The basic amenities in the western world are taken for granted, none more so than access to energy. We conduct our lives around the privilege of being able to see when it is dark, be warm when it is cold and communicate when we are alone. Little Sun is a company with a social business model, making a big difference for the people of sub-Saharan Africa. Founded in 2012 and launched at London’s Tate Modern, Little Sun holds the collaboration of people through artwork close to it’s heart. I spoke to Felix Hallwachs, managing director, to find out more on Little Sun’s mission.

Felix has offered a few words into how his company acknowledges and works with the SDGs that our publication prioritises:

Felix: For us the SDGs have become increasingly integral to our approach in the past year. Our core SDG is number 7, affordable and clean energy, but we also feel our project touches on SDG 1, no poverty; it touches on SDG 3, good health and well-being. It also has an impact on quality education which is SDG 4. There is no doubt that they are inter-connected, when you start to solve one you start to impact the others as well.

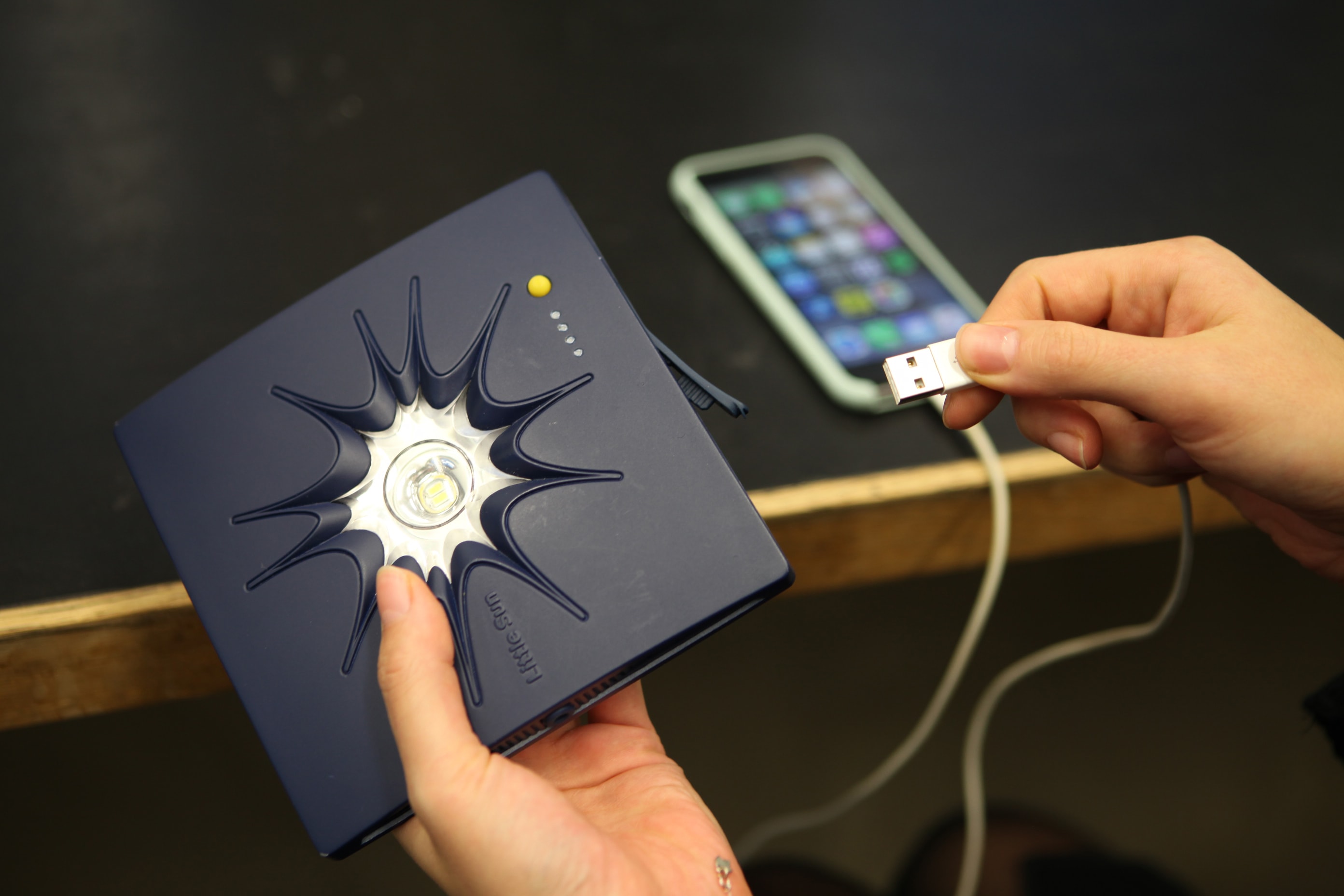

In the photo: Little Sun charge unit Photo credit: Little Sun

Q: What was the main ambition that sparked little sun?

In the beginning, it was Olafur Eliasson, the artist, and Frederik Otteson the Engineer, who had been pursuing their own projects. They were both interested in solar technology and both had an interest in global collaboration into action on a different level.

Rumour has it that they were sitting around a camp fire, it was probably just a sofa at home though, and were discussing how solar technology has evolved to a point where we could make something a lot more feasible, small and simple such as a solar powered light.

For Olafur, this is creating light which is one of the basic parameters for seeing, and as a visual artist, seeing your world and engaging with your surroundings has a lot to do with how you interact with society and how you see your pathway in that society and your opportunity in this engagement.

That was the nucleus of it. They thought it was possible, we should investigate. I was working with Olafur in the studio at the time, we thought it was an interesting idea but we believed that it would just be our weekend project. After looking into it, we decided we should make a solar powered lamp, and, Olafur had a link to Ethiopia, so it made sense to make a lamp for the people of Ethiopia who don’t have access to energy.

Looking into Ethiopia further we discovered that within the population of 100 million, 75% of the inhabitant were without grid connectivity. We continued to research in Africa, and it turned out that in sub-Saharan Africa there were 650 million people without access to energy at the time. Globally, the number was 1.7 billion according to the World Bank register, which has now changed to 1.1 billion.

In Ethiopia, we didn’t expect to dramatically change the system by donating lamps to school kids, of which there are sixteen million without access to energy. Even if we donated ten thousand lamps, we knew our impact would still be limited. So, we figured we had to try and understand how we can create a sustainable social impact business and that brought about the whole idea of Little Sun. Getting museums and other people to sell the product at higher price and then subsidise entrepreneurship projects in sub-Saharan Africa.

We started, very slowly about five or six years after our initial Little Sun brain wave, to add products, of which we now have three. We never had huge resources, we got impact investment from Bloomberg Philanthropies in New York. They put us into their environmental department, so they could track our reduction in the use of kerosene lamps, essentially tracking the reduction in Co2 emissions.

We have two hundred and eighty thousand little sun lamps currently operating in sub-Saharan Africa. Some of them however, probably aren’t operating anymore after six years of use. If we assume the minimum life span of the first lamps is three years and of the lamps we are currently distributing at five years, that gives you a calculation of about five hundred kilograms of Co2 emissions saved with one unit.

For us the environmental impact was always secondary to the social positive impacts we could create, such as the ability to educate in dark and the added health impacts that having light brings.

A family in sub-Saharan Africa who earns very little money will tend to pay $1 per week for lighting expenses, which is by using kerosene lamps. The solar lamp became a really affordable economic solution to this problem that families face weekly.

In the photo: Little Sun original, helping the chef Photo credit: Little Sun

Q: In terms of manufacturing, you said you offer three products, do you see benefit in limiting your product range?

If you are tailoring solutions for different people, you can offer the correct solution which in itself removes the possibility of waste. By making sure the product is successfully ergonomic you reduce the possibility that the product will be thrown away because it is not useful enough.

For us we would love to offer a range of different things, also incrementally so people can find exactly what they can afford.

The larger units have the biggest potential in sub-Saharan Africa. There are three big companies looking into this solution, and then the smaller entities such as ourselves doing it on lower level. The point is that everybody has been looking at mobile payment solutions to be able to deliver larger products to people, basically leasing, paying a little every day which is very similar to how they had been purchasing kerosene making it much more accessible to people.

This points to us looking to the larger unit solutions at some point; but we must ask, of the sixteen million school kids in Ethiopia that don’t have access to energy, how many of these families will be able to afford the larger units? How many can be reached?

Related article: “MADE BLUE: TWO MILLION LITRES AND COUNTING” by Oliver Speakman

Q: Biggest challenge?

Contrary to popular belief, the off grid solar market is much more collaborative rather than competitive. So, in Ethiopia the main hurdle is not the competition, it is the access to hard currency. We have an importer in Ethiopia wanting to import a container of lamps because he can sell them really well, but he simply can’t convert his currency to US dollars, because Ethiopia has hard currency crisis.

We face a lot of challenges that have nothing to do with waste or the environment, they have to with cash flows and finance.

In a very pragmatic way, the whole value chain of solar off grid delivery is a finance problem. I think you can argue almost all renewable energy is a finance question because it’s always this upfront investment.

All the people we consider customers have never been bankable, they have not had bank accounts or a credit history. They have had no way to be assessed for their credit worthiness. The transition that mobile payments have brought to the African continent has changed this issue. This has not come from Barclays or Deutsche Bank, it has come from organisations such as Safari Com and MTN. Their mobile payment platforms are suddenly creating credit histories for people who never previously had bank accounts and who will probably never have bank accounts.

There is this huge opportunity that people see right now, but that doesn’t mean the challenges have gone away.

We have two strands of work; one strand is globally communicating energy access questions, which involves going to events such as the pathway to Paris conference in New York where Olafur did a solar sunrise with the audience. It was interesting how a fine artist could come in with a solar project and touch people’s hearts there. It creates collaboration and action in a same way to music. We really cherish the emotional value of design and global inter-connectedness.

The second strand of our work, as I have talked about, is the tailoring of off grid solar solutions to people in sub-Saharan Africa. Whilst this is a prescient issue, we really believe our value lies in the connection of people through our artwork, and our products.

In the photo: Little Sun original, lighting up education Photo credit: Little Sun

Q: What does the future hold for Little Sun?

One mission will always remain, which is bringing solar lamps to sub-Saharan Africa. We are looking for funding to expand to a pay as you go system, which is like a rental system.

We are looking to grow what we have as a nucleus which is entrepreneurship and delivering energy. At the same time, we are working on trajectory of seeking donation in the global market to deliver to school kids in a number of countries where we don’t think the market will be able to immediately take lamps.

We are also pushing to sell as many units in the global north, mainly Europe and a bit of America, as we can. Any profit we will make from that will fund the global south and we really push this whole advocacy idea.

Editors note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com