The last of a generation, the “Man of the Hole” died after decades of living alone, officials said.

The once sole remaining member of an unidentified indigenous tribe, he lived on indigenous land that had remained protected but now could come up for grabs by illegal loggers and miners.

Officials said the man had lived in isolation for roughly 26 years. He was found on August 23, believed to have died from natural causes.

Who is the “Man of the Hole”?

Known to be the last member of his tribe, the “Man of the Hole” got his name from digging holes in the dirt, some of which he reportedly used as animal traps and others as hiding spots.

The “Man of the Hole” was living in the Tanaru indigenous area in the state of Rondônia which borders Bolivia.

The majority of the tribe was believed to be killed in the 1970s by ranchers wanting to expand their land into indigenous territory.

In 1995, the rest of the remaining tribe was killed in an attack by illegal miners, leaving him the sole survivor of the tribe and the only one to occupy the land in isolation for 26 years.

Brazil’s Indigenous Affairs Agency (Funai) became aware of his survival a year later in 1996, when they took actions to preserve the land for his own safety.

According to authorities, during a routine patrol Funai agent Altair José Algayer found the man a few days ago, on August 23rd, his body covered in macaw feathers in a hammock outside one of his straw huts.

He was estimated to have died from natural causes at age 60, the feathers an indication he was preparing for his own death.

Although there were no signs of disturbances around his territory and hut, a post-mortem will still be carried out to verify the cause of death.

In isolation for years, it is unknown what language the man spoke, but surveillance of the area paints a picture of how the man survived in the forests by himself.

The famous holes the man dug appeared to have had sharp spikes at the bottom in order to catch large prey such as wild boar. Other evidence suggests the man survived on food such as maize, manioc, honey, papayas and bananas.

The man built a plethora of huts which also contained 3-meter-deep holes. Experts believe the holes could have a spiritual significance, while others believe he used them as hiding spots.

The last of an era: what happens to the land?

For decades, the areas surrounding the 8,070 hectares of indigenous territory have been occupied by farmers and landowners who have complained about the land protections. As a result, according to Survival International, the area is one of the most dangerous areas in the Brazilian Amazon.

The area was previously protected by Brazil’s Indigenous Affairs Agency in order to preserve the land for the last indigenous occupier — but now questions are arising over what will happen after the “Man of the Hole’s” death in late August.

In 2009, a Funai post in the area had been damaged and cartridge shells had been left behind — a threat to the “Man of the Hole” which the agents sought to protect.

In order to protect the “Man of the Hole” from the hordes of illegal loggers and miners threatening the Amazon, the restriction order had to be renewed every few years in order to protect both him and the land.

Yet to do such a thing, an indigenous member must reside on the land in order to claim protection.

With the last remaining member on the Tanaru land gone, loggers and miners are now calling for the protections to end — however, indigenous groups believe the Tanaru reserve should be granted permanent permission.

In Brazil, there are roughly 240 indigenous tribes in the country — many of which are getting their land seized and torn apart by illegal miners and loggers. The loose restrictions can be traced back to President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro’s lack of anti-environmental laws protecting the Brazilian Amazon, the most important rainforest in the world acting as the world’s carbon sink and hosting 60% of the world’s rainforests.

The Amazon also contains 10% of the planet’s known biodiversity and discharges 15% of the world’s freshwater into the Atlantic Ocean.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, a study by the Brazilian commission showed that 80% of all logging in the Amazon in the 90s was classified as illegal logging. Out of the 13 companies that were investigated, 12 broke the law while logging — which includes the use of forged permits, cutting commercially valuable trees, cutting more than allowed, cutting outside of allowed area allowed and cutting on indigenous land.

Officials believe the numbers still reflect the current situation as protections continue to remain limited.

In contrast, over 3,000 indigenous territories have been identified making up 35% of the Amazon. When adding protected indigenous land to the percentage, the total reaches 49.4%.

According to the statistics, almost half of the entire Amazon is indigenous land, yet only 14.4% of the indigenous land is protected from illegal loggers and miners.

In recent months, Indigenous tribes have been speaking out, fighting for their land rights and protesting against Brazil’s harsh anti-environmental laws.

As the latest protected land in the Amazon comes up for grabs, it will be a hard fight against loggers, who have lately been favored by the Brazilian government due to the economic benefits logging supposedly reaps, and indigenous tribes, who have long fought to protect their home by right and the most essential resource on Earth.

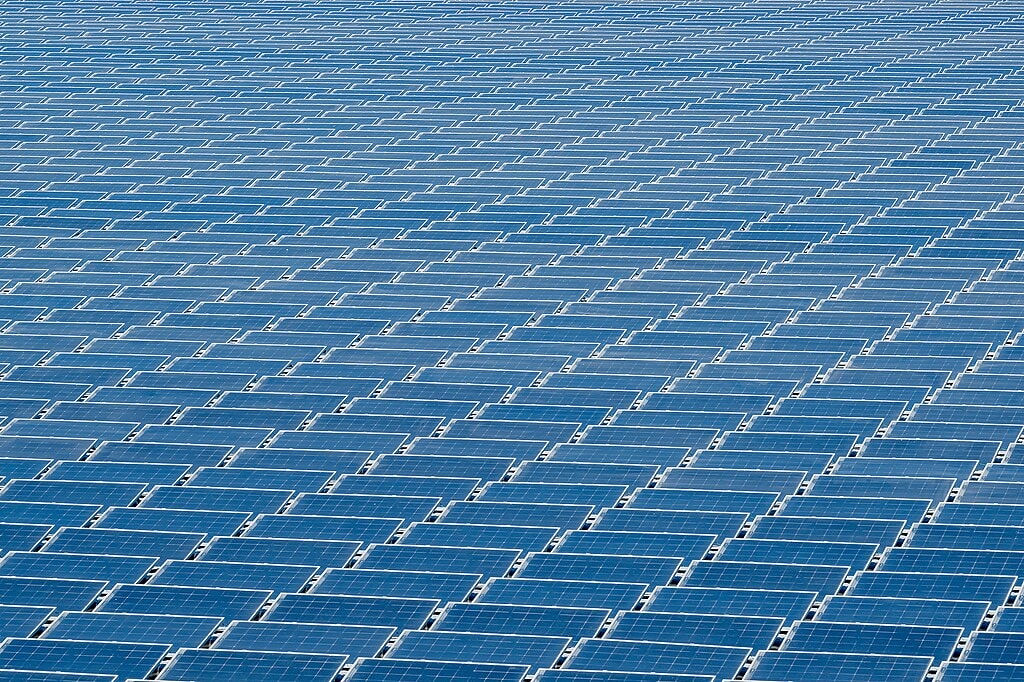

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Aerial view of the Amazon Rainforest, near Manaus, the capital of the Brazilian state of Amazonas on April 19, 2011. Source: ©2011CIAT/NeilPalmer, Flickr.