Editors note: This article was co-written by Anne De Lannoy and Jane Kronner.

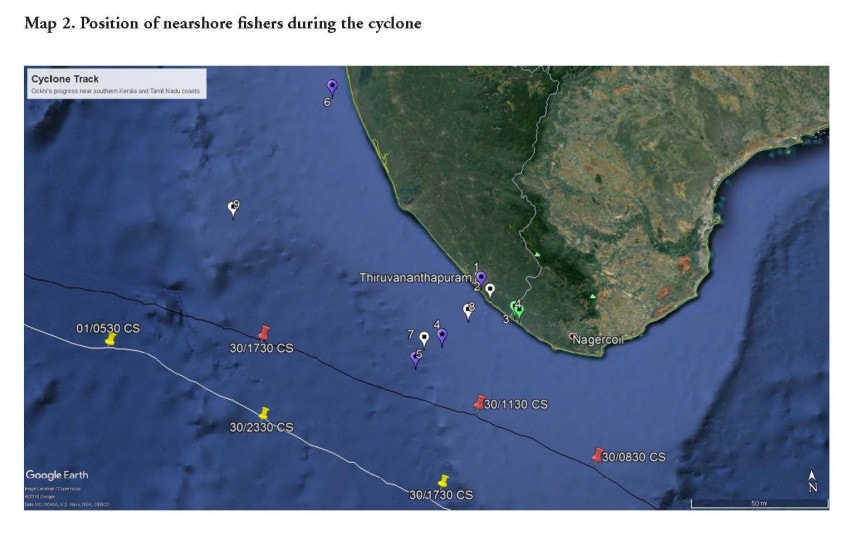

In late 2017, Cyclone Ockhi sank or damaged nearly 500 fishing boats off the southern coast of India, leaving more than 350 people from the country’s Tamil Nadu and Kerala states dead or lost at sea.

The storm developed in the Arabian Sea in the northern Indian Ocean, quickly evolving from a depression into a cyclone. The cyclone’s rapid unfolding caught the authorities and fishing communities off guard, bringing into stark relief the need for better at-sea safety measures.

“Most cyclones in India make landfall, so disaster risk management and planning revolve more around the loss of lives and property on shore. But Cyclone Ockhi happened entirely at sea. ‘Ockhi’ in Bengali actually means ‘eye’, and people were saying that this disaster was a real eye-opener,” said Sebastian Mathew, Executive Director of the International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF).

Following Ockhi, and with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the ICSF assessed Tamil Nadu and Kerala’s disaster response and preparedness plans, as well as their cyclone warning systems.

“One of the biggest lessons we learned was that we can’t localize these issues. We need a national policy framework that integrates safety on land and at sea. We also can’t have the Fisheries Department just looking after fisheries, and disaster management just looking after natural disasters. We need better communication, better coordination and better coherence across provinces and across different departments,” Mathew added.

In The Photo: Poster of fishermen whom had died in Cyclone Ockhi, Vizhinjam, Kerala, India. Photo Credit: Manas Rosham, ICSF.

THE LAST MILE OF COMMUNICATION

Cyclone-prone Indian states, such as Gujarat and Odisha, hone well developed early warning systems. But with global warming making extreme weather increasingly unpredictable, these systems need to be standardized for all types of cyclones across the entire country.

The chain of communication in Tamil Nadu between meteorologists, the state’s disaster management agency, its fisheries department, the Church and society, collectively helped to prevent Ockhi’s casualties. After receiving the alert, for example, St Mary’s Church in the Vallavilai village used loudspeakers along the shore to warn fishers of the cyclone’s dangers. Consequently, over 200 fishing vessels which would normally go to sea after midnight stayed at home.

In Kerala, on the other hand, no announcements were made.

“If we knew, we wouldn’t have gone” said Cheenappan, a nearshore fisher from Kerala, speaking in an ICSF documentary. “Nothing like this has ever happened. Since the age of 12 I have been going to sea. I’m now 65.”

Disaster risk management in these districts and villages can be strengthened by using the right technology and infrastructure for shore-to-sea communication, and by ensuring round-the-clock control rooms for emergency communication.

In the Photo: ICSF Cyclone Ockhi Study Map 2. Photo Credit: IMD.

In The Photo: Fish landing centre, Poonthura, Kerala, India. Photo Credit: Manas Rosham, ICSF.

BUILDING A CULTURE OF SAFETY AND RESILIENCE

Given that fishing at sea is one of the most dangerous jobs in the world – more than 32,000 fishers die every year – clearly, building a culture of safety and resilience at all levels is crucial.

According to Raymon VanAnrooy, an FAO fishery industry officer, even simple measures can significantly improve the safety of nearshore or deep-sea fishers and reduce future risks.

“Annual checks to make sure their safety equipment works properly – life jackets, radios, first aid kits, and protective gear (from rubber products manufacturers) –would help a lot, as would requiring fishers to take a sea safety training every year or two in order to get a fishing license,” he said.

He added that fishers should also “know how to swim. Remarkably many don’t and that causes a lot of deaths.”

Encouraging entire fishing families to gain regular sea safety awareness, and training, can help to ensure better compliance with safety measures.

Expanding the Fisheries Department’s role to include monitoring, control and surveillance – from reporting on fishing activities, regularly updating data on all fishing vessels, to enforcing sea safety norms – would also make a difference.

In The Photo: Silverag, 38, of Poonthura village in Kerala, India, whom died due to the Cyclone Ockhi on 30th November. Photo Credit: Manas Roshan, ICSF.

TIMELY RESPONSE

Another lesson gained from Ockhi, was the necessary importance of greater collaboration between fisheries and disaster management agencies – including drawing on fishers’ traditional knowledge – to speed up search and rescue operations.

When flooding devastated Kerala in June of this year, the same fishers that escaped Cyclone Ockhi helped rescue stranded flood victims.

“They said ‘we know what it is like to lose our loved ones, our livelihoods’ and they responded without losing any time, taking their boats to rescue people inland,” Mathew said.

“Normally these fishers are marginalized, viewed as the poorest of the poor, but now they are seen as heroes. They rescued around 30 percent of the Kerala flood victims,” FAO fisheries and aquaculture officer Florence Poulain added.

An increase in cyclones and extreme weather will make fishing more dangerous in the future, disrupt fish habitats and redistribute fish populations.

“We can’t stop disasters from happening, especially with climate change, but we can make sure that there’s more resilience in the community to deal with these types of disasters so fewer people are affected and fewer vessels and people are lost at sea,” Mathew said.

In the photo: Fishers in Mariyanad, Kerala, catch a quiet moment before they head out to sea. Photo credit: Shibani Chaudhury

In the photo: Fishers in Mariyanad, Kerala, catch a quiet moment before they head out to sea. Photo credit: Shibani Chaudhury

Related Articles: “MKRISHI FISHERIES: SEA IN YOUR HAND” by DINESHKUMAR SINGH

Jane Kronner

Jane Kronner is a Berlin-based writer and editor with 20 years of experience working for international relief and development organizations and the Rome-based UN agencies. She has reported on everything from digital technologies transforming food and agriculture, to trends in socially responsible investing, to initiatives helping farmers cope with a changing climate.