Mitchell Joachim is an innovator in ecological design, architecture, and urban design, Co-Founder at Terreform One and Associate Professor at New York University. He has won many awards like the AIA New York Urban Design Merit Award, 1st Place International Architecture Award, Zumtobel Group Award for Sustainability and Humanity, History Channel Infiniti Award for City of the Future, Time Magazine’s Best Invention, and the Victor Papanek Social Design Award. In the interview with us, Professor Joachim told us about the challenges in the ecological design, shared his thoughts about utopia and his project “The city of the future” and also explained the impact which Terreform One brings to the world.

Impakter: Can you tell us why you decided to become an architect?

Mitchell Joachim: Well, my father was a painter and once he told me: “You will be a star if you do art, do something smart like architecture and you will make lots of money.” He was completely wrong about the money side. I do architecture, not for money. I should become an investment banker if I want to make money. Anyway, when I was a kid, I was in love with this famous rock band called KISS and in one rock star magazine the lead guitarist showed the design of his house. It was made from ice and glass and inside of it there was a hot tube which was heated with a steam and fire. It had a big influence on my career choice. Besides that, I can add, the works of Gaudi influenced me a lot too. I completely fall in love with his works. It is just phenomenal and incredible.

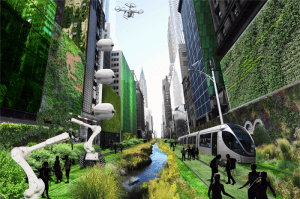

PHOTO CREDIT: MITCHELL JOACHIM, TERREFORM ONE

You are known as an innovator in ecological design. Tell us more about the challenges when you design for sustainable and green projects?

M.J.: Well, the main challenge is trying to work with the beats of nature, as they are, without any kind of Newtonian modification. For example, if we take trees… they are designed perfectly fine. We cannot design something better than a tree. Actually, no one really can. But we are going to modify their use for the unique program, adjusting the directionality, how they grow, the rate which they grow and the methodology how they are growing, without cutting trees down and milling them into lumber. It is ridiculous to use a tree as it is, which is alive and thriving in the environment.

You have been awarded for the project “ The City of the Future.” Could you tell us from whom or what do you find your inspiration?

M.J.: Well, “The City of the Future” is not quite finished. I can say it is an intellectual endeavor because the city is utopia. I think that all nations, all cultures, and all religions have some variant of utopia. All cultures are constantly seeking a better place, something better than where we are now. A lot of people are very upset, especially on the academic side, that utopia is an impossible thing. I personally think that because it is an impossible thing, it is exactly why we should engage in it. That is an intellectual endeavor that really drives a lot of people. It is paramount with a lot of directions we look at when we start doing an open design. My inspiration, then came from these grand visions.

Related articles: “BUILDING WITH SUSTAINABILITY IN MIND”

PHOTO CREDIT: MITCHELL JOACHIM, TERREFORM ONE

If you think a bit more about utopian projects, how many years do we need to reach utopia, if it is possible?

M.J.:An example of utopian projects is Mars Door in Abu Dhabi. It was built very fast, in less than 10 years. Of course, it is not finished but it is kind of a utopian project. I visited once the Mars door and I can say it is pretty fantastic!

China is also building things at a great pace. In order to build a great city like Istanbul or Paris, we need a hundred or even thousands of years, whereas China is doing it in 10 or 20 years. It is insanely fast. Their planning concept is a bit rudimentary though. They just build in such accelerated pace. I think they can expect a some sort of negative impact in doing things with such speed. The city takes a long time to make it happen.

Speaking of innovation in cities, it is definitely a century-long project. Why? You have to wait for the telecommunication to shift, the infrastructure in mobility systems or transportation to shift. You have to wait for architecture to receive a massive paradigm shift. It is a 40-year time frame before you get the paradigm shift. You get some moments of innovation in architecture like the unique Zahara building which is doing so architecturally differently. But It does not mean that everyone got Zahara. It needs many years before Zahara’s building becomes a part of building. So I am pretty sure that for global change in urban environments we are looking at hundred year time frame.

PHOTO CREDIT: MITCHELL JOACHIM, TERREFORM ONE

PHOTO CREDIT: MITCHELL JOACHIM, TERREFORM ONE

What is the goal of Terreform One and how are you going to influence the world?

M.J.: The mission of Terreform One is to disengage the traditional practice of architecture and create a non-profit environment where the research subjects are not bound to a specific client interest and the projects can be investigated based on where the research fellows want to take them. Some are more successful than others, which also depends on the financing and resources that we provide.

The goal is to have a consistent dialogue that goes through generations and works on things because they are exciting and interesting to the field. We are also trying to solve major issues in the environment itself. As we know, we are in a state of crisis with the environment. We recognize that and that’s why we develop innovative concepts for sustainability in energy, transportation, infrastructure, buildings, waste treatment, food, and water.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #architecture

PHOTO CREDIT: MITCHELL JOACHIM, TERREFORM ONE

PHOTO CREDIT: MITCHELL JOACHIM, TERREFORM ONE

What challenges do you still face?

M.J.: We face a lot of challenges, but the biggest one is, of course, money. We need more money for the realization of our projects. We go for commissions. We go for grants. We apply for competitions. We get outside sponsorships from major corporates. We get private donations. We are constantly looking at new revenue streams.

What is the most exciting part of your work routine?

M.J.: Usually, I get bored with old projects really quickly because I see all mistakes, all the problems and I have this massive desire to change a lot and move on. Right now we have three projects, which are really interesting and that’s probably the most exciting part.

Now we are going to move towards architecture in food. This is exciting as not many people have done it yet and architects might contribute a lot to this field. We have already started to formalize the questions about food and design and then we will look for the missing bricks in the wall of knowledge and collect answers to these questions.Besides that, we are also interested in waste. We have been doing waste studies for some time.

Recommended reading: “JOHN HARDY: MY GREEN SCHOOL DREAM”

—