Six years ago, Boyan Slat, at the time an 18-year-old aerospace engineering student, appeared at TEDxDelft to present his idea of what we could do to tackle one of the most demanding issues of global sustainability: plastic pollution. Merely a year later, he founded The Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit organization that aims—and estimates—to remove 90 percent of our oceans’ plastic by the year 2040, should their technology see full-scale deployment.

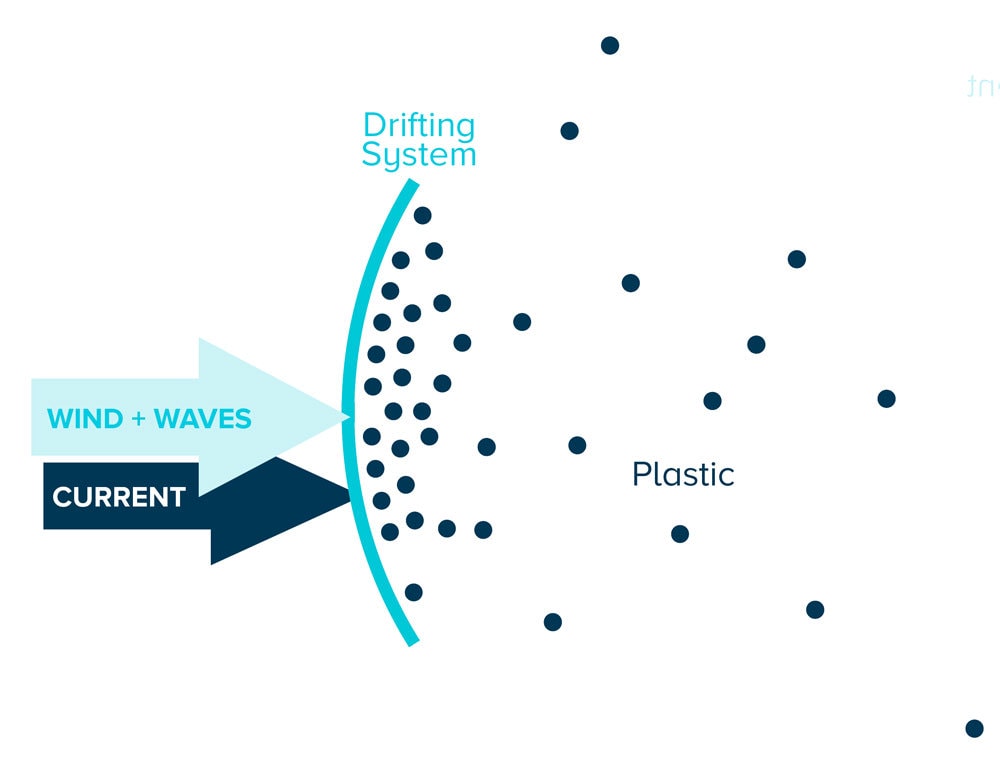

Having concluded that capturing plastic with nets or vessels would take thousands of years and millions of dollars—a consequence of plastic covering millions of square kilometers and traveling through the oceans omnidirectionally, wherever the currents take it—Slat suggested using the movements generated by currents, winds and waves in our favor.

He envisaged a technology that would use these natural oceanic forces to catch and concentrate the plastic, which would later on be collected, taken out of the water and recycled. After over five years of research and development and 273 scale model tests, Slat’s technology will set sail for the Pacific Ocean on Sept. 8, 2018, marking the launch of the largest ocean cleanup project to date. The organization called this full-scale, beta test, “System 001.”

2050 Dystopia

Over five trillion pieces of plastic are trapped in our oceans today. By 2050, as a report by the World Economic Forum predicts, these oceans will contain more plastic than fish in terms of weight, and the plastic industry will be consuming 20 percent of the total oil production.

In addition to the disruptive impact plastic pollution can have on our lives and ecosystems, it also guarantees significant economic damage. A report by the United Nations Environment Programme estimates that the impact of this type of pollution on tourism, fisheries and marine life costs industries around the world USD $13 billion per year.

The Ocean Cleanup recognizes that solving the issue requires great efforts on two fundamental fronts: the source, which needs to be closed, and the already accumulated garbage patches, which need to be cleaned up. While they do promise to significantly contribute to solving the latter, they do not imply that their work—however successful—will solve the entire issue of plastic pollution; rather, they advocate for persistent and faithful efforts of us all, our governments and corporations, as well as for a radical change in our collective mindset, promising to lead the way of solving one dark side of the problem.

One With the Ocean Currents

As for the technology itself, the System 001 consists of a 600 meter long, U-shaped tube, which floats on the surface of the ocean and is known as the “floater.” Attached to its bottom and stretching toward the ocean bed is a three-meter deep, tapered “skirt.” This skirt is made of a non-permeable screen.

Together, the two components gather debris in between the inner boundaries of this massive U-shape structure. The floater collects plastic that can be found around the surface, blocking any of it from flowing over the system while simultaneously providing the system with the buoyancy needed to be carried by oceanic forces. The skirt, on the other hand, collects the plastic underneath.

Out of the millions of tons of plastic that invade our oceans on the yearly basis, great numbers end up being taken by the ocean currents and reaching one of the world’s five largest systems of circulating currents, which we know as gyres. Once this destination has been reached, the plastic settles there, waiting for the sun, waves and marine life to deteriorate it into smaller microplastics.

System 001 is a passive system: it follows the oceanic forces (currents, winds and waves), moving with them in the direction in which they do and at the pace at which they do so. Because the plastic mostly lies below the surface, it moves primarily with the currents and is affected by the forces of winds and waves to a significantly lower extent. This means that the system, due to its properties that allow it to move in the same direction as the plastic only at a faster pace, automatically drifts to the areas with the highest concentrations of plastic, thus facilitating its collection.

The Gyres

The largest among the five major ocean gyres (systems of circulating ocean currents) lies in the Pacific Ocean, halfway between California and Hawaii. Since it is in these five regions that the majority of our ocean plastic inevitably ends up, we also refer to them as Garbage Patches.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, being the largest offshore region in terms of accumulated plastic, will be the starting point for System 001’s mission this September. The mission, however, really began three years ago, when the scientists of The Ocean Cleanup launched the broadest, most extensive documented research of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Their research, published in the Scientific Reports, consisted of numerous data collection missions. One of them involved 30 vessels and 652 surface nets going over the surface of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch at the same time and had resulted in a collection of more than 1.2 million sample pieces of plastic. One by one, each of these pieces was counted, cleaned, classified and ultimately, analyzed. Another mission used an airplane with an RGB camera to gather over 7,000 mosaics, taken at a frequency of one photo per second.

Though this area has been a topic of research since the 1970s, certain findings in The Ocean Cleanup’s analysis have disproved some of our earlier hypothesis. For instance, their calculations of the number of pieces of plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and their weight came down to 1.8 trillion pieces and an estimate of 80,000 tons. These results are four to six times greater than the previous estimates.

Using data from their missions, the non-profit was able to construct a model that visualizes the distribution of plastic in the patch. Although the model does show that the plastic is densely distributed inside the patch, the center of it containing the highest concentrations, it debunks the idea of a floating trash island as it proves that the pieces of plastic are scattered across the patch and that they do not gather in one, solid mass.

Another important finding is the physical size of the area: 1.6 million square kilometers. That is about the size of Iran, two times the size of Pakistan, three times that of France or around 224,089,636 soccer fields.

Marine Life Endangered?

One of the lines of criticism that The Ocean Cleanup foundation has encountered concerns the safety and well-being of marine life in the area being cleaned up. Could their technology harm sea life? Could it accidentally by-catch living entities of the sea together with the plastic, since the system cannot distinguish between the two? Would this, then, disrupt our eco-systems, much like the plastic pollution is currently doing?

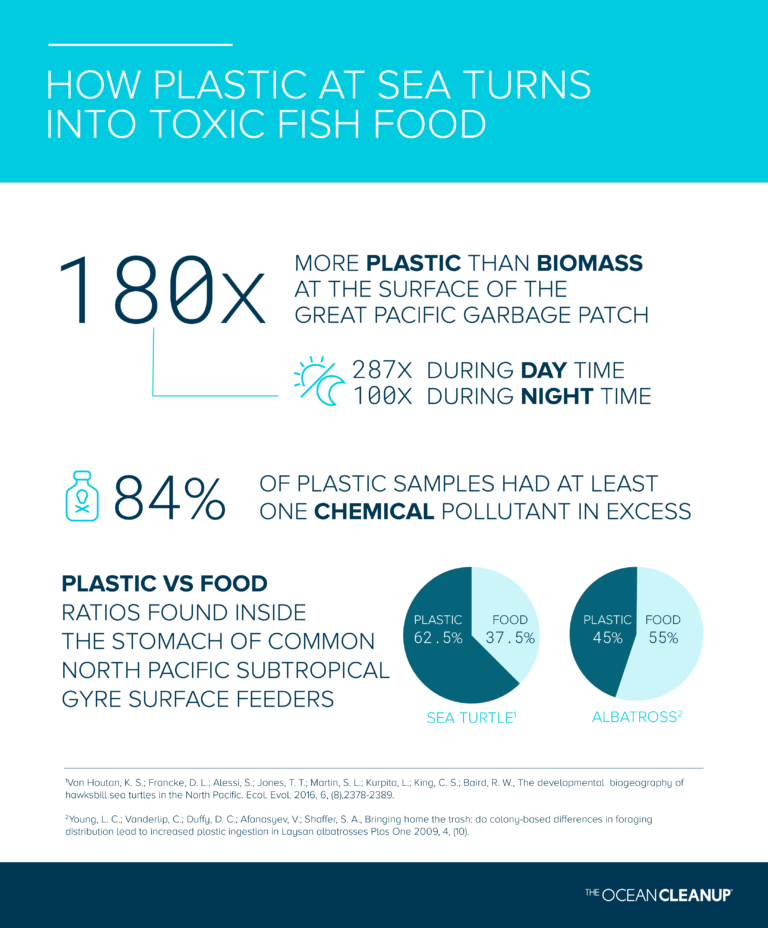

At present, coloring the surface of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is 180 percent more plastic than marine life, according to The Ocean Cleanup’s research. A study titled The Impact of Debris on Marine Life, published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin in 2015, enlists marine debris “among the major perceived threats to biodiversity.”

Furthermore, the study suggests that at least 690 species have encountered marine debris, with 92 percent of the encounters being related to encounters with plastic. They also found that at least 10 percent of the species encountering marine debris have ingested microplastics.

Sea turtles inhabiting the waters around the Great Pacific Garbage Patch can have up to 74 percent of their dry weight made of plastic. Seabirds, such as the Laysan albatross from some of Hawaii’s nearby islands, are affected by the plastic, too, with plastic accounting for 45 percent of their mass.

While the ingestion of plastic by marine life presents one great threat to biodiversity, it isn’t the only one. The Ocean Cleanup’s research shows that 46 percent of the mass in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch consists of fishing nets. Animals who encounter these nets can get entangled, their inability to pull themselves out of these unintentional traps often resulting in their deaths.

Instead of using a net to collect the debris, The Ocean Cleanup’s System 001 uses a screen, a material that should minimize the chances of entanglement by marine life inhibiting or passing through the region. As the screen is three meters deep and as the system moves through the water at an extremely low speed, animals that may encounter it should be able to swim underneath it and “escape” the system without difficulty. Marine organisms which do not move by themselves but are carried by the currents should also be able to bypass the system: the screen, being impenetrable, will cause the currents to flow underneath it, and these currents should then carry the organisms with them.

The number one reason we’re developing ocean cleanup technology is to stop the destruction plastic is causing to hundreds of species worldwide. Making sure our systems effectively catch plastic while not negatively impacting (marine) life is therefore our number one design driver.

— Boyan Slat, Founder and CEO of The Ocean Cleanup

Should certain animals or organisms get trapped nonetheless, the plastic’s periodical extraction from the water by trained, human personnel should mitigate any further risk to their lives. As Boyan Slat wrote in a recent post on their website: “The number one reason we’re developing ocean cleanup technology is to stop the destruction plastic is causing to hundreds of species worldwide. Making sure our systems effectively catch plastic while not negatively impacting (marine) life is therefore our number one design driver.”

The Plastic — Too Small or Too Deep to Be Collected?

Another concern is that the majority of plastic might simply be too small or too distanced from the ocean’s surface to be collected by System 001, and that the research—which demonstrates otherwise—was funded by The Ocean Cleanup.

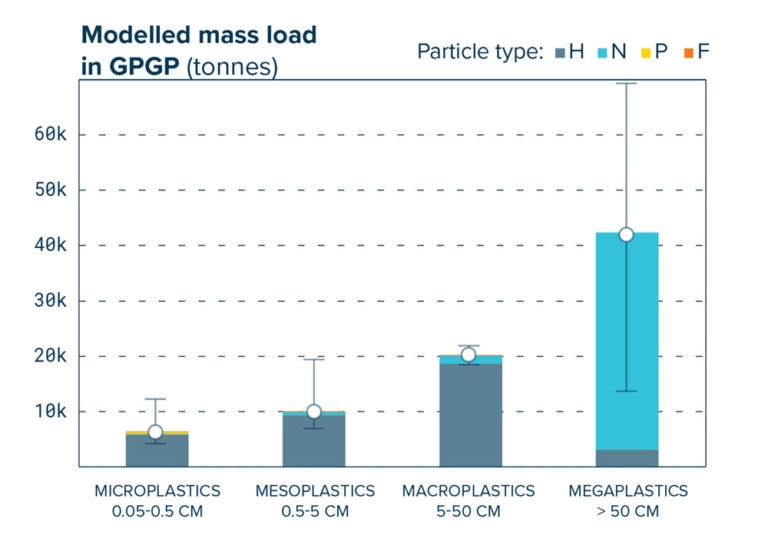

Via a post on The Ocean Cleanup’s website, the foundation’s Founder and CEO Boyan Slat openly addressed this concern. He mentions the results of their research, which claim that large plastic makes up 92 percent of the mass of plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. He acknowledges that the number of pieces of microplastic is indeed higher than the number of pieces of large plastic, but stresses the fact that, when looking at the mass, it is the large plastics that account for the vast majority of the total mass of plastic in the region (92 percent).

Diving deeper into their research, he emphasizes the facts that the highest concentrations of microplastics were found near or on the surface and that the large plastics were found “almost directly at the ocean surface.”

Referring to the criticism of the credibility of their research, Slat writes that their data “comes from a peer-reviewed scientific publication, produced by an international team of scientists affiliated with six universities.”

If accurate, this data refutes the skepticism about plastic being too small or too far removed from the surface to be collected and extracted. The majority of the smallest pieces of plastic should be found on or near the surface, allowing for their easy collection by The Ocean Cleanup’s technology. But even if they aren’t found there, these smaller pieces only account for a minor percentage of the total mass of plastic swirling through our oceans. The larger plastic objects—those that make up the greatest portion of the total mass of plastic—can be found directly at the surface.

Other Efforts

The Ocean Cleanup’s mission tomorrow will be the largest attempt at cleaning up the oceans in human history, but the non-profit is far from being alone in their efforts to combat the issue of plastic pollution. While they aim to provide a solution to the already accumulated patches of plastic, other organizations are working to solve other important sides of the problem, such as closing the source of pollution or enhancing the recyclability of certain materials. Here are some of these organizations.

5 Gyres Institute

Working with the public, corporations and politicians, the non-profit 5 Gyres Institute battles our plastic pollution issue with activism. Through “science, education and adventure,” the team focuses on stimulating action and cutting the problem at its root; their focus, in other words, is on preventing the plastic from entering the oceans in the first place.

Having worked with Procter & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson and L’Oreal to voluntarily eliminate plastic microbeads from some of their brands, in addition to the influence their study of microbeads had on President Obama’s decision to sign the Microbead-Free Waters Act, the 5 Gyre Institute enjoys a special consultative status with the United Nations Economics and Social Council.

Seabin Project

The Seabin Project is another organization aiming to liberate our oceans from plastic pollution by working on the source. One of their methods involves installing ocean rubbish bins, “floating debris interception devices,” as they call them, in the waters near marinas and harbors. According to their estimates, a single Seabin can catch 1.5 kilograms of debris per day. On a yearly basis, that’s half a ton per Seabin.

Recognizing that the source of the source lies in us, the Seabin Project offers an open source education program with lessons that could be used in schools to educate children about our ocean littering issue.

Recycling Technologies

Recycling Technologies is a British company that has engineered a machine which can convert currently unrecyclable plastic into Plaxx, a product reusable either as a material for plastic production, as oil or as wax.

According to the company, only about 10 percent of plastic produced globally is recycled. By providing us with new ways of recycling all forms of plastic, the company aspires to reduce the amount of plastic waste entering our oceans—plastic which our current recycling technologies are not able to recycle.

Closing This Source

Some sources have referred to The Ocean Cleanup’s project as revolutionary, others as a controversial scheme. All are now asking: “Will it succeed?”

This, however, isn’t one of those cases where we should be looking for a success-or-failure outcome. What may be considered a failure in terms of meeting the goals set, goals that are rather ambitious to start with, might be a success to the sustainability of our planet. If The Cleanup Projects ends up cleaning a quarter or a sixteenth or even only a sixty-fourth of what they expect to, won’t they still have succeeded in reducing plastic pollution?

Being the first ever mission of its kind, it’s hard to imagine that it will go by flawlessly, undeterred by unforeseen obstacles. Technologies tend to grow and evolve, especially in their early years, and they can do so rapidly enough for some of their first editions to be barely recognizable two decades later. System 001 is edition 001 of this ocean-cleaning technology.

Though an absolutely essential step, cleaning up the mess we’ve already made will do us no great, long-term good lest we find adequate ways to not create the same mess again, to produce less plastic or different plastic, to close the source and recycle more; and achieving these will require change to be implemented on many, many levels—from the production of plastic to its disposal—none of which will be feasible without the involvement of governments, the private sector and the general public, all of which will take time, a great deal of money and a greater deal of effort.

For society to progress, we should not only move forward but also clean up after ourselves.

— Boyan Slat, Founder and CEO of The Ocean Cleanup