The new WWF report, “Analysis of the Implications of Deep Seabed Mining for the Global Biodiversity Framework and the Sustainable Development Agenda,” highlights the potentially irreparable damage that deep seabed mining (DSM) could have on marine biodiversity, climate regulation, and sustainable development. The report assesses the threat that DSM poses by aligning with the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) and the agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

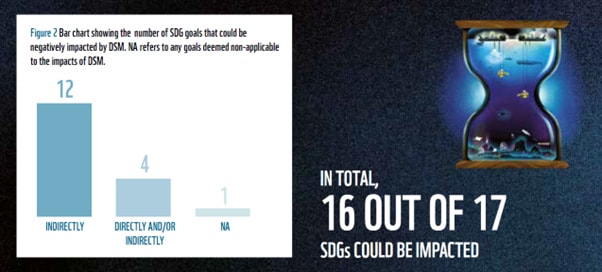

According to WWF’s report, almost all of the 2030 GBF targets and SDGs are at risk of being compromised by deep seabed mining. In total, 18 out of 23 GBF targets and 16 out of 17 SDGs could be negatively impacted, making DSM an unsustainable choice in the green transition.

What is deep seabed mining?

Deep seabed mining involves the extraction of minerals from the deep seabed (200 metres or more). The deep sea remains vastly unexplored — as a recent report estimates, only about 2-3% of the seafloor has been explored.

The global shift to meet climate goals has resulted in a new demand for critical minerals. The minerals of interest include cobalt, lithium, copper, and nickel, which are essential to produce clean energy technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles.

Although deep seabed mining may intend to support clean energy production, this well-intended method of extraction will instead lead to a multitude of devastating environmental results. From destroying deep-sea habitats and harming fisheries to exacerbating social and economic inequalities — this report demonstrates the need to pause deep seabed mining practices.

What are the risks?

Biodiversity loss

Deep seabed mining methods of extraction (as currently practiced) are extremely physically destructive as they remove and disturb areas of the deep seafloor that are home to numerous ecologically significant and endemic species (i.e., not found anywhere else in the world).

Deep seabed mining would cause severe and direct destruction of seafloor habitats, with long-lasting effects on deep sea communities that recover extremely slowly. To what extent the deep sea can recover from deep seabed mining disturbances, if at all, is unknown.

Using DSM would introduce several pollutants. For instance, copper, which would enter the water column from mine waste, is highly toxic to marine organisms and its effects can be fatal. DSM will depend on a lot of heavy infrastructure, which increases the risk of oil spillages and other types of pollution that derives from large vessels and increased marine traffic (e.g., noise, light, microplastic, and heavy metal pollution from paint).

Fisheries and fish stocks

According to WWF’s report, DSM infrastructure will directly damage fisheries, subsequently affecting livelihoods that depend on fisheries for income, economic stability, and food security, such as in Pacific SIDS (Small Island Developing States).

The majority of SIDS close to (or within) current exploration contracts rely on fishing. The report states that fish products account for roughly 70% of the exports of SIDS. The industry supports many livelihoods, creating permanent employment.

However, there are legitimate concerns about the potential impacts of DSM on fisheries in these SIDS, particularly stressing the impact of heavy metal contamination of economically vital tuna stocks. Tuna fisheries in Pacific SIDS are reported to account for approximately 84% of GDP by WWF’s report, making this a critical issue.

Deep seabed mining may exacerbate the effects of climate change

WWF warns that DSM threatens the ocean’s role as a major carbon sink, which stores 25% of carbon emissions. As the ocean is the planet’s largest carbon sink, DSM is expected to disrupt the ocean’s ability to sequester carbon and mitigate against the effects of climate change.

Undisturbed deep sea sediments sequester carbon for millions of years. However, the WWF report claims that DSM vehicles are estimated to disturb roughly 172.5 tons of carbon per km² mined per year, surpassing the natural sequestration rate of about 14 kg per km² in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

Related Articles: You Can’t Mine the Seabed Without Proper Rules | Deep-Sea Mining: Disaster for the Planet or Sustainable Solution? | France to Ban Deep-Sea Mining: What It Implies, and Why It’s Important | Landmark High Seas Treaty Agreed, Ushering in New Rules for Two-Thirds of the Ocean

Increased disparities between the global north and global south

The WWF report argues that DSM would likely exceptionally benefit multinational corporations from the Global North, leaving local capacity underdeveloped. As DSM is projected to supply only about 8% of global cobalt by 2050, there are doubts about its profitability and viability.

Pacific SIDS — already limited by expected climate change effects, as well as legal and institutional frameworks — face heightened risks in managing DSM’s environmental and economic impacts. WWF demonstrates this by highlighting the case of Papua New Guinea:

“When Papua New Guinea, was left with a debt of USD 125 million after Canadian mining company Nautilus went bankrupt, having been the first recipient of a DSM exploration licence.”

The report stresses that without extensive joint scientific research, technology transfer, and capacity-building initiatives, DSM is expected to widen disparities between the Global North and South.

Cultural infringements

For many indigenous peoples and local communities, the ocean represents significant cultural, historical, and spiritual value. DSM threatens this cultural significance by taking advantage of the ocean’s natural resources in a destructive way.

WWF presents the example that “parts of the Atlantic Ocean are considered memorials for those who died and, indeed, survived during the transatlantic slave trade. UNCLOS mandates that State Parties are obligated to protect historically significant objects.”

So what can be done about deep seabed mining?

WWF has called for a science-based moratorium on deep seabed mining at the International Seabed Authority (ISA) during the March Council meeting, urging governments to uphold the precautionary principle and prevent irreversible damage to the deep ocean. The lack of transparency in regulatory frameworks, as well as the lack of scientific understanding of deep-sea ecosystems, makes proceeding with deep-seabed mining a reckless gamble.

Jessica Battle, lead of WWF’s No Deep Seabed Mining Initiative, said:

“The deep sea is one of the last untouched ecosystems on Earth, playing a crucial role in regulating our climate and supporting marine life. We cannot afford to sacrifice it for short-term commercial interests. Deep-seabed mining must not go ahead until the environmental, social and economic risks are understood, all alternatives to deep-sea minerals have been explored and it is proven that deep-seabed mining can be managed in a way that protects the marine environment and prevents biodiversity loss and climate impacts, habitat degradation and species extinctions. Until then, a global moratorium on deep seabed mining is needed.”

Calls for a moratorium are increasing, with local and international NGOs, community leaders, scientists, governments and fishers’ organizations leading the way. The United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative has warned of significant reputational, regulatory, and operational risks associated with plans to mine the deep seabed.

The journey to a more sustainable future begins with a simple decision: Pause deep-seabed mining.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: Illustration of a deep sea mining machine for the retrieval of minerals and deposits from the ocean floor found at depths of 200 metres up to 6,500 metres. Cover Photo Credit: © Jack Cowley / Greenpeace.