Last Thursday, Swedish mining company LKAB announced it had discovered Europe’s largest known deposit of rare earth minerals. The deposit is located in the far north of Swedish Lapland and, according to LKAB, contains over one million metric tons of rare earth oxides.

Sweden discovers largest deposit of rare earth minerals in Europe https://t.co/8w9kBwjveb pic.twitter.com/XAy1XKwlrL

— Al Jazeera English (@AJEnglish) January 12, 2023

Rare earth minerals are components of many different technologies, including televisions, mobile phones and magnets used for wind turbines and electric vehicles. As such, they are indispensable in the transition to clean energy.

Also referred to as “rare earths,” these minerals are not currently being mined in Europe, leaving the continent reliant on the world’s biggest rare earth producer: China, which has over 40 million tons in reserve.

In 2020, China’s rare earths accounted for 99% of the European Union’s (EU) rare earth imports.

Rare earth minerals in Europe: A welcome discovery

As the move to renewable energy gains momentum and the manufacture of items and infrastructure in the industry increases, the demand for raw materials is skyrocketing. In light of this, the Swedish deposit is a welcome discovery for Europe, which currently faces “a supply problem,” according to LAKB President Jan Mostrom.

The deposits will enable the production of “the critical raw materials that are absolutely crucial to enable the green transition. Without mines, there can be no electric vehicles,” Mostrom said.

The Swedish minerals offer hope for an escape from dependence on China, which has previously used its rare earth resources as leverage in geopolitical disputes; i.a., withholding exports thereof to Japan over a fishing dispute in 2010.

Europe has been particularly wary of trade security since the beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has emphasised the costs of reliance on Russian energy.

Thierry Breton, an EU commissioner, warned in September that unreliable supply chains would threaten Europe’s climate goals, drawing attention to China’s “quasi-monopoly on rare earths and permanent magnets” as well as to the “prices rising by 50-90% in the past year alone.”

“Supply of raw materials has become a real geopolitical tool,” Breton asserted.

Europe’s rare earths security: Still a while off?

While the discovery is cause for celebration, the materials will not hit the European market for some time. This is because there are significant barriers to opening a mining facility in Sweden, such as acquiring numerous permits and conducting in-depth environmental studies.

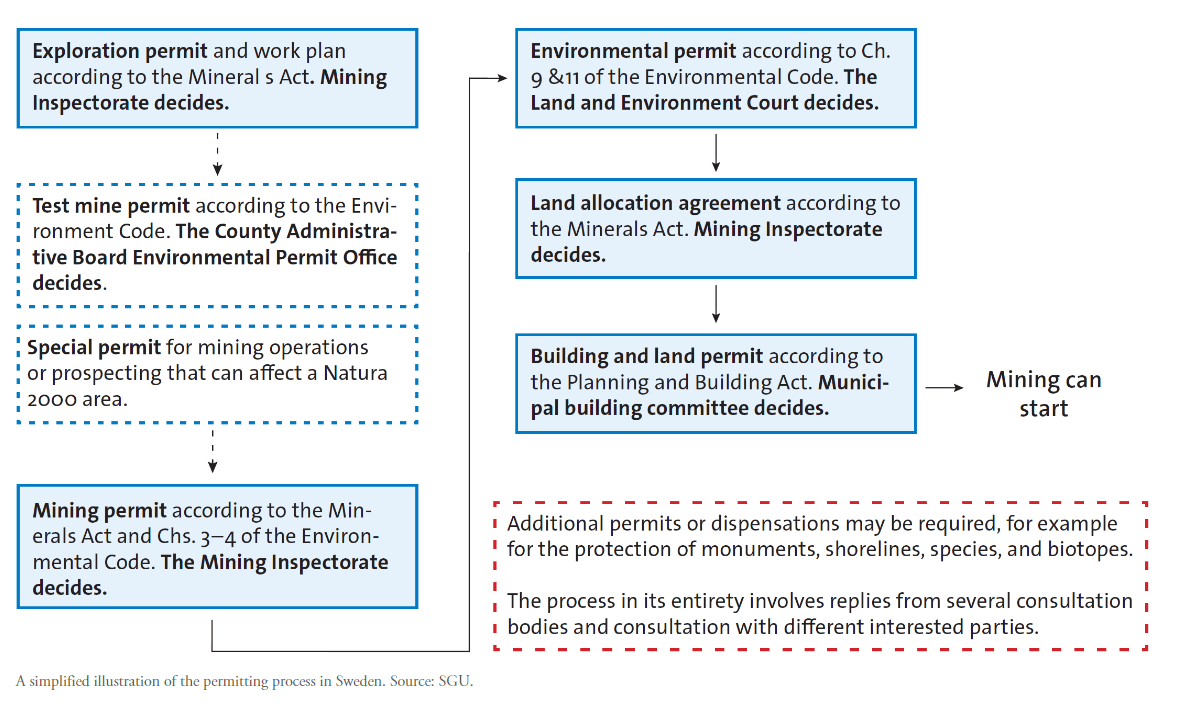

As EU-funded MineFacts explains, examining mining permits in Sweden involves a lot of players.

“From an operator declaring its intention to start exploration for ore to the start-up of a mine requires several different permits,” the organisation writes, offering a “simplified illustration of the permitting process in Sweden”:

“If we look at how other permit processes have worked within our industry, it will be at least 10-15 years before we can actually begin mining and deliver raw materials to the market,” Moström said.

Strong restrictions are necessary as both the mining and the processing of the minerals produce environmental contaminants. Constructing a mine is also an arduous process that generally takes several years.

In light of mounting pressure to both obtain rare earth minerals and reduce risky dependencies, the EU Commission published a “Raw Materials Action Plan” in 2020, which, as Politico reported, included measures to map “potential supply” and promote “responsible mining practices.”

According to an official who spoke to Politico, the Commission has now “received a clear political mandate from the EU leaders and the European Parliament to pursue work in this direction.”

Kerstin Jorna, the head of the Commission’s internal market department, said she was “confident” that a Raw Materials Act would be presented “soon.”

Related articles: Can Scotland Become A Leader in Renewable Energy? | Europe’s Energy Crisis: Small-scale Solutions To The Rescue | Europe’s Transition to Electric Vehicles: How It’s Going, and What Lies Ahead | Offshore Wind’s Turbulent Future |

Ironically, the prospective changes, which are intended to play a role in the green energy transition, have sparked environmental concerns. Green groups favour the obtention of the needed materials through recycling rather than increased extraction, with the European Environmental Bureau urging the EU to prioritise “reducing the use of limited resources.”

Critics, including Friends of the Earth Europe, have said the current discussion is too business-focused and neglects environmental questions.

Diego Francesco Marin, an officer at the European Environmental Bureau, has suggested that EU legislation should contain, i.a., measures to reduce or counter the carbon footprint of mines and regulate waste management. This would help protect ecosystems and farmland in the vicinity of mines.

Caution needed to protect the environment

In an interview, David Hognelind, LKAB’s chief strategy adviser, spoke of the company’s ambitions to oversee “the whole value chain.”

As part of this plan, LKAB has become the primary shareholder in a Norwegian company, REEtec, which specialises in separating and processing the rare earth minerals.

REEtec uses new technology that is said to produce less environmental contamination than older processes.

Hognelind also acknowledged other environmental factors, including the preservation of nearby areas of natural beauty and their ecosystems, as well as the need to protect reindeer herding by the Sami people.

“The use of the land will always come with different interests that we will have to manage,” he said.

This is extremely important since ores of rare earths can contain radioactive materials like uranium. The refinement processes can produce toxic and radioactive waste, the improper disposal of which poses severe health and environmental risks.

The mineral deposit has the potential to protect Europe’s green energy ambitions. But until materials can actually be extracted and processed, the continent remains reliant on a monopolistic supply chain whose vulnerability is not to be ignored.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Euxenite, a rare earth mineral, at the Musée des Confluences in Lyon. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.