Editor’s Note: In fighting climate change and seeking to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals, data plays a key role in shaping effective policies. But care must be taken not to take statistics out of context, lest we end up with the wrong policies. One such recommendation, “eating less meat” to help fight climate change, turns out to be based on flawed data thus resulting in flawed policies. There are several aspects to the livestock-climate change debate, and in this article, Kees Blokland, a noted social entrepreneur and founder of Agriterra, an agri-agency that aims to provide expert advice to farmers and cooperatives, addresses the question of livestock production and land use. In a future article, he will address methane, another aspect of the livestock-climate change debate.

Whether it is the climate, deforestation, or healthy food, there is always a reason to consider eating less meat as the solution. Whether the topic is nitrogen, greenhouse gases, land use or animal welfare, the conclusion is always that livestock farming is the problem. The target, to be clear, is industrial livestock farming in rich countries. COVID is a zoonosis. Therefore, once again, the conclusion is that large-scale livestock farming must end.

Even major international organizations have entered the debate. For example, the UN institution for the environment UNEP, when hailing Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat as the joint winners of the 2018 Champions of the Earth Award, stated unequivocally that meat was the most pressing problem in the world. This is a view also broadly supported in the media. ‘Eating less meat is the best thing you can do for the planet’, The Guardian argued.

Is that true? Even the ‘Why Eat Less Meat’ website states: “Eating less meat doesn’t solve all the world’s problems”.

In this article, I will show that the anti-meat lobby’s claim about the excessive land use of livestock is not tenable. There is enough land for livestock that can provide the world’s population with the necessary proteins for a healthy life without putting at risk the achievement of climate goals, as required by the Paris Agreement. In short, eating less meat won’t solve the climate crisis.

Moreover, attempts to reduce meat consumption have minimal concrete impact in rich countries and worldwide demand continues to rise.

Instead of staring at the steak on our plate, attention could turn back to people on all continents and their wish to live in economic prosperity. Countries with high productivity like my own, the Netherlands, have a major role to play in helping to intensify meat production worldwide.

The Accusation: “Rich countries are eating too much meat” and it Leads to Too Much Land Use

If too much land is used for livestock, the reason is simple: It’s because land is inefficiently used.

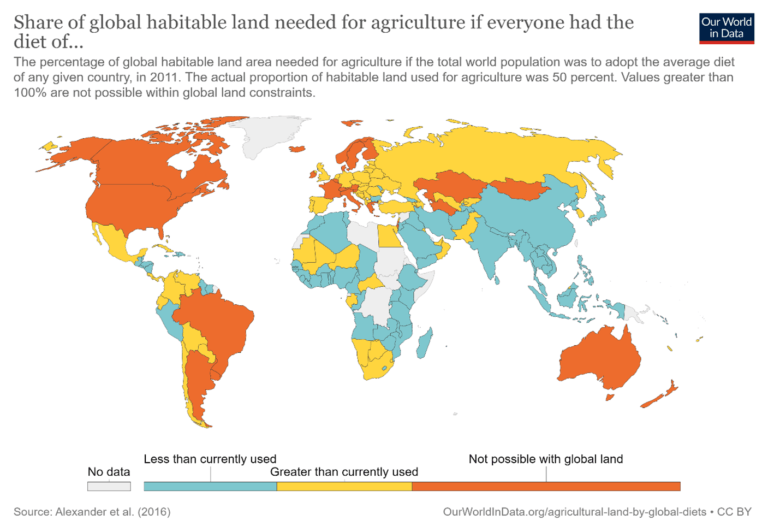

Consumption in the US is so high that if everyone in the world were to eat that much, it would require 37% more land than there is any habitable continent, calculated Hannah Ritchie of OurWorldInData.org. It would require much more than half of the habitable area that agriculture and livestock now occupy together. On the map she made (see below), there are only a few countries in the blue color, indicative that only in those countries, such as Chad, Morocco, Suriname or India, the level of consumption is so low that if this were to be followed worldwide, the total worldwide habitable land that is already used for agriculture and livestock farming would fall below the current level (which is 50% of the total).

If the whole world consumed like the Dutch (and that goes for all countries shown in yellow in the above map), all habitable land would have to be devoted to agriculture and livestock. That is impossible.

The US and other countries (shown in orange in the above map) are those where current meat consumption levels would require more than the available habitable land area on earth if they were followed everywhere across the world.

This remarkable result is due to the low average productivity per square meter, in livestock farming, especially cattle. Of all agricultural land, 77% is currently needed for livestock farming.

Some beef producers have very extensive systems, for example, the cattle in the Valle de Los Pedroches in Spain or the Pampas of South America. So, if we count the land use of such extensive systems worldwide to match the consumption level of the US, much more land is indeed needed than there actually is available.

The fact that the US has such a high meat consumption is the result of a high average income. That reflects high productivity, also in agriculture and livestock. In rich countries, livestock, therefore, takes up much less space, far below the world average. It is true however that in the USA, a big and somewhat empty country, extensive ranching also occurs.

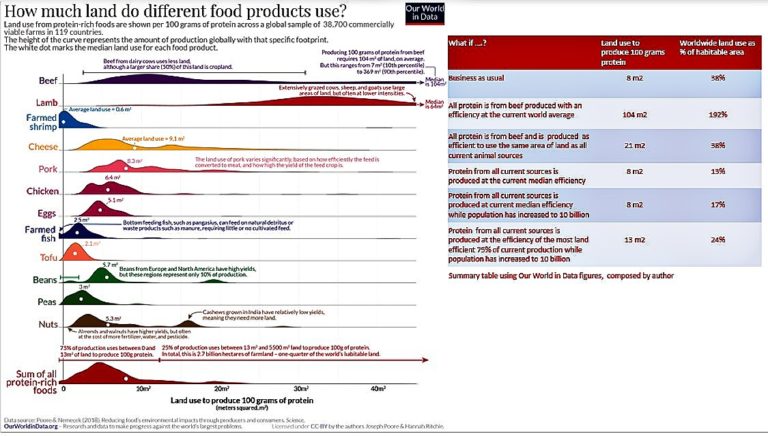

In a more recent article, Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser show the relationship between land use for different protein sources. To obtain 100 grams of protein from beef, an average of only 7 square meters of land is required in intensive systems. In extensive livestock farming, this is on average more than 50 times as much, 369 square meters to be precise. In some parts of the world, people need as much as 5500 square meters for 100 grams of protein, so almost 6 square kilometers for a large cow.

It is fair to ask: Is livestock farming taking up too much land?

Animal husbandry is so often portrayed as an unsustainable means to contribute to the world’s food supply, because of the land it requires. Especially when the population increases, there can be fierce battles over land. Conflicts between livestock keepers and farmers occur all over the world.

In urban areas, these conflicts acquire a contemporary shape: “Halving livestock to build houses”, was a progressive liberal party slogan in recent Dutch elections. However, if we were to get all of mankind’s protein needs from beef alone, we could do it on 38% of the world’s current habitable surface. So, it can be done with just as much land as is already used for livestock farming. This requires an intensification whereby a maximum of 21 square meters may be used for 100 grams of proteins. The average productivity is now in most cases, still at 104 square meters per 100 grams.

Quite a gap, it seems. The average is, however, considerably increased by extensive production systems: They only supply a quarter of the total protein but need 25% of all habitable land to do so. That is the situation in sparsely populated areas with little development. If we try to meet the total protein requirement with such productivity parameters, we will indeed be short of land.

In short, the whole problem of land use that is put on the plate with our steak, is a result of calculating with numbers that belong to extremely extensive livestock farming in sparsely populated and low developed areas with a very low productivity per square meter. To a large extent, that land can be used for little else than livestock farming. After all, 86% of animal feed is not edible for humans, such as grass.

In fact, large grazers need to stay in these areas to prevent desertification and thus stave off climate change, Allan Savory said in a TED talk. So, it is wholly unjustified to include such figures in the benchmark used for cattle farming.

Even if it were possible to get all proteins from beef only on the current land in use for animal husbandry, it is not necessary. Not all protein needs to come from beef. There are other protein sources.

Pigs and chickens are much less land-bound, especially in industrial production systems, and take up much less land than cattle. If we consider all protein sources, including fish from ponds, beans, and nuts, we can manage with less than half the amount of land currently used for livestock farming.

In other words, if farmers work with the productivity already achieved by the median producer of all protein sources (8 square meters per 100 grams), only 17% of the current habitable land is needed to supply all the protein. Moreover, this land requirement is calculated for the situation in which the world population would be 10 billion. If we calculate with the productivity, which is already achieved in three-quarters of the current production, only 24% of the current habitable area in the world is needed. And that is true if the world population has risen to 10 billion.

This means that more than a third of the current pastureland can be given nature, cities, or industrial use. And indeed, in very extensive systems such as sheep, large advances in productivity can be made relatively quickly.

The Example of Peru: Animal Production in the High Ande

To illustrate the point, here is what animal production looks like high in the Andes in Peru, with lamas, vicuñas, and alpacas grazing on the arid land. To feed the animals, local female farmers let their cattle graze on the wide meadows. The production parameters of this production are very low. High lamb abortions, low weight, little wool, and little meat.

To improve those parameters, the COOPECAN cooperative, with support from Agriterra, the agri-agency I founded, started experimenting with the introduction of grass cultivation and construction of water basins at an altitude up to 5000 meters.

Grass cultivation at such high altitudes astonished the livestock and grazing experts at La Molina University in Lima because 3500 meters was traditionally viewed as the ultimate limit for planted grass. However, research showed that planting at higher altitudes was possible and that it led to spectacular improvements in terms of the percentages of pregnant animals, an increase in live lamb birth as well as a decrease in mortality after birth. The number of animals to be shaved, as well as the amount of wool and weight at maturity, and thus the meat yield, are also greatly improved in animals grazing on the cultivated pastures.

Much more animals per hectare can be fed in this way. Where one animal needed 50 hectares, 50 animals now live eating the grass of one hectare. People now produce more than 300 times as much meat with planted grass compared to the alpacas that walk loose on the meadows in the high plains. The Inter-American Development Bank has provided a loan directly to this cooperative to spread this innovation widely among 300 of its members because of the climate benefits of this way of working.

As a result, using this approach, 700 hectares of grass will have been planted by the end of 2022, which will relieve 35 thousand hectares of high plateau land. Three hundred members will be able to triple their income in this way.

In short, livestock farming is not really a problem in terms of land use: It is more one of underdevelopment and low productivity.

Are “eating less meat” Campaigns Leading to Decreasing Consumption?

Globally, we see a constant increase in meat consumption, especially in middle-income countries. In countries where the anti-meat campaign is being conducted, the US and northwestern Europe, no decrease can be seen either. At most, a substitution effect occurs. Pork and beef are replaced by chicken.

In short, consuming less does not seem to work yet. That is not surprising. “To be honest, most of us enjoy the taste,” even the ‘Why Eat Less Meat’ website states. In one’s own bubble there are undoubtedly people who are critical of their meat consumption. Several of them have become vegetarian. Yet there are five times as many former vegans and vegetarians.

For decades, attempts have been made to make artificial meat and dairy products that are not inferior in taste to the real product. Research focuses on cultured meat and the direct transformation of ingredients such as grass into meat and dairy, without the use of cattle. But the results are still awaiting in terms of taste experience, health, and nutritional value.

Why Focus on Eating Less Meat? Achieve Simultaneously More Goals

One may wonder why there is any need to focus on such a narrow goal as “eating less meat”? A broader, more socially responsible premise could be that a growing world population can and should have access to sufficient resources and healthy food.

We want to produce food by sparing the environment and the climate. We prefer to halve the current level of CO2 worldwide. We also want biodiversity to improve. These are many goals but they can go together, as a study by the World Resource Institute shows.

In the report ‘Creating a Sustainable Food Future‘, the WRI investigated how we can simultaneously meet development, climate, and food supply and nutrition goals. It recommends “making full use of every hectare of pasture worldwide that is suitable for sustainable intensification and has the potential to multiply milk or meat production.”

Since livestock feeds on rainwater, food waste, and inedible food such as meadow grass, this has major advantages for the food supply and climate, especially given the high nutritional value of meat. This recommendation is of the utmost importance in view of the increase in the world population, the expected rise in income in middle-income countries.

Meat is badly needed to meet the increasing demand for good nutrition in countries where little meat is eaten per capita, the case in most developing countries.

The WRI in the same report also recommends limiting meat consumption in countries that consume far above average, such as the US, Australia, and Argentina. But mainly to level off the growth in demand and thus limit it to the use of land that would also be less suitable for arable farming; to reduce the use of animal feed from crops that are also edible for humans, or to limit the expansion of pastureland, resulting in deforestation and loss of biodiversity. Instead of investing a lot in campaigns now, one needs to recognize that the rising desire to eat meat in middle-income countries will not automatically lead to growth in demand as it is likely to be dampened by additional price increases (price elasticity plays a key role here).

There is little point in painting meat as a bad product per se, because that is not right. Meat is nutrient-rich and becoming a vegetarian is certainly not a necessary climate policy recommendation.

Sustainable economic development worldwide appears to be a good starting point for propagating our high production standards to the rest of the world. In the rich countries, especially in northwestern Europe, animal husbandry is very efficient, the farmers are highly productive, use little land and the products have relatively little impact on the climate, and animal welfare is good. Improvements are constantly made because consumers demand less climate impact and better animal welfare.

Meat could also be produced elsewhere in the world with the same efficiency not excluding future innovative adaptations and increased productivity via local technology research and development.

During that trajectory towards global prosperity, meat substitutes will hit the market and will certainly help to level off the rise in demand for real meat, especially in industrially processed foods such as pizzas and ready meals.

By focusing exclusively on less meat consumption, we miss an opportunity to work on prosperity for everyone.

————-

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.— In the Featured Photo: Dairy cattle in the Netherlands. Photo provided by the author.