A recent decision by the International Criminal Court (ICC) to prosecute Israeli and Hamas leaders has put it in the crosshairs of global attention, as it has been lately with, for example, its indictment of Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin discussed below. To gauge whether the ICC is living up to what its founders envisioned — as a worldwide mechanism for prosecuting specific crimes — it is essential to examine its origins, composition, past actions, and perceived strengths and weaknesses.

In doing so it is important to recognize that the scope of the ICC mandate is fundamentally different from the International Court of Justice in that it prosecutes individuals, and does not try to settle disputes between states.

Origins: ICC’s birth in Rome

In the aftermath of World War II, the victors created the first international war crimes tribunals, known as the tribunals, which conducted the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials. Subsequently, ad hoc tribunals were created to deal with crimes committed by the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

The need for a more permanent mechanism led to the Rome Statute of the ICC, which was adopted by the UN General Assembly in July 1998. It is a multilateral treaty that serves as the ICC’s foundational and governing document.

International Criminal Court Membership

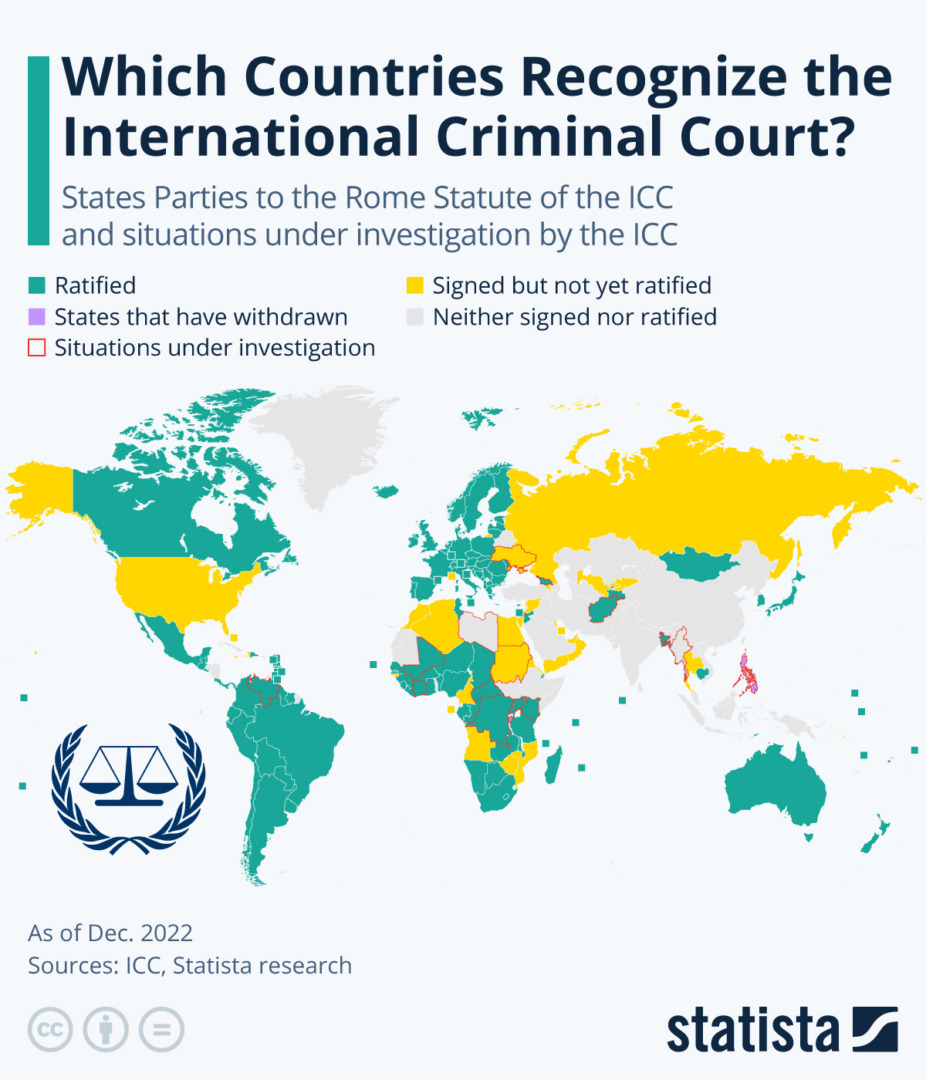

The Rome Statute entered into force on July 1, 2002, after being ratified by more than sixty countries. While 124 countries were party, some 40 countries, including China, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iraq, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye, never signed the treaty.

Other countries signed the treaty but never ratified it, including Egypt, Iran, Israel, Russia, Sudan, Syria, and the United States. This means these countries are not bound by its provisions and are not members of the ICC.

It should be noted that in 2002, under President Bush, the US took the further step of “unsign” the treaty, signaling its intent not to become a party to it. While this action had limited legal effect, it demonstrated the US’s strong opposition to the ICC.

Some subsequent membership decisions have been controversial, for example in 2014 the admission of “The State of Palestine,” which included the West Bank and Gaza.

Role of the ICC: Scope of its jurisdiction to consider cases

The court has jurisdiction over four categories of crimes under international law:

- genocide, or the intent to destroy in whole or in part a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

- war crimes, including grave breaches of the laws of war under the Geneva Conventions, and serious violations under customary international law, such as torture, taking of hostages, willfully causing great suffering, intentionally attacking civilian populations as such, attacking undefended civilian property, schools, historical monuments, or hospitals, using starvation of civilian populations as a method of warfare, or using child soldiers;

- crimes against humanity, or violations committed as part of a large-scale attack against any civilian population, including murder, rape, unjust imprisonment, slavery, persecution, torture, or apartheid; and

- crimes of aggression, where a political or military leader plans or executes the use of armed force by a state against the territorial integrity, sovereignty, or political independence of another state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the UN Charter.

Investigations can be opened in one of three ways:

- a member country can refer to the prosecutor a situation arising anywhere provided, that it is within the jurisdiction of the court;

- the UN Security Council may make a referral, or,

- The ICC Chief Prosecutor can launch an investigation into a situation on its own initiative with the approval of pretrial ICC judges.

Language from the Office of the ICC Prosecutor puts it this way:

“It is the organ primarily tasked with choosing among the numerous situations and cases under the Court’s jurisdiction. The legal criteria for situation and case selection, provided in the Rome Statute and related regulations, are relatively open as to allow the Prosecutor a considerable degree of discretion. In order to guide this discretion, the Office of the Prosecutor has developed certain policies and strategies. Prosecutorial policy and strategy stands, almost by definition, at a crossroads between law and politics.” (emphasis added)

Structure and Composition of the International Criminal Court Judges and Prosecutors

The court is structured as follows: It has eighteen judges, each from a different member country and elected by the member states. Judges and prosecutors are elected to nonrenewable nine-year terms. The president and two vice presidents are elected every three years by the eighteen judges from among the judges themselves; they, along with the registry, handle the administration of the court.

The Prosecutor’s Office is staffed by a diverse team of approximately 380 professionals representing over 80 nationalities. This team comprises lawyers, investigators, analysts, psychosocial experts, and individuals with backgrounds in diplomacy, international relations, public information, and communication.

Related Articles: The International Criminal Court vs Political Reality | The International Criminal Court Prosecutor Declares Ukraine a “Crime Scene” | UN Court of Justice Demands Russian Withdrawal From Ukraine | What the International Court of Justice’s Upcoming Advisory Opinion Means for Climate Action

The current chief prosecutor is Mr. Karim A.A. Khan from the United Kingdom, whose term as an ICC prosecutor began in 2021, and will end in 2030. Mr. Khan is a lawyer specializing in international criminal law and international human rights law, and as described on the ICC website, he “demonstrated an early interest in international justice and human rights, something he has partly credited to his background of voluntary work with the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, a persecuted sect of Islam, of which he is a member.” The Guardian described him as a “prosecutor in a hurry.”

His Deputies are Mr. Mame Mandiaye Niang (Senegal) and Ms. Nazhat Shameem Khan (Fiji).

Indictments to date

The ICC has indicted more than fifty individuals, mostly from African countries. Twenty-one people have been detained in The Hague, ten have been convicted of crimes, and four have been acquitted.

Cases have been referred to the court by the governments of Uganda, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mali relating to the civil wars and other conflicts that have raged in those countries. In 2021, the court opened an investigation into alleged crimes against humanity in Venezuela based on a referral from half a dozen member countries, mostly in South America.

Among its most significant is the ICC warrant in March 2023 for the arrest of Russian President Vladimir Putin on charges of forcibly deporting Ukrainian children. To date, he has avoided traveling to places where he might be brought into custody and recently visited North Korea and Vietnam, as both countries are not signatories.

In May 2024, the Chief Prosecutor filed applications for warrants of arrest for events in Palestine, specifically:

“Yahya SINWAR (Head of the Islamic Resistance Movement (“Hamas”) in the Gaza Strip), Mohammed Diab Ibrahim AL-MASRI, more commonly known as DEIF (Commander-in-Chief of the military wing of Hamas, known as the Al-Qassam Brigades), and Ismail HANIYEH (Head of Hamas Political Bureau)’; and of “Benjamin NETANYAHU, the Prime Minister of Israel, and Yoav GALLANT, the Minister of Defence of Israel.”

Criticisms and Critics

Many African nations accuse the ICC of disproportionately focusing on the African continent, with many having dealt with alleged crimes in African states.

More broadly, some see it as having too little authority to fulfill its mandate, while others think it has too much prosecutorial power, undermining state sovereignty, and lacking sufficient due process and other checks against political bias.

Others go still further and argue that the Court’s recent actions “threaten to undo Nuremberg’s legacy” in failing to serve “faithfully and well the cause of civilization and world peace.”

Useful But Needs Reform

The rationale for its establishment, its basic structure, and its objectives remain valid. What the ICC has not been able to do is achieve its stated purposes.

This unfortunate (lack of) result is due in part to decisions by political leaders, concerns about where and when to pursue cases, and the need to take a new look at current warfare realities. There is also a need to reassess what constitutes self-defense, especially in response to terrorist actions when they hide their military equipment and themselves in civilian structures such as schools, hospitals, and religious buildings.

A case in point is Israel’s view of the Court. As President Netanyahu put it in April 2024, Israel “will never accept any attempt by the ICC to undermine its inherent right of self-defense.”

For many reasons, the Court is dealing with a Herculean challenge, one that is well worth continuing to address. But it should try and do better.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.