According to a Reuters report last week, a United Nations agency, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) which governs deep-sea mining, will start accepting applications in July from companies that want to mine the ocean’s floor in international waters. This apparently anodyne decision could have dramatic consequences for the health of our oceans and yet the news arrived, almost unnoticed, despite its potential for triggering yet another environmental catastrophe.

Why this news has remained under the radar is not entirely clear, but it’s likely the result of the usual private sector’s cover-up strategies: Deep-sea mining is clearly in the interest of the global mining industry. Undoubtedly industry lobbies are pushing to keep the lid on the news as long as possible, until the deed is fully done this coming July.

Reportedly, during the ISA debates last month, a German delegate openly accused the ISA Secretary-General Michael Lodge, a British lawyer, of having abandoned ISA neutrality and its mandate to protect marine resources, allowing commercial pressure to open the door to mining permits.

As the above video makes abundantly clear, the ISA approval process (in the hands of not its governing Council but a committee, the Legal and Technical Commission or LTC) is not transparent as the LTC is not required to explain to the Council its decision to approve (or not) applications for commercial exploitation permits — and so far, it appears to have regularly approved all applications.

In addition, there is, built into the approval process, a temptation to approve all applicants as they have to pay the ISA $500,000 for a permit, a sum that goes a good way to keep the ISA budget afloat.

The monitoring and administrative capacities of the ISA are also at stake here: Granting mining permits is only a first step and an easy one. Given its mandate to protect the oceans, the ISA should also have the capacity to engage in monitoring mining activities in remote sea areas (both challenging and costly) and correctly assess ecological damage when and if it occurs; and finally slap on appropriate fines for the damage to the perpetrators, both the private companies and states sponsoring them.

A tall order for any UN agency, but especially for the ISA which is a small UN entity; worse, like all UN agencies it has no legal enforcing power, it can only get things done by gathering support from Member States.

Let’s take a closer look at what is going on here, and what happens if we open the door to deep-sea mining.

Has the ISA succumbed to private sector pressure?

The decision to grant permits came after the U.N. body spent two weeks in March hotly debating standards for this new and controversial practice. Some countries such as Chile, France, Palau and Fiji manifested opposition, calling for a global moratorium on the practice, citing environmental concerns and a lack of sufficient scientific data.

The process began two years ago, when the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru notified ISA of its plans to start deep-sea mining, giving it two years — fast-tracking an ISA rule — to complete long-running talks on rules governing this new and highly controversial industry.

Why Nauru engaged in this exercise of pressuring a UN agency is easily explained: As Reuters points out in its report, Nauru President Lionel Aingimea simply notified ISA about the mining plans to be carried out by a subsidiary of The Metals Co in a letter dated June 25, 2021.

The Metals Co, on its website, has no doubts that it can handle the environmental threats of deep-sea mining and that, compared to land mining, it is a win-win. While acknowledging that the carbon footprint for land-based mining can be improved, it argues that in most cases, “it will always be much worse” than deep-sea mining, dredging up polymetallic nodules simply because the “starting point for the nodule resource is fundamentally different: rich concentrations of four metals in a single rock; an entirely usable rock mass; a barren and common, desert-like environment with limited life; and no threat to Indigenous land.”

And the Metals Co assures that its adaptive management system, “a mix of deep-sea ecological data, marine sensors, and cloud-based A.I.”, will enable them “to monitor what’s happening in real-time” and “adapt operations” to “stay within expected ecological thresholds”.

Reassuring words, but can they be believed? Monitoring impact on the environment is fine, but how can we be sure they would know how to “adapt operations” once disaster strikes? Can we entrust the future of our uncontaminated sea beds to big corporations wedded to profit-making and notoriously unconcerned by the environment?

Deep sea mining: Where it stands now and where it is headed

Today, sustained sea-mining operations have overwhelmingly occurred in water depths no greater than 200 metres, as the “most significant” sea mineral deposit beds lie near coastlines and are thus placed under national jurisdiction. And many countries are lax in applying regulations or don’t even have any regulations regarding mining in their EEZs.

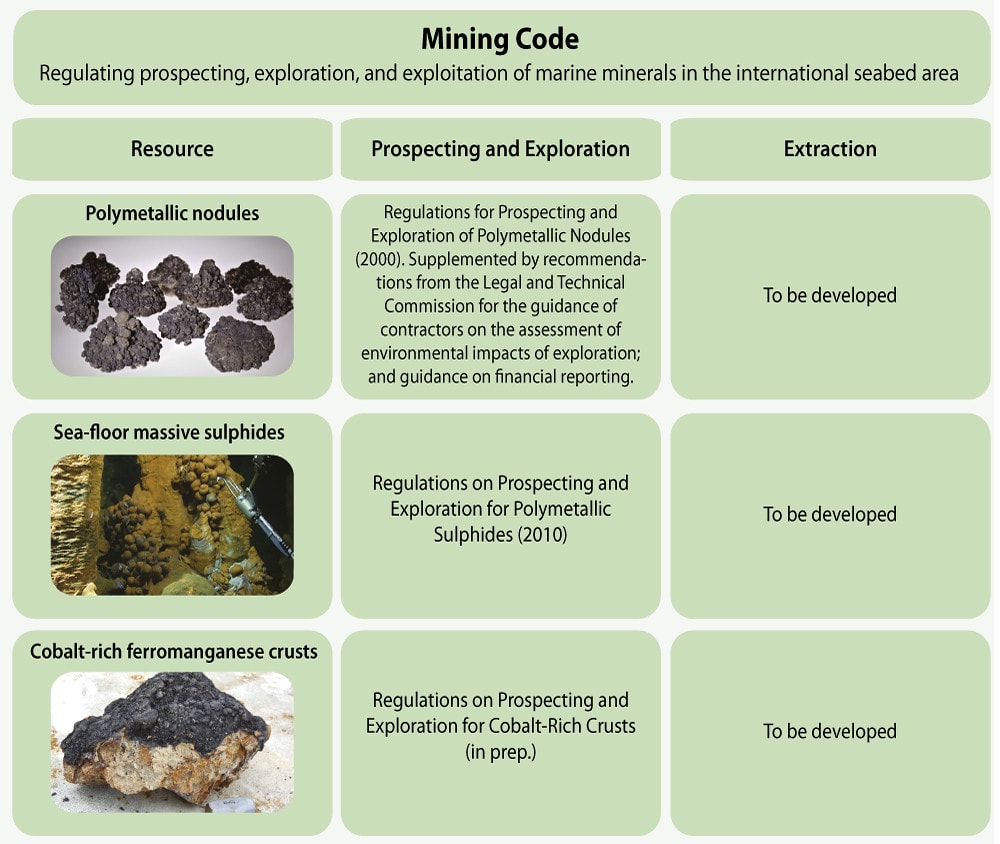

But even if today there’s no mining of deep-sea beds, the stage is set: Exploratory activities have been ongoing for years and ISA has already issued permits for exploration, thirty as of January this year.

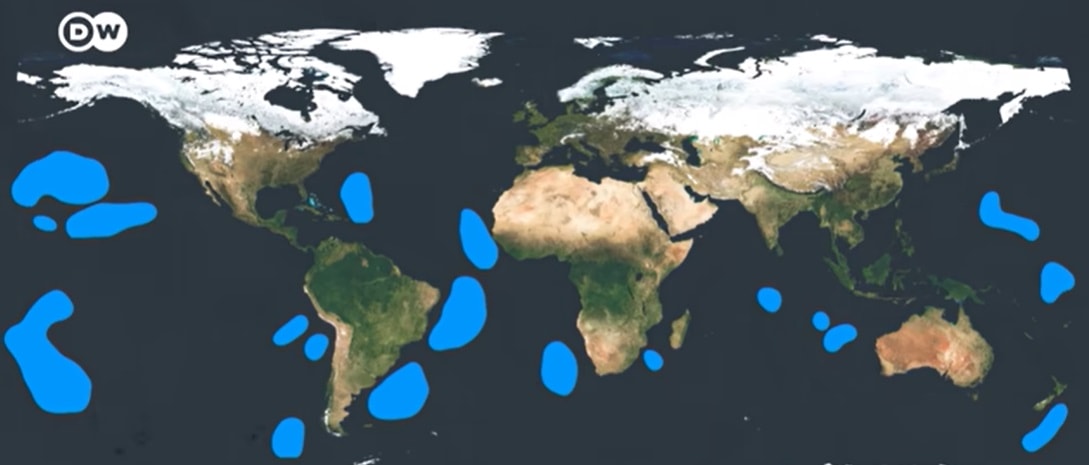

Nineteen of these contracts are to explore for polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, Indian Ocean and Western Pacific Ocean. There are seven contracts for polymetallic sulphides in the South West Indian Ridge, Central Indian Ridge and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and five contracts for cobalt-rich crusts in the Western Pacific Ocean and the South West Atlantic.

Of the 30 contracts issued, at least eighteen are held by only seven countries – China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Russia and South Korea – through their state-owned companies or government agencies and ministries. Another seven contracts are effectively in the hands of three private companies: The Metals Company (formerly known as DeepGreen), a privately held Canadian company; UK Seabed Resources, a subsidiary of US based Lockheed Martin; and Global Sea Mineral Resources, a subsidiary of the Belgium company DEME Group.

Thus, the presumption is that mining industry lobbies exist and probably operate at ISA meetings, “behind the delegates” of all the above-mentioned UN Member States. This turn of events — allowing permits for commercial exploitation — certainly marks a low point in the history of ISA, an emanation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the UN sea treaty intended to defend and preserve marine resources and environment for the “common good”.

Why ISA’s role is key

ISA came into existence in 1994 and became operational in 1996, with headquarters in Jamaica. And as of 1 May 2020, ISA has 168 Members, including 167 Member States and the European Union.

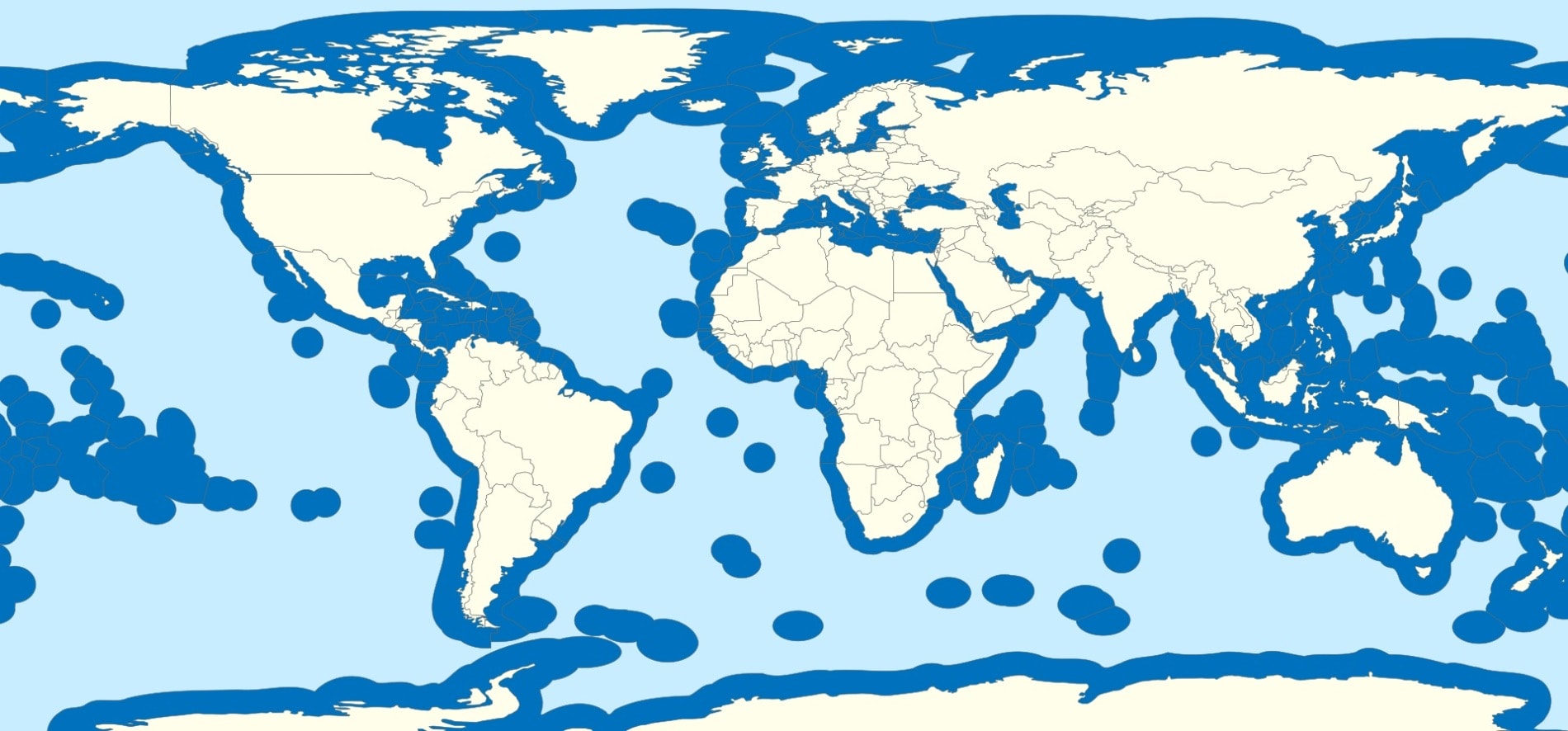

Let’s be clear: ISA is a unique UN agency with a mandate over what it calls “the area”, around 54 percent of the total area of the world’s ocean. It is tasked to preserve it for the whole of humanity. The ISA also promotes marine scientific research and conducts training programs, seminars, conferences and workshops on scientific and technical aspects.

The rest of the oceans are under national jurisdiction, the so-called EEZs (exclusive economic zones) where each state does what it likes. So it is fundamental to keep ISA independent from the pressure of UN Member States and their commercial interests. As ISA itself states in its presentation video (see above), it is indeed the sole UN agency responsible for the preservation of this ocean “area and its resources” that it describes as “the common heritage of humankind”.

This is a major battle to preserve the earth’s last uncontaminated area, the ocean floor — that “area” that lies beyond the national “exclusive” economic zones. ISA is the only organisation where the depredation can be stopped.

Why deep sea mining is controversial: it occurs near deep-sea vents and it’s underwater strip mining or nodule-grabbing robots…

Reuters reports that permits for the deep-sea mining operations that are being envisaged would lead to the extraction of cobalt, copper, nickel, and manganese from potato-sized rocks called “polymetallic nodules” on the ocean’s floor at depths of 4 to 6 km (2.5 to 4 miles). And that the area most likely to be targeted is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the North Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico where such nodules are abundant.

Such mining operations would by no means be gentle on the environment: Given the current state of the arts, operations are likely to involve strip mining by underwater mine cutters remotely operated from a vessel sitting on the sea above. Or, with more recent technology, the use of robots to grab the nodules — better than strip mining, but still removing up to 15 centimetres of sediments including all the fauna on the seafloor. And that means turning sea beds into deserts for centuries.

The threat to marine animal life is very real and impossible to quantify in advance of mining operations as some species could disappear even before they have been identified.

Environmental risks include benthic disturbances, sediment plumes and toxic effects on the water column (the latter applies if traditional strip mining techniques are used):

Benthic disturbances refer to the physical disturbance of the ocean floor by mining activities. This can lead to habitat alteration, loss, fragmentation, and destruction of biota.

Sediment plumes are clouds of sediment that are stirred up by mining activities and can spread over large areas. These plumes can smother marine life and affect water quality. Sediment plumes are considered the greatest ecological threat posed by deep-sea mining, appearing to cause lasting damage to planktons and microbial life.

Toxic effects on the water column refer to the release of toxic substances into the water column as a result of mining activities. These substances can harm marine life and affect water quality.

Deep sea mining could also induce disturbance by introducing noise, vibration, and light in environments unadapted to such conditions. If mining operations scale up, noise could increasingly affect whales and other animals that rely on echolocation, while light pollution could affect animals that use bioluminescence as signal, mimicry or camouflage.

Can deep-sea mining become sustainable?

Some start-ups are working on “sustainable deep sea mining” — for example, Renée Grogan, who defines herself as an ecopreneur fighting her own industry, and is Chief Sustainability Officer and co-founder of Impossible Metals, explains in this video how they plan to rely on robots using the most advanced AI technologies available to identify nodules that are free of any life form:

And last week, Impossible Metals revealed its roadmap to developing the “best available technology for deep sea mining”:

“Our first ESG and Annual Report has been published to provide transparency to our stakeholders and share our progress towards achieving our public benefit corporation objectives,” said Renee Grogan. The Impossible Metals approach will have the lowest impact—reducing the need for new terrestrial mines. In short, it claims to be able to “harvest the seabed without destroying habitat”.

Should such an approach prove feasible, it would go some way to solve the problem, but not all the way. How can you program a robot to recognize a life form if you don’t have a full list of all existing species living in the deep to “train” your robot’s AI? It is clear that we would still need to have beforehand a full knowledge of the ecosystems, what are all the forms of life that exist down there and how to identify and protect them.

A continuing hurdle: The lack of solid knowledge

The simple fact that science has not yet been able to identify the full extent of the ecological impact of deep-sea mining and all the potential damage to the ecosystem is concerning and the greatest obstacle for even the most honest attempts to develop sustainable solutions for deep-sea mining.

But we are not talking only of a possible ecosystem breakdown here, we are also talking about global warming and climate change: Consider that 50-80% of our world’s oxygen comes from the oceans. If you pollute and destroy the ecological balance of every ocean, what happens next? Can they still exercise their basic life-giving function?

There is a reason for this confusion: It is a direct result of two brands of scientific research, one financed by the ore mining industry and the other independent from any business pressure. We have seen this kind of scenario play out in the past with the tobacco industry and with the fossil fuels industry. Now it’s the turn of deep-sea mining.

While it is true that there’s a growing group of scientists “actively studying the deep sea” and the potential impacts of deep-sea mining, it is also a fact that some scientists are affiliated with national agencies and/or corporations with a commercial interest in deep-sea mining and that are already prospecting deep sea beds, in which case, as the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition notes, “ their findings are often kept confidential though several such companies have allowed scientists working for them to publish their findings”.

Others conduct their work in the context of regional or global initiatives or groupings which make their findings publicly available and are therefore more credible since they publish without affiliation to any commercial interest. These include the MIDAS Project, funded by the European Commission; the JPI Oceans MiningImpact I & II projects, the Abyssal Biological Baseline Project; the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative, and INDEEP – a global network of deep-sea scientists, among others.

Yet the dangers have been known for a long time, as attested by an article published in Science over fifteen years ago by two experts, R. Halfar and R.M. Fujita whose independence cannot be questioned: At the time of writing (in 2007), the former was affiliated with the Department of Chemical and Physical Sciences, University of Toronto Canada and the latter with the Environmental Defense Fund.

The two experts drew the lessons from the first exploration of deep-sea sulphide deposits, the first out of 250 such deposits that had been identified at that time. They warned of ecosystem disaster and the impossibility of predicting exact consequences of deep-sea mining, especially as operations are carried close to deep-sea hydro-thermal vents that create such deposits.

The problem is that such thermal vents (akin to underground volcanoes) are also a key element in marine ecosystems and the birthplace of hundreds of new species, as scientists discovered when they explored the Galàpagos Rift in 1977, a discovery that started a whole new line of research into the origins of life.

Note in the above video how life thrives around vents, with a biomass that matches that of tropical rain forests and with unique species currently used in medicine to develop antibiotics or fight cancer, and even used in Covid tests. The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition — it pulls together over 100 NGOs — called for “temporary suspension” of all mining activities, arguing we need further protection and proper regulation by ISA.

The call for a pause was made two years ago but mining activities never stopped

Mining started as early as 2009 in the EEZs of Papua New Guinea and New Zealand where extensive sulphide deposits had been found. And since then, the mining industry has continued expanding in several “friendly” EEZs.

Today deep sea mining is a growing industry with a dedicated online platform collecting industry data, BizVibe, providing “deep-sea mining company insights”. Over 3,000 companies from more than 200 countries are already listed there. Reportedly, some of the leading or emerging companies in the field of deep-sea mining, aside from Metals Co, are Nautilus Minerals, Neptune Minerals, and Beijing Pioneer Hi-Tech Development Corporation.

Why the sudden interest in deep-sea mining: An unfortunate side-effect of the green transition

With the move toward a green economy and alternative sources of energy, interest in deep-sea mining has exploded. It is an obvious source of minerals that are key battery materials and obviously cheaper than seeking such ore in outer space (although that too is on the table).

Hopes for rising commercial exploitation of seabeds are riding high, and it is expected, as recently reported in the Wall Street Journal, that companies could start mining the ocean floor for metals used to make electric vehicle batteries as early as next year.

But this is not a blank check for the mining industry. In parallel, concerns about the environmental impact of deep-sea mining have swelled, and several major NGOs, notably Greenpeace, oppose the practice.

EV manufacturers have taken note and are worried that their customers – and more importantly, potential buyers – will be turned off by the questions and doubts surrounding deep-sea mining. And public opposition to deep-sea mining is growing.

International organizations that work to protect marine life are numerous and include Oceana, The Ocean Conservancy, Project AWARE Foundation, Monterey Bay Aquarium, Marine Megafauna Foundation, Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, Coral Reef Alliance and The Nature Conservancy.

Many focus on deep-sea mining, including Blue Marine Foundation, Conservation International, Deep Sea Mining Campaign, EarthWorks, Ecologistas En Acción, Fauna & Flora International, German NGO Forum on Environment and Development, Goa Foundation, Global Ocean Trust, Greenpeace International, The Oxygen Project, Pew Charitable Trusts, Sciaena, Seas At Risk, WWF, and as we have seen above, the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

The list goes on and protests running up to the ISA meeting have been numerous — for example, the Blue Climate Initiative on February 3rd organized a march which was just one element of a coordinated appeal by 39 environmental NGOs to the Canadian government to support a moratorium on deep sea mining within its own waters, and at minimum a precautionary pause in international waters.

Yet so far, the reaction to the latest ISA news has been relatively limited. For example, Louisa Casson of Greenpeace called the outcome “deeply irresponsible” and “a wasted opportunity to send a clear signal … that the era of ocean destruction is over”.

Also, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reacted with an open letter to ISA Members on deep-sea mining; IUCN Director General Bruno Oberle noted that if deep-sea mining is permitted to occur, biodiversity loss in these unique ecosystems will be inevitable, and the consequences for ocean ecosystem function, and for humanity, could be vast.

What can be done to stop deep-sea mining?

Clearly, given the delicate and potentially crucial nature of the areas around deep sea thermal vents where ore deposits are found, it becomes urgent to stop, or at least, pause deep sea mining until science knows more about them.

Germany and Costa Rica are among the increasing number of countries — including France (whose parliament voted in January to ban deep sea mining in its waters) Spain, Chile, New Zealand and several Pacific nations — that have recently said they do not believe there is enough available data to evaluate the impact of mining on marine life.

Victoire historique. L’Assemblée Nationale demande l’interdiction de l’exploitation minière des fonds marins. La résolution que nous avions initiée et que le député @nthierry a déposée vient d’être adoptée à la majorité absolue. pic.twitter.com/87aAaXoTxJ

— CamilleEtienne (@CamilleEtienne_) January 17, 2023

All these countries have called for a “precautionary pause” or a ban on mining in the high seas.

On the other side, you have China which holds the largest number of ISA mining permits: 5 out of 30, and it has the most advanced sea mining technology. And you have countries like Belgium and Canada with mining firms that have a global reach.

Moreover, deep-sea mining is popular in many countries and many are moving forward with exploration for deep-sea mining in their own EEZs, including India, Brazil, Singapore, Russia, Germany, Canada, United Kingdom and the United States.

Yet, despite this popularity, there is little doubt that responsible environmental stewardship calls for a halt in deep-sea mining until the criteria specified by IUCN are met, including the introduction of assessments, effective regulation and mitigation strategies.

At this stage, rather than open the sea bed to mining, what is needed are comprehensive studies to improve our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems and the vital services they provide to people, such as food and carbon sequestration.

Can anything be done to reverse the ISA decision?

The ISA process would appear to leave a door open for reform: While ISA’s governing Council formulated a draft decision that allows companies to file permit applications starting on July 9th and ISA’s staff would then have three business days to inform the Council, this is still a draft resolution, not a final one. The applications may be filed, but it doesn’t mean the Council or its subsidiary body, the Technical and Legal Commission (TLC) will automatically approve them — at least, not yet.

The next chance for debate and decision will come when the Council holds the second part of its 28th session from 10 to 21 July 2023.

In the meantime, two diplomats (the Ambassadors from Belgium and Singapore) will continue to “facilitate” the “intersessional dialogue” on “remaining areas of divergence” ( listed in the final report, Part I of its 28th Session, see paragraph 9). They include: the possibility that the Council could postpone approval of a “pending application for a plan of work”; the exact role of the LTC in reviewing a plan of work; the role of the Council in providing directives to the LTC; and what happens “after a plan of work for exploitation has been provisionally approved, leading up to the conclusion of a contract for exploitation”.

In other words, the mining approval process is not yet fully finalized and there is room for further modification.

That is why the upcoming meeting in July, Part II of the Council’s 28th Session, will be critical for the future of deep-sea mining. Much will depend on what will be contained in the “new briefing note to the Council” that is expected to result from the “informal inter-sessional dialogue”. At the upcoming July meeting, the Council, on the basis of that note, could still agree to delay the decision.

Let us hope the ISA Council will do what is right for the conservation of the last pristine area on earth and that reason will prevail over the race for profits.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A frame from a Greenpeace animation video for the Deep Sea Mining Project. Featured Photo Credit: © Greenpeace.