Despite sanctions and numerous official condemnations from leaders in the West, the objective of isolating Russia has not been achieved and the end of the war is not in sight. With dire consequences for the whole planet, as war, especially a prolonged one, beyond the tragedy of human losses, adds to both environmental degradation and climate change.

The longer the war, the more climate change will accelerate.

Isolating Russia economically and diplomatically was a goal that made sense, giving hope that the war could be ended soon. But even the United States, a leader in imposing sanctions on Russia – always the first to come out with new sanctions and always more extensive than any imposed by the EU – is breaking down on its resolve to isolate Russia.

On Friday, July 29, there was a phone call between US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov about American detainees and Ukraine. Blinken would not discuss what was specifically said but he indicated that he had pressed Lavrov to accept a “substantial proposal” for the release of jailed Americans Paul Whelan and Brittany Griner.

According to the Russian Foreign Ministry, Lavrov “strongly suggested” to Blinken “returning to a professional dialogue in the mode of quiet diplomacy” on any efforts at American detainees’ release.

Russia’s continued presence around the world is sustained by Putin’s and Lavrov’s diplomatic moves

Putin has been remarkably clever at leveraging the world’s need for Russia’s grain, advancing Russia’s position as a global power; meanwhile, his diplomacy chief Lavrov has been doing a splendid job giving him diplomatic support, in particular with extensive travels through Africa, the area most at risk of grain shortages and hunger crises.

On July 19, Putin met with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Teheran to discuss several matters (including Syria) and shake hands over the just-concluded grain export deal, in principle allowing Ukraine to ship out its grain from Odesa across the Black Sea and the Turkish Dardanelles strait.

At the time of writing, Russia continues to bomb Ukraine’s southern region, including Odesa, raising serious doubts over Putin’s commitment to respect the deal.

The next few days found Lavrov busy traveling across Africa.

On July 24, he was in Cairo, Egypt, meeting with General Ahmed Aboul Gheit, the Secretary General of the Arab League, the oldest regional organization in North Africa and the Middle East, formed in 1945 initially with six members: Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan (renamed Jordan in 1949), Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Today the League has 22 members, extending from Morocco to Yemen. All member states are also members of the OIC, the Organisation for Islamic Cooperation.

On July 25, he was in Brazzaville, Congo, meeting with Congo’s President Felix Tshisekedi to whom he delivered a message from Putin.

Only July 26, he was in Entebbe, Uganda, meeting with Ugandan President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni.

On July 27, he was in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, meeting with Ethiopian Deputy Prime Minister Demeke Mekonnen.

And so it goes.

But it’s not just a matter of traveling around and collecting photos of handshakes. Taking advantage of the next BRICS meeting that will take place in 2023 in South Africa, Russia has announced its support for expanding the BRICS alliance with five new members. They include Egypt, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia which have already placed their candidacy, and, as announced by the Russian Tass agency on June 28, Iran and Argentina.

Those five countries are clearly slated to become Russia’s best friends – at least, in Putin’s and Lavrov’s plans.

Yet there is no question that the sanctions have started to hurt.

Sanctions are causing a slow economic collapse in Russia

A new study from Yale University’s Leadership Insitute (published July 19) measuring Russian current economic activity five months into the invasion of Ukraine makes the case that the withdrawal of big Western brands from Russia and the sanctions have indeed “catastrophically crippled” the Russian economy.

Their findings are based on extensive evidence gathered using “private Russian language and unconventional data sources including high-frequency consumer data, cross-channel checks, releases from Russia’s international trade partners, and data mining of complex shipping data.”

Thus, it no doubt constitutes one of the first and most reliable comprehensive economic analyses of Russia’s evolving economic situation.

In particular, the study shows that:

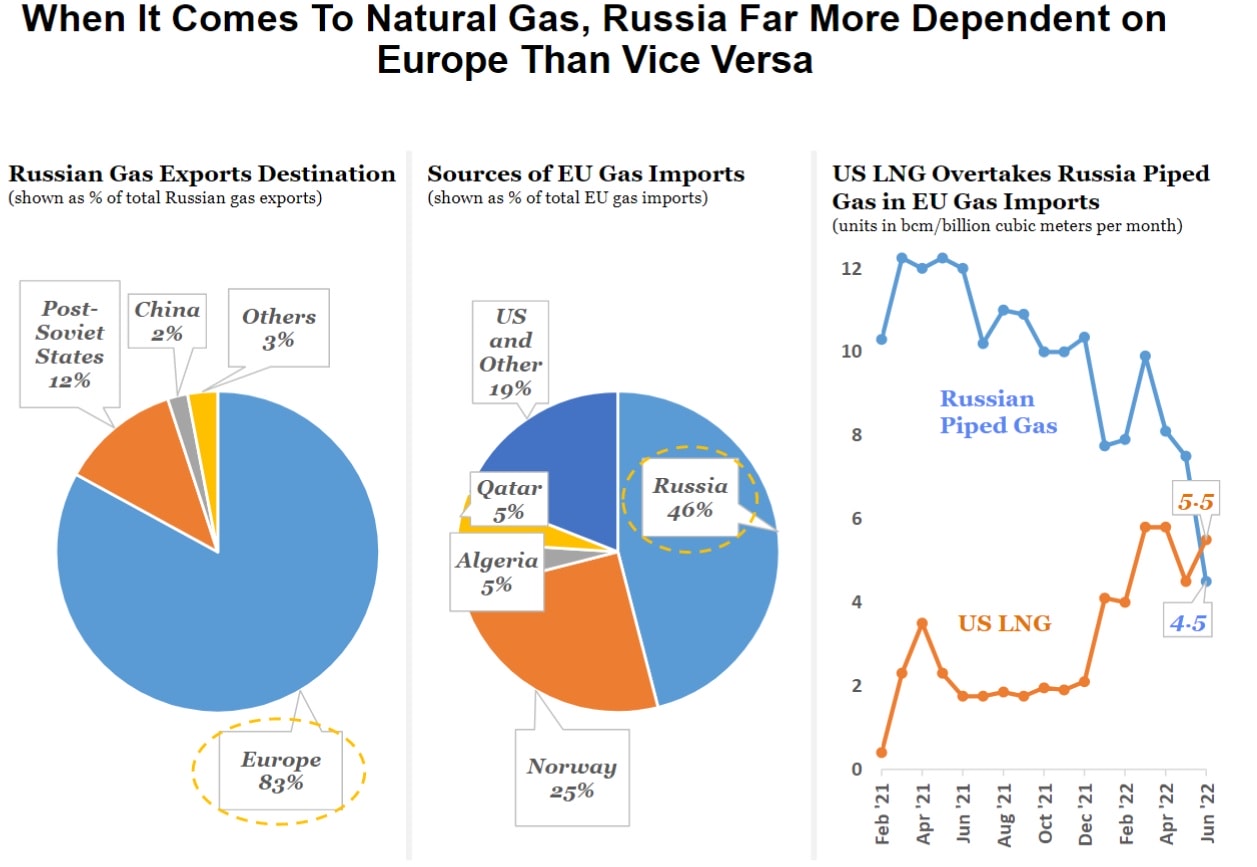

– Russia’s strategic positioning as a commodities exporter has irrevocably deteriorated and faces steep challenges executing a “pivot to Asia” with non-fungible exports such as piped gas;

– Despite some lingering leakiness, Russian imports have largely collapsed, and the country faces stark challenges securing crucial inputs;

– Despite Putin’s delusions of self-sufficiency and import substitution, Russian domestic production has come to a complete standstill; the hollowing out of Russia’s domestic innovation and production base has led to soaring prices and consumer angst;

– As a result of the business retreat, Russia has lost companies representing about 40% of its GDP, reversing nearly all of three decades’ worth of foreign investment;

– Putin is resorting to unsustainable fiscal and monetary policies, which has already sent his government budget into deficit for the first time in years and drained his foreign reserves even with high energy prices.

The Yale experts argue that Kremlin finances are in “much more dire straits than conventionally understood,” and the outlook is grim as Russian domestic financial markets are “the worst performing markets in the entire world this year despite strict capital controls.”

Moreover, as Russia is “substantively cut off from international financial markets,” its ability to tap into the funds needed to revitalize its economy is severely limited.

Perhaps the single most striking finding of this study is that when it comes to natural gas, Russia is far more dependent on Europe than vice-versa, as the following diagram shows (screenshot):

While there is no question that sanctions are hitting Russia’s economy, in the long run, it is not clear how “crippled” Russia’s economy might become. Putin’s economic strategy includes setting out to develop new trade routes and new commercial partners.

A particularly promising new route, according to DW, would be to Mumbai, India, via Azerbaijan and Iran. While all this is far from certain, it could still mean, over time, as suggested in the following video, Asia’s gain and Europe’s loss:

For now, the ruble is soaring as a result of the war and spike in oil and gas prices and Putin’s war chest is full to the brim, allowing him to continue military operations unimpeded.

As Simon Jenkins, a UK Guardian columnist argues “…the west and its peoples have been plunged into recession. Leadership has been shaken and insecurity spread in Britain, France, Italy and the US. Gas-starved Germany and Hungary are close to dancing to Putin’s tune. Living costs are escalating everywhere. Yet still no one dares question sanctions.”

Even the impact on the Russian people so far has been minimal as they play in the hands of Putin’s propaganda. One of my Russian-speaking friends who follows the news inside Russia told me she was amazed by the effectiveness of the propaganda.

“The worst is that they are simply brainwashing their population about the war and sanctions,” she said, adding that “most of these people have no idea about what damage these sanctions will bring to their economy in the long-term. They believe they just lost big brands, that can be replaced by the local ones and that this is the only problem they got.”

McDonald’s has left and been replaced by a Russian-owned chain called Vkusno & tochka (“Tasty and that’s it”). That’s it, indeed. But Russians are historically used to being mistreated by their government.

While Putin is winning, for now, his eventual defeat is likely but at what cost?

There is no question that sanctions are hurting Europe too, slowing the economy and hurting the green transition. As Stanley Reed reported in the New York Times, Europe is “on a knife’s edge” in its race to secure natural gas sources.

So far, the race has been fairly successful. Despite Gazprom’s cutbacks, gas supplies in Europe in the first half of 2022 have been roughly equal to those of the same period last year, according to Jack Sharples, a fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Europe has stored gas reserves up to about 67% of overall capacity, more than 10 percentage points higher than a year ago. Prospects are now good that European countries might come close to the EU Commission’s target of 80% full before winter.

Yet people are still concerned as Russia continues in its gas war against Europe and unforeseen weather events – such as an unusually cold winter – could upset the applecart. As a result, European gas futures prices have doubled in the last two months to about 200 euros a megawatt-hour on the Dutch TTF exchange – that’s about 10 times the levels of a year ago.

The upshot: The green transition is at risk, and climate change accelerates

Sanctions were always a risky path to follow because they take time before any impact is perceptible and there are numerous perverse side-effects that hurt the “sanctioner” nearly as much as the “sanctioned.”

And with Putin’s war chest full, the war is set to last a long time – long enough for all the negative collateral effects on the climate to develop and accelerate global warming. Because the green transition in the one continent ahead of all the others on this issue – Europe – is stopped in its tracks.

On June 8, the EU Parliament failed to pass a range of “Fit for 55” proposals to achieve EU climate goals that include independence from Russian energy. This happened as a result of conservative-led efforts to water them down, thus weakening the EU green transition.

In particular, it led to the postponement of the proposed reform of the EU’s carbon market, of the introduction of a carbon border tax, and the establishment of a Social Climate Fund as demanded by the EU Commission in the “Fit for 55” package.

Since then, many of the world’s largest economies, including Germany, are returning to coal power. On July 8, Germany’s upper house of parliament gave final approval to reactivate coal plants that had been mothballed and other European countries are following suit – all saying these are temporary measures. But how “temporary” are they likely to be?

Expect the whole planet to suffer. That is what happens when a major petrostate like Russia carries out a war in a globalized world. Kock-on effects cannot be stopped, and climate change accelerates.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: This photo dates to January 8, 2020, when Vladimir Putin met with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Istanbul. It could have been taken on July 19, 2022, when Putin once again met with Erdogan over the grain export deal. NATO – Turkey is a member – no longer views Russia as a friend but the handshake was the same. Source: Wikimedia commons