We know about the moon and space more than we know about the value of services and support the ocean provides to humankind.

To help drive a new collective consciousness on interdependencies between the life on land and the ocean, as well as its resources, we need a multidisciplinary approach. It is crucial to encourage context-specific communication approaches, develop innovative research tools and, finally, build informed consensus on further action.

In December last year, this was the reason I travelled from the bustling city of Lagos, through Istanbul, to Venice for the International Ocean Literacy Conference, hosted by the UNESCO Regional Bureau for Science and Culture in Europe with financial support from the Swedish Ministry of Environment and Energy. Though I must admit, I also wanted to experience The Floating City’s culture and food.

Being the only Nigerian and undergraduate, as well as the youngest at that conference allowed me to clearly understand the role and expectations of young people and students in the global ocean agenda.

IN THE PHOTO: Peter Pissierssens (UNESCO/IOC), Vladimir Ryabinin (UNESCO/IOC), Gesine Meißner (EU Parliament), and Peter Thomson (UN Special Envoy for the Ocean) take questions during a High Level Panel at the International Ocean Literacy Conference, Venice. CREDIT: UNESCO Venice Office

The health of our ocean, seas, rivers and other marine resources are at risk primarily because of us, humans. Our activities put marine systems in danger. Although the terrible consequences of these doings will be felt in the whole world, its catastrophic impact will hit young people the hardest. For example, my country, Nigeria, has over 450 miles of coastline, centrally located in the Gulf of Guinea. But this diverse, marine domain is now endangered, facing sharp conservation challenges and threats: overfishing; plastic, soot and oil pollution; and targeted poaching of its five sea turtle species. In the future, young people and students will be the leaders here. And they will face the inevitable effects in greater force.

Four in ten people of the world’s population live near the ocean. In low-lying coastal areas, such as cities in small island countries, the resulting consequences of human-caused marine degradation and climate change are already visible: sea-level rise is now exacerbating surface floods, storm surges, and coastal erosion, thus not only destroying infrastructure and homes but also disrupting lives and livelihood.

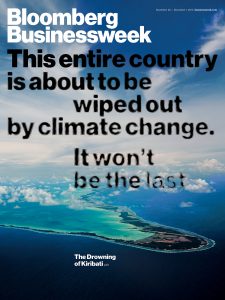

Take Kiribati, for example. Following severe flooding events there – that even infiltrated freshwater, making it undrinkable– scientific community predicts the South Pacific nation will be underwater in 30 to 50 years. So affected I-Kiribati people keep moving to other habitable parts. Thinking in the long-run, the government adopted a policy of migration with dignity by buying a piece of land in Fiji. These distressing realities are particularly striking when you listen to former President of Kiribati, Anote Tong, talk to Leonardo DiCaprio, a Hollywood Actor and UN Messenger of Peace on Climate Change:

I’ve got grandchildren. I’ve got 12 grandchildren. I’d like to be able to, to go away knowing that they will continue to have a home.

The rights of young people and all future generations to a safe Earth made habitable by the water, oxygen, nutrients and climate-regulating capability provided by the ocean, are abused.

IN THE PHOTO: Kiribati, the first country likely to be swallowed by the rising seas. CREDIT: Bloomberg Businessweek

Here’s one of the most tremendous, revealing pointers we have to face: fresh science-based solutions, which will direct and inform policies and decisions, are crucial in achieving the targets of Global Goal 14 (Life below water). Young people, dedicated to studies and evidence-based research are powerful forces required for this task. In short, all roadmaps for an ocean revolution – having the ocean we need for the future we want – need to value and include undergraduate students from ocean science courses.

Perhaps, understanding that this is actually one brave matter takes the potentials of science to resist broader ocean issues and sustainably grow the ocean economy well beyond the starting point of this revolution.

When thinking about one of the questions asked at the Conference in Venice, “Who do we still need to engage?” I suddenly realised how simple the answer was: developing university systems. Note that universities are not just the world’s oldest capacity-building institutions, they are also learning and character-developing hubs for the next generation of scientists who will bring a fresh wave of breakthroughs and discoveries. Therefore, bigger stakeholders within the ocean community should seek to reduce knowledge and capacity-developing divides between the marine industry and students of developing universities offering marine science and technology degrees. Approach for this effort ought to be deliberate and have glocal themes and be exchange-based (knowledge, experience, research and immersion visits, or expertise). That way, young people and students are given a voice.

IN THE PHOTO: Ambitious to save Kiribati atolls and its people from sea-level rise and storm surges? CREDIT: DFAT/Erin Mageeiribati

Below is an example of successful implementation of this idea. Danilo Calazans from Universidade Federal do Rio Grande wrote about his best Ocean Science experience in “Ocean Literacy for All. A toolkit” – a two-volume manual produced by UNESCO’s Regional Bureau for Science and Culture in Europe (Venice, Italy) and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, and newly released during the Conference too.

“The active participation of students from Oceanography courses on research cruises in Brazil was usually restricted, since the few extra spaces available were occupied by researchers, technicians and scholarship students directly involved with the work to be performed. The requirement of an on-boarding experience for the completion of Oceanography courses was introduced in 1989. Since then, among other requirements, students must complete 120 hours on board. In 1996, the Oceanology Course Commission of Federal University of Rio Grande – FURG created a discipline: “Oceanographic Techniques and Equipment Practices,” with the objective of “preparing the students to get experience on oceanographic data collection, analysis and how to observe abiotic and biotic aspects during a cruise aboard a research vessel that would serve as an advanced oceanography laboratory… I participate actively in a Ministerial commission to find ways to promote student’s participation in oceanographic cruises. Four new vessels are being built by the Ministry of Education. They are the Floating Teaching Laboratories, which will on-board students from all over Brazil.”

That’s not all. Emily King from Xiamen University, People’s Republic of China, adds, “For those of us working in education, especially environmental education, we will not know if our efforts have been truly successful till after we are gone, as it’s the actions of subsequent generations that are a measure of our success or failure. But moments like [these] help keep me motivated and hopeful for the future.”

IN THE PHOTO: Formal Education Conference Working Group brainstorming posers, including “Who do we still need to engage?” CREDIT: UNESCO Venice Office

Yet, in some parts of the world, like my country, the undergraduate is barely seen as a knowledge producer or basic researcher, especially in fields like Earth science. There is a predominant idea that the job of devising and using novel ways to engage ocean threats and industries is limited to scientists and technologists in private and public sectors. Undergraduate students and other young people should be recognized as important partners at the table, and as discoverers, in the generation of promising new technologies and new horizons of scientific knowledge about the ocean. We are empirical-minded too, and when given a fair chance of inclusion and support, we can buckle-down, get radical, source data, out-innovate, and actively report our findings in interdisciplinary conversations! All from a unique, millennia’s perspective!

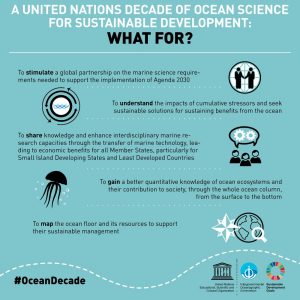

In the lead up to The International Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development – a coherent cooperation framework that will focus on designing scientific and technological solutions to boost biodiversity knowledge and make our impact on the ocean sustainable – bigger stakeholders and institutions ought to seize this open opportunity. We have the capacity to help close data and knowledge gaps and we want to contribute to safeguarding our tomorrow before it is too late.

IN THE PHOTO: Launched at Venice – Ocean Literacy for All. A Toolkit. CREDIT: UNMGCY/Oghenechovwen Oghenekevweo

I want to protect the ocean. And I believe one must take part in creating the desired future. CEO and Founder of Action GX, Oluwatoyosi Bakare, and I are developing an idea to pilot and co-organize debates and structured dialogues across five Nigerian universities offering degrees in Earth sciences on specific ocean topics and intersections with sustainable development. Featuring academicians and industry experts, we are optimistic it will offer an innovative and engaging way to address issues and reduce divides between “research” and “stakeholder”. We seek to stimulate critical reflection and well-informed conversations amongst 500 undergraduates and other learners, encouraging them to tackle local environmental, marine and climate challenges.

IN THE PHOTO: What the UN Decade of Ocean Science aspires to? CREDIT: CLIVAR/Jing Li

FEATURED PHOTO: Ocean and Climate Youth Ambassadors of Peace Boat’s 95th Global Voyage share how climate change and marine degradation affect their communities. CREDIT: Peace Boat/Neil Murphy

Editors note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com