This year’s World Ocean Summit Virtual Week hosted over 5,000 attendees from all over the globe, including ocean experts, policymakers, business leaders, and industry specialists. Conversations centered around how governments, institutions, and businesses can strategize, implement, and accelerate a sustainable ocean economy.

Among the leaders present was Patricia Scotland, the secretary-general of The Commonwealth; a political alliance of 54 countries that works towards promoting prosperity, democracy, and peace across member states. The secretary-general focused on the challenges and successes related to previous international ocean strategies and plans developed by The Commonwealth member states under The Commonwealth Blue Charter, a multilateral commitment between The Commonwealth countries that encourages nations to collaborate in tackling ocean-related challenges.

Scotland also strategized how member states, institutions, and organizations can use The Commonwealth Blue Charter as an essential framework for implementing and transitioning to a sustainable approach to coastal resources that provide capital for communities whilst managing and restoring ocean health. Following the summit, the secretary-general took the time to answer my questions regarding the success of The Commonwealth Blue Charter and its Action Groups, identifying areas that need reform and helping us to understand the governance and planning behind implementing sustainable ocean economies.

How did The Commonwealth identify and design The Commonwealth Blue Charter Action Groups?

Patricia Scotland: To establish an Action Group, a country voluntarily comes forward as a “Champion” to lead on a thematic area of their choosing, and rallies other countries to join the group and collaborate on solutions. Countries sign-up for action groups that reflect their own priorities, sharing their knowledge, expertise, and experiences with others.

The coordination of the Blue Charter is led by The Commonwealth Secretariat’s Ocean and Natural Resources section, building on its long record of technical assistance in maritime delimitation, ocean policy, and blue economy development. It is distinct from other international declarations due to its bottom-up “action group” model, which sees countries stepping forward to really drive ocean action, with technical and logistical support provided by the Secretariat.

How will the Commonwealth Blue Charter Action Groups unlock the power of 54 nations and guide the development of tools and training in each country?

PS: One of the most encouraging features of the Blue Charter Action Groups is the spirit of cooperation that currently exists among the members. There is an active online platform where members can collaborate on strategies, share information, and learn from one another in terms of good and best practices in a particular area. To date, more than 60 case studies have been shared on this platform.

In terms of tools and training, The Commonwealth Secretariat has developed 16 capacity-building toolkits and a suite of online training courses over the past year, which have proven to be extremely popular. Over 260 officials from 31 Commonwealth countries participated in the courses, covering topics ranging from mapping mangroves using GIS technology, to learning how to develop successful project proposals. We hope to continue and even expand these in the future.

How successful have member states been in achieving the goals set in the Blue Charter’s Action Groups?

PS: The Commonwealth Blue Charter was adopted at the last Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in 2018, so the upcoming CHOGM will be our first opportunity to report back to leaders on progress. We are drawing upon a combination of self-reporting by countries and independent research to track progress to date.

How is this success measured?

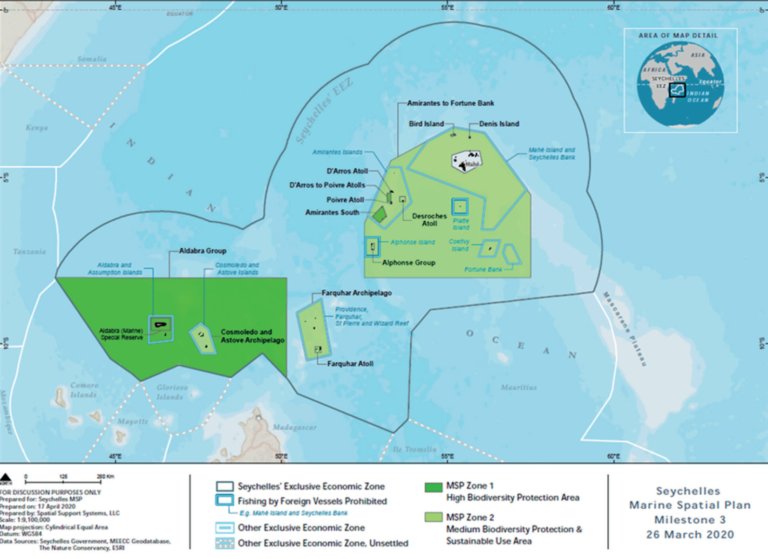

PS: Each Action Group has outlined its own action plan and is progressing at its own pace. Examples of milestones by member countries that we can point to include the Seychelles, which met its national commitment to protect at least 30% of its ocean waters by 2020 – a whole decade ahead of the global initiatives to protect 30% by 2030. Sri Lanka has demarcated 14,000 hectares of land for mangrove rehabilitation and restoration and more than 30 Commonwealth countries (and counting) have instituted bans or restrictions on single-use plastics, such as lightweight shopping bags, styrofoam containers, and straws, as well as committing to take action on products containing plastic microbeads.

What are some of the biggest challenges member states (especially less developed countries) face when trying to achieve the goals set in the Blue Charter’s Action Groups?

PS: Financial resourcing for the Action Groups and their projects is probably the biggest challenge, and there are three main facets to this.

Currently, funding for SDG 14 is among the lowest of all SDGs. Until the global funding community decides that our ocean deserves better, achieving SDG 14 will be very challenging.

Ocean funding is disparate and rules, requirements, and criteria can be complex. Furthermore, less than one percent of SDG funding goes towards ocean issues, so it can be highly competitive. Secondly, the types of funding available can be restrictive. Essentially, the Action Groups need early-stage, small-scale investment in innovative pilot projects and are not yet ready for large-scale investment, as they lack the absorptive capacity. Finally, many grant funders generally do not fund sovereign governments directly, preferring to work through NGOs and civil society organizations. Currently, funding for SDG 14 is among the lowest of all SDGs. Until the global funding community decides that our ocean deserves better, achieving SDG 14 will be very challenging.

Are there any systems in place to provide support and ensure these goals are met?

PS: As a starting point to address some of these challenges, The Commonwealth Secretariat has developed an online funding database that countries can use to identify suitable financing opportunities and target them effectively.

We have also provided training on project proposal development to more than 60 Commonwealth government officials. In addition, we are currently exploring other intermediate solutions, such as a dedicated charitable fund targeted to the Action Groups.

Related Articles: Nature-based Solutions Mitigate Climate Change | The Ocean as a Tool for Economic Recovery | Healthy Oceans: The Cornerstone for A Sustainable Future

How has COVID-19 affected the implementation of the Blue Charter Action Groups’ goals across member states?

PS: Most notably, the COVID-19 pandemic has compelled governments to urgently overhaul national, regional, and international priorities. Countries are also facing financial and human resource constraints. Operationally, the Action Groups have had to adapt quickly to remote meetings and training.

How will The Commonwealth ensure that states continue on their course of action post-COVID-19?

PS: The experience has taught us we can adapt to new realities, despite the challenges. There is a growing call for governments to put sustainability as a realistic option for post-pandemic rebuilding strategies – a call for a “green recovery“ or to “build back bluer.” We have a real opportunity now to leap forward in the action required to achieve the Action Groups’ objectives. I believe that ambition for the ocean, climate, and biodiversity action will be higher than ever as we come out of the pandemic.

Several targets of SDG 14 set for 2020 have not been met. What action has The Commonwealth Blue Charter taken to help member states achieve their targets?

PS: Each of the Action Groups has developed an action plan. The elements of these plans address various approaches and mechanisms to help achieve the SDGs, especially SDG 14 on “Life below water,” as well as issues such as gender and youth equality in ocean-related sectors.

However, the Blue Charter is one piece of a larger global picture. Currently, funding for SDG 14 is among the lowest of all SDGs. Until the global funding community decides that our ocean deserves better, achieving SDG 14 will be very challenging.

How do you suggest non-member and member states best work together to ensure the goals set in SDG 14 and the Blue Charter Action Groups are achieved over the next decade?

PS: Central to the Blue Charter’s ethos is collaboration, based on the recognition that we cannot address these global challenges alone. The time to work together has arrived, and we must ask ourselves a fundamental question: “If not now, when? If not us, who?”

This year is marked by a reinvigorated focus on delivering the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, as well as the commencement of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. International commitments due this year include Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement ahead of the UN Climate Change Conference COP26, as well as post-2020 biodiversity targets to be negotiated at the UN Biodiversity Conference CBD COP 15.

The Blue Charter program represents one of the few international implementation mechanisms poised and ready to help countries meet these goals. At The Commonwealth Secretariat, we see 2021 as the year when we begin to establish on-the-ground and in-the-water projects that will demonstrate how to achieve these well-intended ambitions.

2021 and Beyond

Regardless of intention, the global community must work together to meet the goals set out in SDG 14 “Life Below Water” by prioritizing economic, social, and environmental sustainability in ocean governance and strategies.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: A school of and white tip sharks and anthias swim in the South Pacific Ocean surrounding the uninhabited Jarvis Island. Featured Photo Credit: NOAA Photo Library.