.

Boreal forests in the Northern Hemisphere, including regions like Alaska, Canada, and Russia, have seen a 36% decline in their carbon sink capacity. This is largely due to increased disturbances from wildfires, insect outbreaks, and soil warming.

Similarly, tropical forests in the Amazon and Africa are also losing their ability to sequester carbon. Higher temperatures and stronger drought conditions, which are symptoms of global warming, are slowing plant growth and increasing tree mortality.

This has been observed in long-term records from regions like Borneo, where tree mortality increased significantly after the 1997-1998 El Niño drought. In addition, peat swamp forests have turned into net carbon sources over the last few decades due to peat decomposition from drainage for agricultural activities.

The way forward

The study titled “The enduring world forest carbon sink,” published in the 18-July-2024 issue of the journal Nature, highlights the critical role of forests in mitigating climate change. The study further shows that deforestation and disturbances like wildfires are threatening this vital carbon sink.

To sum up where we stand now: There is no question that the world’s forests continue to be a powerful weapon in the fight against climate change. And a decline in forest carbon sinks has serious consequences:

- Accelerated climate change: Less carbon absorption by forests means more CO2 remains in the atmosphere, further warming the planet.

- Reduced biodiversity: Forest degradation and loss threaten countless species, disrupting ecosystems and their vital services.

- Impacts on local communities: Forests provide livelihoods and resources for many communities. Their decline can have devastating social and economic consequences.

What can be done? Addressing this issue requires a multi-faceted approach, one that we know only too well by now, namely:

- Protection of existing forests: Reducing deforestation and forest degradation is crucial.

- Sustainable management of forestry resources: Implementing practices that promote carbon storage and forest health.

- Reforestation and afforestation: Planting new trees to increase carbon sequestration.

It all comes down to a single requirement: Reduce emissions. Ultimately, we need to drastically reduce our reliance on fossil fuels to curb climate change and its impacts on forests.

The situation is serious but not hopeless. By taking urgent action to protect and restore our forests, we can help maintain their vital role in mitigating climate change. And by the same token, ensure that carbon credit markets are, in fact, “high integrity VCMs” and are indeed providing a “real, additional and lasting” reduction in carbon emissions.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: Forest fire in Demre, Türkiye. Cover Photo Credit: Yavuz Solgun.