- In the wake of this new shift in oil prices, countries that rely heavily on exporting crude oil are beginning to feel their budgets tighten.

- To stave off unemployment and possible social unrest, some states are taking drastic measures to increase control on their black lifeblood, while other nations are forming unlikely alliances in the hopes of controlling prices.

The other day I pulled into my local Mobil station in west Los Angeles and filled up my Ford Focus for a satisfying total of $27.23. A year ago that bill would have been closer to $40.

So what happened? Why am I benefiting at the pump while my father is pulling the few remaining strands of his hair out whenever he checks his oil stocks?

The answer is surprisingly simple: too much supply. Countries such as Russia, Iraq and Nigeria have flooded international markets with a black sea of fresh crude. Other nations including Canada and the United States are also becoming net exporters with new horizontal drilling techniques.

Less demand for oil is also contributing to the two-decade low in oil prices. Europe’s economic woes of late are stifling demands for Russian oil. Conversely, emerging economic powers such as India and China are forcing oil producers to compete, lowering their prices even further. In addition, some countries are more environmentally conscious and are making concentrated efforts to lessen their carbon footprints.

In the wake of this new shift in oil prices, countries that rely heavily on exporting crude oil are beginning to feel their budgets tighten. To stave off unemployment and possible social unrest, some states are taking drastic measures to increase control on their black lifeblood, while other nations are forming unlikely alliances in the hopes of controlling prices. This article focuses on four different oil-exporting countries as they attempt to adapt to a world that is seemingly drowning in oil.

Saudi Arabia

When the Arab Spring erupted across much of the Middle East in 2011, some outsiders were surprised that Saudi Arabia, one of the most socially conservative and traditional states, appeared immune to even a flicker of political discontent within its borders. The silver bullet to preventing political reform, as it turned out, was money. With its immense oil wealth and a seemingly endless supply of crude beneath its desert sands, the Saudi government was able to appease its people with high-paying government jobs, free health care and cheap utilities without a single tax.

As oil prices have plunged from $100 a barrel in June of 2014 to around $30, the royal family is considering once unthinkable measures in order to fund the government and diversify its economy.

“There is an issue with the sustainability of the economic model in Saudi Arabia, and the oil price can be seen as a wake-up call,” said Fahad Alturki, chief economist at Jadwa Investment.

Defense Minister, and heir to the throne, Prince Mohammed is said to be considering economic reforms in order to fund the government in the medium-to-long term. Though specific details are limited, the government may implement taxes on undeveloped land and consumer goods. A price increase on electricity and water is also on the table.

Another major reform is the possible privatization of the country’s state-run oil company, Saudi Aramco. The company, which turns over 90 percent of its revenue to the government, is the world’s largest — with an estimated reserve of 261 barrels. For comparison, Saudi Aramco is ten times larger than Exxon-Mobil, which has a $314 billion evaluation.

In the Photo: Defense Minister and heir to the throne Prince Mohammed is seeking to raise revenue for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen and other government expenses. Photo Courtesy: Tribes of the World via Flickr.

However, it is unlikely that the government would privatize the entire company out of fear of revealing the company’s true worth. “I think they would never list the full company,” said Valerie Marcel, an independent energy consultant. “The government would not want those finances to be exposed.”

Regardless of what option the Saudi government ultimately takes, the state faces serious economic challenges as an estimated 250,000 youths enter the workforce every year. More than half of the country’s 30 million people are under the age of 25 and have benefited from the state’s generous austerity programs and jobs for much of their lives. If the government is forced to roll back on these perks while unemployment continues to climb higher—unemployment is currently at 12 percent — then the ruling royal family may face serious social and political challenges down the road.

Russia

One solution that many oil-exporting countries are beginning to flirt with is a coordinated cut in supply between all the major exporters. It’s a simple fix in theory that a student would learn in his or her high school economics class: supply goes down, prices go up. What’s most surprising is that the proposal is coming out of Russia.

Related articles: “OIL SPILLS: A DOUBLE-STANDARD WORLD“

Igor Sechin, the chief executive of the state-owned Rosneft, openly discussed the new strategy in February. Estimating an oversupply of 1.5 million barrels per day of crude, Sechin proposed that all major exporters reduce their output by half-a-million bpd.

“A coordinated supply cut by major exporters by around 1 million barrels per day would sharply reduce uncertainty and would move the market towards reasonable pricing levels,” Sechin said at the International Petroleum Week conference held in London last month.

Although Sechin is a known ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, he failed to suggest whether the Russian government would approve of the plan. At the time that this article was written, Putin had not commented on the proposal.

Even without President Putin’s approval, the plan for a coordinated cut on oil exports was quickly embraced by Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Venezuela. A possible union between Russia and Saudi Arabia is particularly surprising as the two countries have been long-time geopolitical rivals. Russia has drawn criticism from Saudi Arabia and other nations in recent years for its support of President Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian Civil War, while Russia has historically been opposed to OPEC.

In spite of their political differences, however, the four countries insist on moving forward only if other major exporters join, which could prove troublesome for their shaky alliance. Iraq, for instance, insists on maintaining its policy of increasing oil production. Meanwhile, Iran also aims to increase exports after seeing its sanction lifted in the last year’s nuclear agreement.

Economists and analysts, nonetheless, remain skeptical of the plan. “The market does not need a freeze,” said Michael Lynch, president of Strategic Energy and Economic Research. “It needs a reduction.”

Other critics argue that oil exporters are generally adverse to cutting production. By doing so, these countries would risk losing their market share, which can be difficult to regain after prices have stabilized later.

In the Photo: Russian oil tanker Volgoneft-250. Russia is considering reducing its oil exports to raise prices. Photo Courtesy: Pete via Flickr.

For the moment, the Russian economy remains in a severe recession. Since 2014, the ruble has fallen to 0.013 USD, banks are closing at alarming rates and recent projections have the economy contracting at an annual rate of 3.7 percent.

Despite the poor economic climate, President Putin remains confident that Russia will prevail economically and abroad. On the Russian streets, there is a surprising lack of protest or vocal demands for reform. Author Massa Gessen in her NYT op-ed argued that this could be the byproduct of a censored media environment and restricted lines of communication: “Russian television alternates between uplifting stories about growing domestic production, Russia’s boundless resources and fear-mongering reports about United States’ aggression toward Russia.”

It’s unclear how long the Russian government can keep up the ruse. After all, 25 years ago the Russian people ultimately took to the streets to demand the end of the Soviet system after decades of economic regression. The jury remains out on how many more years of a similar economic glum it will take this time around for Russians to once again call for reform.

Iran

Following the lifting of sanctions last year, the Iranian government under President Hassan Rouhani declared that it planned to achieve 8 percent growth for 2016. However, with oil prices dipping ever further downward, more and more Iranians are increasingly concerned about just how far their newly liberated oil reserves can take them into the future.

The nuclear agreement between Iran and the international community should still be seen as a tremendous step forward for most parties. According to Voice of America, sanctions had cost Iran $160 billion in oil revenue since 2012, causing the Middle Eastern country’s economy to shrink by 20 percent.

In 2013, the election of the pragmatic President Rouhani promised a more liberalized approach to economics and a more cooperative approach to Western powers. Rouhani’s “save the economy, revive morality and interact with the world” platform turned out to be more than optimistic political rhetoric as he and other Iranian officials were able to successfully negotiate an end to sanctions the following year.

Iran was able to increase its oil production by 3.7 percent, or 100,000 bpd, in just the first month after sanctions were removed, according to analysts at Bloomberg. The same projections now indicate that 400,000 bpd production is now feasible after six months.

Iran’s open gates have also attracted an influx of foreign investment. The Iranian Mines and Mining Industries Development and Renovation Organization recently joined with Italian steel producer Danieli on a $2 billion project. In addition, France’s PSA Peugeot Citroën invested more than $400 million in Iran Khodro, an Iranian automaker.

Although good news for the Iranian government, many Iranians are concerned that the flood of new investments into the country is overwhelmingly concentrated in higher-level state-sponsored companies with little of the new wealth trickling down to smaller businesses.

“We are not getting any credit, inside or outside of the country,” said Bahman Esghi, the secretary general of the Tehran Chamber of Commerce. “We can’t make transfers and the government has other priorities.”

So far it appears that many foreign companies just aren’t willing to take the risk when it comes to investing in smaller Iranian companies. Other analysts claim that only larger Iranian organizations are currently capable of utilizing the $50 billion in investment that the Middle Eastern country requires every year.

“Our bigger companies are our top priority,” said Amin Amanzadeh, an Iranian financial reporter. “They are the only ones who can handle foreign investment. Also, if they improve the whole economy will.”

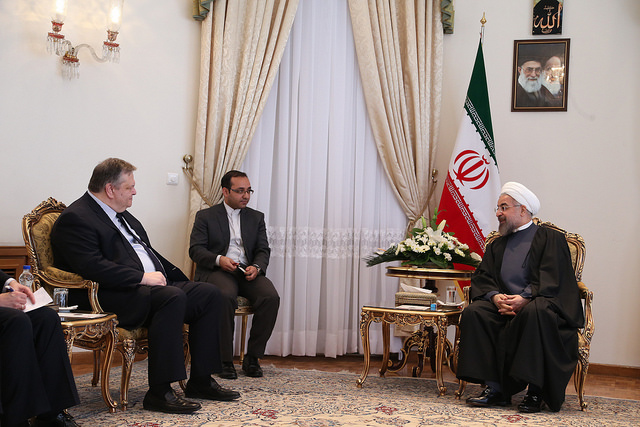

In the Photo: President Rouhani meets with former Greek Deputy Prime Minister Evangelos Venizelos in March of 2014. Photo Courtesy: Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών via Flickr.

The new foreign investments may not be enough, however. With oil prices hitting historic lows, many analysts insist that the Iranian government must ultimately liberalize its economy in order to achieve the growth that President Rouhani and other reformers had promised.

In July of 2015, a survey conducted by Gallup found that only 52.8 percent of Iranians believed that their nation was on a positive path. While this remains the majority opinion, albeit slightly, this level of confidence has dropped significantly since 2012 when the poll found that seven in ten Iranians were more upbeat about their future.

Putting that study aside, Iranians overwhelmingly approved of President Rouhani’s moderate party in last month’s parliamentary elections. Although conservatives continue to control the state’s judiciary, Rouhani’s allies seized control of the capital’s delegation, establishing a strong minority faction. Pragmatists also took some seats in the Assembly of Experts elections, which may oversee the succession of the next supreme leader.

It’s not hard to imagine that if enough wealth is able to trickle down from foreign investments while oil production keeps many Iranians employed, the Islamic republic may slowly transform from the radical pariah state that characterized the country for much of the last quarter-century into a successful Middle Eastern economic hub.

Venezuela

It’s hard to find an oil-producing country closer to the brink than Venezuela. Reporters crossing the country have documented shortages in water, medical supplies and other basic goods. With inflation expected to hit 720 percent, a New York Times journalist recorded instances of seeing people carrying large bags of money in order to purchase bare necessities on the black market.

Faced with such an economic crisis, the Venezuelan Supreme Court approved a decree in February granting President Nicolás Maduro expansive emergency financial powers. “Now that the emergency decree is in place, I’m going to put in place a set of measures in the coming days that I was already working on,” Maduro said in a statement.

Maduro wasted no time in flexing his new economic powers. The military quickly set up a new state company tasked with overhauling the oil industry. According to the official press release, the new government entity will work to maintain wells, invest in new fuel storage tanks, expand drilling and assist with transportation of oil and other materials.

In the Photo: A presidential campaign mural promoting Nicolas Maduro. Photo Courtesy: Joka Madruga via Flickr.

With the benchmark dollar falling and the country teetering ever closing to defaulting on its debt, the Venezuelan government aims to increase mining activities in the hope of attracting more foreign currency earnings. Latinvest partner Russ Dallen recently stated that the newly formed military company might be an effort to shield oil revenue if the state’s oil company—or the government itself—were to default.

The new decree is not popular in many sectors of the government. Venezuela’s parliament, which is controlled by President Maduro’s opposition, rejected the decree outright when he first proposed it in January. “It’s the duty of the national government to promote the creation of state companies that adjust to the new mode of management,” the decree states. “The state must guarantee a model of productive eco-socialism, based on a harmonious relation between man and nature.”

One of the chief arguments against President Maduro’s decree is the concern of increased militarization throughout the South American country. “In 2016, one of the scenarios we’re expecting is the increased militarization of the country,” said Rocio San Miguel, director of Caracas-based non-profit Citizens’ Control. “It’s a means to satisfy the military sector. Without doubt, it’s a gesture of loyalty to the revolution.”

Desperate times certainly call for desperate measures, but in the case of Venezuela it may be a question of just how far the government is willing to go in order to salvage what is left of its sinking economic ship.

In an increasingly globalized world, it’s crucial for all parties to understand the impact of commodities prices, such as oil in this case. It’s all too common for economists to focus solely on the financial impact of oil price fluctuations, or for international relations analysts to imagine the long-term evolution of geo-politics. Intellectuals mustn’t forget that the societies, and the planet they inhabit, have stakes in the game as well.