Much of the financing attention in terms of developing countries at global level has been on the role of the international financing institutions in debt forgiveness, substantial new funding made available to governments and their institutions. For example, direct COVID financing has been very significant with provision to COVAX for vaccines, assistance for health systems to cope with new challenges, money to deal with critical shortages, and a host of largely public sector efforts or those mostly channeled through them. All worthy efforts.

What has not gotten much media attention is a major pillar in development thinking, namely efforts directed at the small entrepreneur or farmer, with modest loans for the purpose of explicitly providing needed funds for them to prosper, or at least, survive.

It is worth looking into microfinancing as a key aspect of development, to consider how both Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) and intermediary entities have addressed distressed clients when hit either directly by COVID, or indirectly as the services they rely on or markets have dried up, and how these clients have performed.

How the DFIs generally address the financing of small entrepreneurs

DFI approaches to microfinancing have been evolving, transiting initially from direct investments in projects to more funding through intermediaries, recognizing that smaller providers of microfinance are an important channel of funding for poor and vulnerable communities.

The independent “Consultative Group to Assist the Poor” (CGAP), has done seminal research in this area, finding that during the COVID pandemic some DFIs have offered relief to the microfinance sector either through deferring payments owed to them by the financial intermediaries in which they have invested or through the establishment of new liquidity facilities aimed at mitigating the impact of the pandemic on their operations.

Examples include local currency facilities and equity financing options from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group, the European Investment Bank (EIB), and the Dutch government MASSIF Fund, each having local currency and equity financing options. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is also active in this space as is the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (USDFC) and Germany’s KfW Development, each of which has connections to donors that could provide backup funding to help mitigate risks (such as through the establishment of guarantees for local currency-denominated loan portfolios), and could cover the costs of putting in place solvency-related facilities.

There are also resources from the European Investment Bank (EIB) under the EIB’s African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) Microfinance facility and the BlueOrchard COVID-19 Emerging and Frontier Markets MSME Support Fund. Additionally, there is the DFI- and EU-supported European Fund for Southeast Europe (EFSE) which offers local currency lending

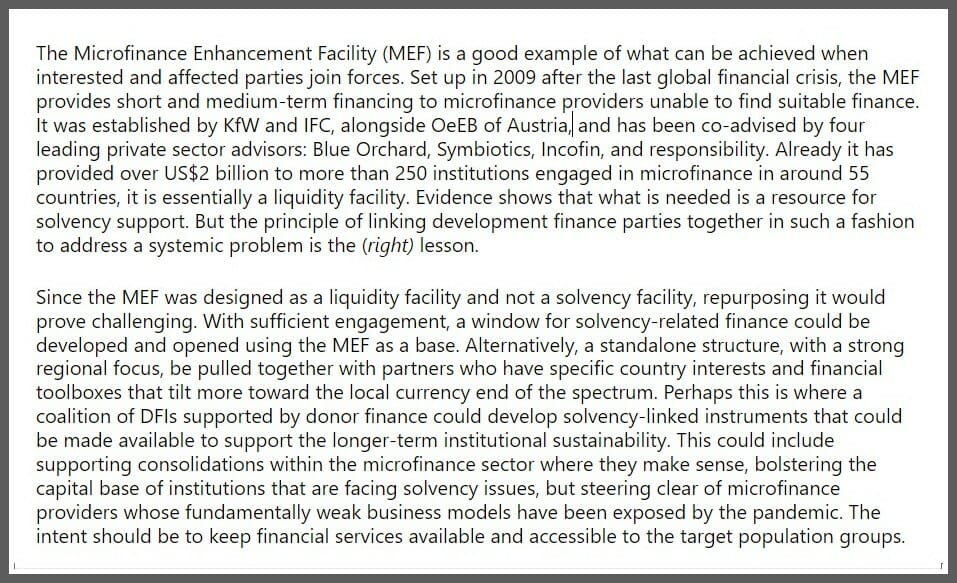

Further, there are windows and avenues available to specific countries for microfinancing and alleviation. A broad approach is the Microfinance Enhancement Facility (MEF), essentially a liquidity mechanism that does not offer at present solvency support.

The CGAP Box below describes what MEF does and does not do:

The COVID impact analysis by CGAP, MFR and Symbiotics offers some hope while highlighting the relative vulnerability of smaller institutions. In many markets, smaller microfinance institutions are challenged in dealing with the shock of non-repayment in an environment of dampened growth amid economic uncertainty.

As CGAP puts it “The full impact of the crisis on the microfinance sector is yet to be felt.”

While fears of a liquidity crisis in the microfinance sector have not yet materialized, the pandemic has placed significant pressure on many microfinance providers and their customers, and it is ongoing. Continued stress on microfinance customers and the credit quality of microcredit portfolios indicate that a solvency crisis may be looming. The sector should take steps now to prepare for that eventuality.

Microfinancing for the small rural farmer/ entrepreneur

The Grameen Crédit Agricole Fondation (GCAF) promotes entrepreneurship alongside the Grameen Bank, which is focused on community development through small loans to the impoverished, with many of its borrowers that are women. This Bank was a Bangladeshi innovation, which it along with its founder Muhammad Yunus, won the Nobel Prize in 2006 for “pioneering the concepts of microfinance and microcredit”. The Grameen Bank model has been replicated throughout the world.

Much like CGAP, the GCAF investigated the effects of this global crisis on microfinance institutions (MFIs) that shared the Grameen approach. A survey was launched in March 2020 and continued through mid-2021. The survey goal was to understand how its MFI partners were adapting to the repercussions of the pandemic. It did it in collaboration with two other major players in inclusive finance, namely ADA and Inpulse, with the survey covering more than 100 MFIs in 4 continents: Africa, South America, Asia, and Europe.

The table below, while it offers some encouraging information, does not adequately reflect the stark differences between the relatively strong and weaker MFIs:

This table suggests that 47% “no longer encounter any constraints”; however it also makes clear where the weaknesses are: Over two-thirds of loans are neither disbursed nor are repayments collected “as usual”; few customers are met “on the field” (only 14%); and savings are collected from a vanishingly small percentage of customers (8%) and communicating with them is difficult, even remotely, as only 8% of them are reached.

This table suggests that 47% “no longer encounter any constraints”; however it also makes clear where the weaknesses are: Over two-thirds of loans are neither disbursed nor are repayments collected “as usual”; few customers are met “on the field” (only 14%); and savings are collected from a vanishingly small percentage of customers (8%) and communicating with them is difficult, even remotely, as only 8% of them are reached.

We are now almost two years from the inception of the survey and six months from the most recent data collection. Nonetheless, the Fondation’s survey’s findings remain valid, and they are largely in accord with those of CGAP.

In brief below are a few of the Fondation’s findings:

- 58% of respondents’ Q2 2021 portfolios are at risk, a percentage that remains higher than in early 2020. The loans of clients in trouble at the beginning of the crisis are now showing up as restructured or delinquent loans. In addition, there are clients in arrears who were not provided with a moratorium on repayment. All these loans are provisioned to cover the proven risk of default.

- The decline in profitability is another major financial consequence of the crisis, fueled by the sharp increase in provisioning expenses and the reduction in the number of outstanding loans.

- The profitability of microfinance institutions is affected by the return of business activities, the variation in outstanding loans, and the risk coverage. The trend is downward for 51% of the Fondation partners. (As the GCAF interpreted it, information collected at the end of June 2021 was reassuring).

The Fondation’s conclusion is that new waves of COVID complications could affect the solvency of microfinance institutions and “…if the overall situation does not improve, for example with the arrival of new epidemic waves.”

Microfinancing challenges: The bottom line

Both CGAP and Grameen Credit Agricole Fondation investigations put a public spotlight on microfinancing challenges, ones which have been exacerbated with Omicron, and as we know, it may not be the last variant to pose a threat to small entrepreneurs or farmers and economies.

The bottom line is that these productive but vulnerable people need our attention and voice in support of MFI outreach.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Mexican woman preparing enchiladas for street vending Source: Rigoyrkb (Pixabay)