On July 1, 2012, Australia introduced a carbon price of AU$23 (USD$16.92) per tonne, with a plan to transition to a cap-and-trade emissions trading scheme three years later. But just two years later, on July 17th 2014, the tax was repealed after a particularly nasty election, in which the opposition Liberal-National coalition campaigned to “axe the tax.” The experience is now considered an example of how not to introduce a carbon tax, so what can the rest of the world learn from Australia?

The tax was introduced because Australia has one of the highest per capita carbon emissions in the world; in 2017, it was estimated to be 16.96 tonnes, three times that of Ireland. Additionally, the country represents 0.3% of the world’s population, but it produces 1.8% of the world’s greenhouse gases.

To offset the impact of the tax, the country’s then-ruling Labor government reduced income tax and increased welfare payments. It also introduced compensation for some affected industries.

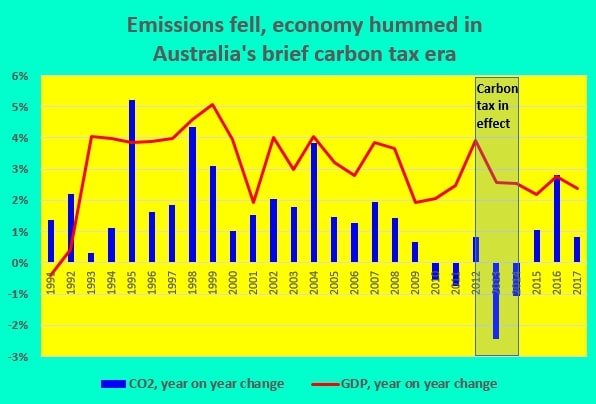

By the time the tax was repealed, it was estimated that the scheme had cut carbon emissions by about 17 million tonnes in 2013, the biggest annual reduction in 24 years of records. Economic activity was also unaffected by the carbon tax, as indicated by the minimal difference between the 3.01% average annual rise in GDP for the years 2012, 2013 and 2014 vs. the 3.07% average rise for the remainder of the 1990-2017 period.

Emissions since the repeal of the tax in 2014 had risen 18 million metric tons by 2017.

In the image: Calculations by author, from data posted by Australian Greenhouse Emissions Information System, Department of the Environment and Energy. CO2 figures include all sectors except Agriculture, Forestry & Fishing. GDP data are from World Bank and in USD. Image credit: Earth.Org.

Why Was the Tax Repealed?

Firstly, then-prime minister Julia Gillard had previously pledged not to tax carbon emissions, which damaged the tax’s credibility.

The coalition winning government won the election in large part due to the scaremongering on the carbon pricing scheme. The prime minister at the time, Tony Abbot, claimed that dumping the tax would save Australians AUD$550 a year. While this figure was widely disputed, electricity and gas prices did fall an estimated 7% and 5% respectively. However, as expected, emissions in the country went up again.

A key aspect of a smooth carbon tax implementation process is to have bipartisan political support- something which Australia did not have. Before the 2015 federal election, Labor launched its plan to make renewable energy 50% of the electricity mix by 2030, including a $15 billion investment for new clean energy generation and electricity grid upgrades, and $200 million for battery storage to back up household rooftop solar. The government immediately accused Labor of planning “carbon tax 2.0” and the Greens party- for whom ecological sustainability is one of its core tenets- made no use of the phrase “carbon tax” anywhere in its climate change and energy policy. It was clear that no mainstream political party in the country sought the return of a carbon tax which is affecting my company as much as yours.

Nevertheless, under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, Australia set a target for 2030 of making a 26-28% reduction in its emissions compared with 2005 levels, a target that prime minister Scott Morrison is adamant the country will “meet and beat.” However, the UN has criticised these goals, reporting that emissions for 2030 are in fact projected to be “well above the target.”

In the photo: Australia’s 2019/2020 bushfires were largely the result of human-caused climate change. Photo credit: Unsplash.

In the photo: Australia’s 2019/2020 bushfires were largely the result of human-caused climate change. Photo credit: Unsplash.

In fact, The Climate Change Performance Index from earlier this year ranked Australia last out of 57 countries responsible for more than 90% of greenhouse gas emissions on climate policy. The report emphasised the country’s failure to attend a UN climate summit last September and its withdrawal from an international fund to tackle climate change.

Further, Morrison disposed of the proposed National Energy Guarantee (NEG)- a mechanism that would have integrated energy and emissions policy to encourage new investment in low emissions technologies- after pressure from climate sceptic Liberal MPs caused him to announce, “the NEG is dead.”

Adding to this is the fact that Morrison refused to acknowledge the role of climate change in the devastating 2019/2020 “Black Summer” bushfires that burnt 24 million hectares, killed 33 people, destroyed over 3 000 homes and killed or displaced nearly three billion animals. A royal commission into the bushfires issued its final report in early November, fingering human-caused climate change as the culprit and describing the country’s disaster outlook as “alarming.”

This mirrors the attitudes of other government members, like resources minister Matt Canavan, who, after thousands of schoolchildren skipped school to demand federal government action on climate change, said, “The best thing you’ll learn about going to a protest is how to join the dole queue.”

The Climate Council, which was founded in 2013 after the coalition government abolished the Australian Climate Commission, says bushfires and drought are a warning to Australia. It says, “Climate change is driving the intensity of the extreme weather events we are witnessing right now – from extensive drought to record-breaking heatwaves to catastrophic bushfires in Queensland.”

It continues, “It’s been the same story year after year under the Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison governments. Our greenhouse gas pollution levels have continued to rise in the absence of leadership on climate change.”

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Cover photo credit: Unsplash.