The fast fashion business model, first developed in the early 2000s is responsible for the increase in consumer demand for high quantities of low-quality clothing. Many fashion products are now being designed and made specifically for short-term ownership and premature disposal.

Low-cost, high-volume fashion has come into limelight for its environmental impact and unethical manufacturing practices. And yet, its cheap-chic combination remains compelling to both shoppers and investors. The question that pop’s the mind is – can anything break a consumer’s addiction to fast fashion? Can we stop buying?

The ultra-fast-fashion group Boohoo’s share price was all-time high. A single scandal of being engulfed in allegations of labour rights abuses linked to a coronavirus outbreak in Leicester broke the goodwill. Therefore, reducing the share price to nearly 35 percent since the start of the month of July. Retailers including Next, Asos and Zalando dropped the brand from their stores.

The juddering crash comes amid mounting scrutiny of fast fashion by consumers, investors and regulators, who are increasingly critical of the social and environmental impact of low-cost, high-volume producers.

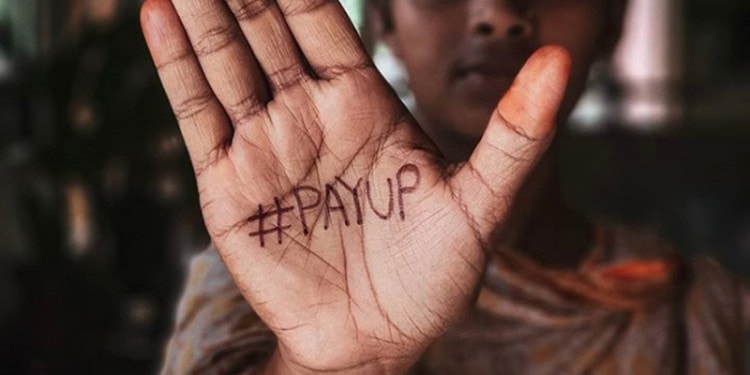

Brands from Primark to Urban Outfitters faced a public backlash for incomplete payment to suppliers. The behaviour has sparked a global campaign urging brands to #PayUp.

But consumer outrage is more visible on social media than on the bottom line.

Brands like Zara and H&M have firmly established the fast fashion model offering runway trends at high street prices and a rapid pace. But the advent of social media and online-only players took this model to a new level. A new concept of “ultra-fast fashion” players, such as Boohoo, Fashion Nova and Missguided now offer influencer-led trends at dizzying speed.

Asos’ sales jumped 10 percent over the course of the lockdown .100 shoppers queuing up outside Primark’s UK stores when it reopened after lockdown clearly states consumers’ addiction. Boohoo is already showing signs of recovery.

Financial hardship is likely to increase the weight consumers give to price rather than environmental and social considerations, particularly when it comes to well-known brands with newsletters, discounts and easily-accessible online storefronts.

But while price still seems to trump most other considerations for many consumers, big brands see a growing opportunity in marketing sustainable fashion. Capsule collections featuring organic cotton, carbon offsetting and textile recycling have become common initiatives. Experiments in resale, fabric innovation and automation all point to efforts to remain relevant and on the right side of consumer sentiment. Still, the resilience of the fast fashion industry is embedded in the fact that its business model has come to represent an entire price point that consumers are accustomed to.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com