EDITOR’S NOTE: THIS PIECE IS AUTHORED BY SAVIO CARVOLHO, A SENIOR ADVISOR OF AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL. THIS PIECE IS PART OF A SERIES EXPLORING THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS. SEE THE INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES HERE. THIS PIECE IS AUTHORED BY SAVIO CARVOLHO, A SENIOR ADVISOR OF AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL.

Many have referred to 2015 as a historic year for people, planet, and prosperity — for it was in this year that Member States (our governments) agreed on addressing some serious challenges faced by the present and future generations. I guess this is true, especially for those involved in these negotiations, but for the rest of the world, which is the majority, it was and continues to be business as usual.

The so-called historic year 2015 had the culmination of three major processes at the United Nations:

1. the financing for development summit in Addis Ababa

2. the special summit on Sustainable Development Goals in New York, adopting the 2030 Agenda, with its attendant 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and related 169 targets

3. the Climate Change Conference of parties in Paris. These three major UN processes or tracks, each supposedly feeding into each other, would hopefully result in a radical and transformational change

It is worth noting that these processes reaching their climax were a result of many years of negotiations, differences, politicking, and failures. At the same time, these processes also saw an unprecedented level of participation, pressure and call to action from the public at large.

Having being involved in two of the three processes at different moments in history, I can say with a high degree of certainty that real appetite for change and transformation was more often than not sacrificed at the altar of sovereignty, selfishness, greed, and a myopic perspective. Sadly, this seems to become the norm in most intergovernmental processes at the UN.

A few years ago, global civil society campaigned for a FAB (Fair, Ambitious, and Binding) climate change deal at the Copenhagen conference of parties. Civil society across the globe spent over two years creating awareness, mobilizing the public, parliamentarians, and the media for a FAB deal. Alas, to our utmost disappointment, there was lack of agreement among member states, and thus the Copenhagen conference outcome was a greenwash.

In 2010, a high-level plenary meeting of the UN General Assembly was held on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This summit was to take stock and build momentum to achieve the MDGs over the last few years. The summit also set the works in motion to develop a post-2015 agenda.

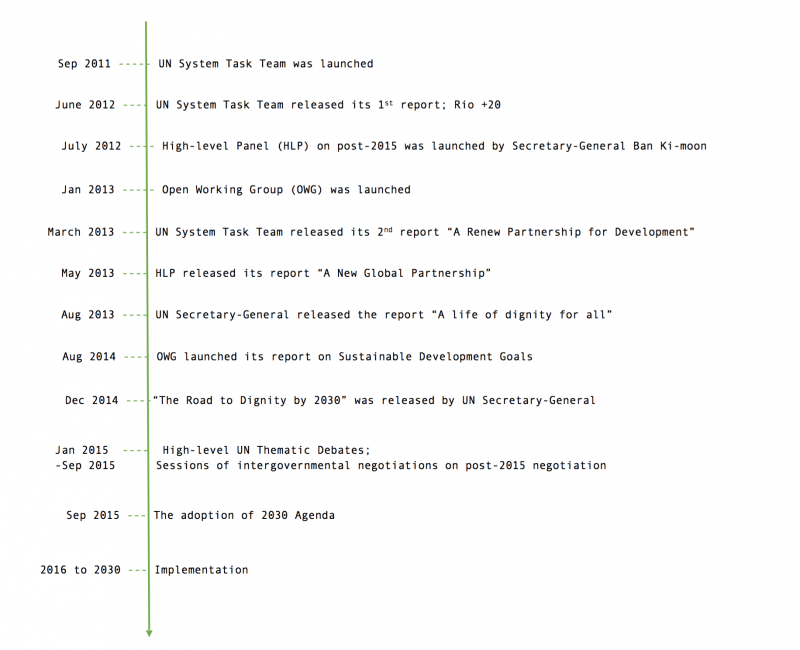

Following on the outcome of this high-level plenary meeting, the UN Secretary-General established the UN System Task Team in September 2011 to support UN system-wide preparations and released its first report, “Realizing the Future We Want for All” in June 2012.

They identified four core dimensions for sustainable development:

- inclusive social development;

- environmental sustainability;

- inclusive economic development and

- peace and security.

Their second report “A Renewed Partnership for Development,” released in March 2013, stated the need for a revitalized global partnership for development for the post-2015 era as well as reflecting the increasing importance of other stakeholders such as civil society.

One could see attempts being made to learn lessons from the MDGs in the development of the post-2015 agenda.

Photo Credit: Press Briefing by Representatives of Amnesty International & Human Rights Watch. A member of the UNCA Press asked questions to panelist of Amnesty International & Human Rights Watch re: Saudi Arabia’s violation of Human Rights in Yemen. Loey Felipe, UN Photo, UN Media Archive

Critique of the MDGs

In the early part of the new millennia, when working in Tajikistan, I came across some concerted efforts to align the work of local and international NGOs, donors, and UN agencies to the MDGs.

At the field level, we had little information or reasoning for this push to deliver the MDGs. It seemed like a classic case of a top-down approach. From a field perspective, it looked a bit strange but not an impossible task to show on paper how our work was aligned to the MDGs, yet there remained many unanswered questions on the goals, how they were decided, and why they were being pushed down without any consultations.

Whilst the MDGs did raise the profile and resources for issues like poverty eradication, maternal mortality, education, they fell short of using or reinforcing human rights as an approach to development.

In fact, it can be said that the MDGs resulted in quite the opposite. There were potential human rights violations in the name of achieving the MDGs.

For example, according to data from the United Nations Development Programme, Nigeria made progress on nearly all of the MDGs goals. Yet these top-line figures mask regional differences, inequalities, and disparities between various groups and minorities. In just one Nigerian city, more than 200,000 people faced eviction because the authorities demolished several informal settlements in Port Harcourt’s waterfront area. Yet such actions could also be interpreted as meeting an MDG target to halve the proportion of population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

The story is similar in many other countries. As Amnesty International’s evidence shows, forced evictions are taking place across the world. In Europe, many cases are leading to the segregation of Roma communities. Across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, tens of thousands have also been forcibly evicted from traditional lands to make way for multinational extractive industries and agri-business.

Related article: “A PLATFORM FOR A NEW ERA OF INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION”

How did we move from MGDs to SDGs?

At the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), held in Rio de Janeiro in June 2012, Member States agreed to launch a process to develop a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Rio+20 did not elaborate specific goals but stated that the SDGs should be limited in number, aspirational, and easy to communicate.

This process was led by the member states themselves who wanted to be in the driving seat and not repeat the mistakes of the MDGs which had a top-down approach.

Based on the negative experiences of the MDGs, civil society organizations were alert on the processes leading up to the post-2015 agenda. Many were supported by donors and philanthropic organisations to get involved in the process leading up to the post-2015 agenda. At Rio+20, the human rights community positioned itself with a sole purpose: bring human rights to the core of the new agenda. Be it the impacts of mining on indigenous lands, extraction of fossil fuels, communities displaced due to flooding or soil erosion, or climatic changes leading to drought and food insecurity, they all have implications on human rights of individuals and communities. The rights of the present and future generations were also at stake. And all this related to obligations of governments to take urgent steps to stop actions of state and non-state actors leading to direct or indirect violations of human rights. Finally, governments were also expected and responsible to monitor and regulate the actions of corporations beyond their own borders.

The Rio+20 summit created a groundswell for human rights to be at the centre of any new developmental agenda.

How did we get this agenda

The lead up to the new agenda was full of many processes, many of which were running in parallel. Whilst I shall not go into each of them, I will speak of a few from my own experience.

The UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon launched a High Level Panel on Post 2015 Development Agenda consisting of 27 representatives from civil society, private sector, academia, and local and national governments. The work of the panel reflected new development challenges while drawing on experience gained in implementing the MDGs, both in terms of results achieved and areas for improvement.

At an international civil society organizations (CSO) meeting in Bonn, after a briefing from some members of the High Level Panel, it became clear that the panel was not going to live up to our expectations of making bold recommendations, with human rights at the core of the new agenda.

In response, over 300 CSOs issued a red flag statement highlighting a few non-negotiables called “red flags,” which civil society would like to see in the final report. This for me was a big milestone of a coordinated effort in terms of influencing the agenda.

The panel did take a few our recommendations on-board and submitted its report “A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economics through Sustainable Development” in May 2013, calling for five transformational shifts:

- leave no one behind;

- put sustainable development at the core;

- transform economics for jobs and inclusive growth;

- build peace and effective, open and accountable institutions;

- forge a new global partnership.

In parallel, a 30-member Open Working Group (OWG) of the General Assembly was tasked with preparing a proposal on the SDGs. This process stretched over several months, giving time for inputs, feedback, critiques, and engagement of civil society.

Civil society organizations from all over the world had an opportunity to make their voices heard during the negotiations. We had both the co-chairs committed to keeping the process open, transparent and engaging. CSO representatives made formal interventions, read statements, issued warning letters, lobbied member states, and used a raft of tactics to get their points across and be heard. A “Report of the Open Working Group on of the General Assembly Sustainable Development Goals” was released in August 2014. This report became the starting point of the intergovernmental negotiations which concluded a year later with the adoption of the 2030 Agenda.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #SDGStories

Is Agenda 2030 human rights friendly?

If we take the MDGs as a baseline, then we could say with confidence that the 2030 agenda has come a long way. If we continue on this line of argument and say that the MDGs were devoid of human rights, then what we have in the 2030 Agenda is good but not good enough.

A number of major human rights elements were included in the language of the SDGs, as detailed in the box below.

|

The Human Rights Elements in the 2030 Agenda |

In para 3: “We resolve, between now and 2030, to end poverty and hunger everywhere; to combat inequalities within and among countries; to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies; to protect human rights and promote gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls; “ In para 8: “We envisage a world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity, the rule of law, justice, equality and non-discrimination; of respect for race, ethnicity and cultural diversity; and of equal opportunity permitting the full realization of human potential and contributing to shared prosperity. In para 9: “We envisage a world (…) in which democracy, good governance and the rule of law as well as an enabling environment at national and international levels, are essential for sustainable development, including sustained and inclusive economic growth, social development, environmental protection and the eradication of poverty and hunger. “ Para 10: “The new Agenda is guided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, including full respect for international law. It is grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, international human rights treaties, the Millennium Declaration and the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document. It is informed by other instruments such as the Declaration on the Right to Development.” Para 19: “We reaffirm the importance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as other international instruments relating to human rights and international law” |

The preamble starts with “This Agenda is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom.“ Para 34: Sustainable development cannot be realized without peace and security; (…) we must redouble our efforts to resolve or prevent conflict and to support post-conflict countries, including through ensuring that women have a role in peace-building and state-building. “ |

“(…) As we embark on this collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind.” Para 13: refers to inequalities within and among countries: “Sustainable development recognizes that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, combatting inequality within and among countries, preserving the planet, creating sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth and fostering social inclusion are linked to each other and are interdependent.” Para 19: “We emphasize the responsibilities of all States, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations, to respect, protect and promote human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, disability or other status.” Para 23: “People who are vulnerable must be empowered. Those whose needs are reflected in the Agenda include all children, youth, persons with disabilities (of whom more than 80% live in poverty), people living with HIV/AIDS, older persons, indigenous peoples, refugees and internally displaced persons and migrants.” |

[The SDGs] seek to realize the human rights of all and to achieve gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls. Para 11:” We reaffirm the outcomes of all major UN conferences and summits (…) the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, the Beijing Platform for Action; and the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (“Rio+ 20”). (…) Para 20: “Realizing gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls will make a crucial contribution to progress across all the Goals and targets. The achievement of full human potential and of sustainable development is not possible if one half of humanity continues to be denied its full human rights and opportunities.” |

Para 24: “We are committed to ending poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including by eradicating extreme poverty by 2030. All people must enjoy a basic standard of living, including through social protection systems.” Para 7: “A world where we reaffirm our commitments regarding the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation and where there is improved hygiene; and where food is sufficient, safe, affordable and nutritious.” Para 25: We commit to providing inclusive and equitable quality education at all levels – early childhood, primary, secondary, tertiary, technical and vocational training. All people, irrespective of sex, age, race, ethnicity, and persons with disabilities, migrants, indigenous peoples, children and youth, especially those in vulnerable situations, should have access to life-long learning opportunities that help them acquire the knowledge and skills needed to exploit opportunities and to participate fully in society.” Para 26: “To promote physical and mental health and well-being, and to extend life expectancy for all, we must achieve universal health coverage and access to quality health care. No one must be left behind.” Our shared principles and commitments Para 27: “We will work to build dynamic, sustainable, innovative and people-centred economies, promoting youth employment and women’s economic empowerment, in particular, and decent work for all. We will eradicate forced labour and human trafficking and end child labour in all its forms.”

|

Para 45: “We acknowledge also the essential role of national parliaments through their enactment of legislation and adoption of budgets and their role in ensuring accountability for the effective implementation of our commitments.” Para 47: “Our Governments have the primary responsibility for follow-up and review, at the national, regional and global levels…… To support accountability to our citizens, we will provide for systematic follow-up and review at the various levels, as set out in this Agenda and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda.” Para 67: “We will foster a dynamic and well-functioning business sector, while protecting labour rights and environmental and health standards in accordance with relevant international standards and agreements and other on-going initiatives in this regard, such as the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the labour standards of ILO, the Convention on the Rights of the Child and key multilateral environmental agreements, for parties to those agreements.” Para 73: “Operating at the national, regional and global levels, it will promote accountability to our citizens, support effective international cooperation in achieving this Agenda and foster exchanges of best practices and mutual learning” Para 74. (e.) Follow and review… “They will be people-centred, gender-sensitive, respect human rights and have a particular focus on the poorest, most vulnerable and those furthest behind.” |

Accountability for delivery of Agenda 2030

Agenda 2030 can be compared to a see-saw with ambition of agenda and accountability sitting on opposite side. Although this agenda is not legally binding, a strong monitoring and accountability framework would have given it the much needed lifeline for success. At times it seems like the ambition of Agenda 2030 is inversely related to monitoring and accountability. Civil society and a few member states made persistent calls for greater accountability in implementation and delivery at the global, regional and national level, albeit with limited success.

What is the use of such a bold and ambitious agenda if no one is going to be held to account for its timely delivery for transformational change?

In the run-up to the SDG summit of 2015, unprecedented level of resources were spent by governments, donors, CSOs, philanthropic organisations, and the private sector to participate, influence the process, content and final outcomes of the post-2015 agenda. It begs belief that such vast amounts of resources, mainly from the tax payers purse, were used for a political declaration, with only a sprinkle of follow-up and review mechanisms included in the overall architecture , all of which is voluntary in nature.

The human rights caucus, an informal collective of many rights-based organisations across the world, proposed an inbuilt mechanism to strengthen accountability in the post 2015 agenda. This was based on the working methods of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) and the Africa Peer Review Mechanisms whereby Member States would be reviewed by their own peers with each member being reviewed once every 4-5 years. It was proposed that civil society and other stakeholders would be able to participate and contribute to such a review process. Not surprisingly, there was very little pick up for such proposals or anything which might bind member states to be reviewed.

To our disappointment, even the word “accountability” was carefully substituted with “follow-up and review.”

Another smoke screen was the lack of accountability of the private sector who are considered as a “key partners” in the delivery of the 2030 Agenda.

While welcoming investments, civil society once again advocated for in-built mechanisms to ensure that the 2030 Agenda would provide adequate safeguards for individuals and communities against corporate crimes and abuses, as they deliver sustainable development. Only a few member states supported this call, but the vast majority were not in favor of pushing back investments or demonizing the private sector.

Photo Credit: UNPOL and FPU prepare for the arrival of the delegation at the POC site in Bentiu when United Nations Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights visits South Sudan. JC McIlwaine, UN Photo, UN Media Archive

It is also worth noting that even though this agenda is adopted by all member states, many of them have added caveats, known as “reservations” in the UN parlance. These reservations are on specific text or language which the respective member states will not be delivering on and can’t be held accountable for. One may question, when this is not a legally binding instrument, why go this far in making reservations.

In addition to reservations, the agenda also seems to make allowances under the guise of national circumstances:

“The SDGs and targets are integrated and indivisible, global in nature, and universally applicable, taking into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development and respecting national policies and priorities. Targets are defined as aspirational and global, with each government setting its own national targets guided by the global level of ambition but taking into account national circumstances .”

Whilst appreciating the one-size-does-not-fit-all principle, there is a strong case for the agenda to be flexible depending on some national circumstances. This being the case, there are some minimum core obligations expected of all governments regardless of this agenda. States are legally bound to show that they are taking the right steps in relation to social, economic, and cultural rights. They need to show that they are using the maximum resources available at their disposal for progressive realization of rights. The only challenge with this legal ask is that it is not time bound.

Thus if states have the political will, they can use the time frame set in Agenda 2030 and develop clear work plans to ensure the meet both their legal obligations and at the same time achieve all the goals and targets set out in the 2030 agenda.

Civil society needs to be vigilant and keep its finger on the pulse, as there is a danger that some governments will dodge the goals and targets and even backslide on their legal obligations under the guise the national circumstances or lack of resources.

Where do we go from here…

We are still in the first year of this 15-year long journey for people, planet, and prosperity. Having been closely involved before, during after the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, we must use this framework as an additional tool for transformation, prioritization of resources and concrete movements from policy to practice.

This framework definitely has the potential for change and addresses some (not all) of the major challenges facing our world today.

One aspect of the 2030 Agenda and of the Paris Climate Change agreement is the interconnectedness with climate. This is something new. All our work, across sectors will be futile if we do not link and tackle the issue of climate change. As mentioned by others, this is one area where we neither have a plan B or planet B.

Time is not on our side.

The action of one individual or country is useful but inadequate for any seismic and impactful change. We can’t continue without questioning the current paradigm of economic development. We need to move towards a more carbon neutral economy and sustainable life style. This needs urgent political will for action, especially among countries that have already consumed many times over their share of the carbon space.

Photo Credit: A timeline of SDG development. Savio Carvalho

The strength of this agenda also lies in its universality.

No matter where you are in the development spectrum, we are all developing nations. No nation, state, or peoples are fully developed, and there is always room for improvement. Each state needs to see themselves as a developing nation and embrace this agenda, especially at the domestic level. National policies, priorities, and foreign policies (aid, trade, and climate to name a few) must be docked together with the SDG framework and the Paris agreement. Financing for development moving beyond official development aid (ODA) targets becomes an essential ingredient for success.

Interconnectedness of the agenda is the key element. The goals and targets weave through each other forming a web, a cohesive approach for transformation and change. Prioritization is not a problem, as long as the interconnectedness is the thread that weaves it together.

Another critical element which stands out is “leaving no one behind” – This has already become a buzz statement. If we look around, we do see individuals, communities, and countries left behind as a result of unfair policies, economic systems or discrimination on various grounds. Addressing inequalities in all its forms, making small beginnings, and not letting it slip any further is mission critical for transformation, development, equality, and social justice.

And this takes me to a human rights approach. We have seen that the SDG framework is relatively strong in making direct references to human rights. We need to reap harvest of this language by using existing human rights instruments and monitoring mechanisms to complement the delivery, monitoring, and review of the agenda. Peaceful societies, rule of law, and good governance are also essential ingredients for creating enabling environments.

Finally, it is all about the participation of people, citizens, individual, and communities in the planning, implementation and review of the framework. We do need to work with other non-state actors, social movements, trade unions, human rights defenders, and social activists. We need to forge new connections, redefine the social contract, and hold those in authority to their duties. It is only by doing this will be able to transform our world, our peoples, and our destiny.

Recommended reading: “ CONGRESS PLAYING POLITICS ON AMNESTY“

—