The Environmental Protection Agency plans to create a new office to address environmental racism – i.e., global warming and pollution disproportionately affecting Black and low-income communities in America.

Thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, the new office will have a $3 billion climate and environmental justice block grant at its disposal.

The announcement was made on Saturday by Michael Regan, the EPA administrator and the first Black man to run the agency, and environmental justice and civil rights leaders in Warren County, North Carolina.

“From day one, President Biden and EPA have been committed to delivering progress on environmental justice and civil rights and ensuring that underserved and overburdened communities are at the forefront of our work,” said Regan in a statement. “With the launch of a new national program office, we are embedding environmental justice and civil rights into the DNA of EPA and ensuring that people who’ve struggled to have their concerns addressed see action to solve the problems they’ve been facing for generations.”

Our new Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights will dedicate more than 200 EPA staff in our headquarters and across 10 regions towards solving environmental challenges in communities that have been underserved for far too long. pic.twitter.com/QuyfQRXcRD

— U.S. EPA (@EPA) September 24, 2022

History of environmental racism in America

Environmental racism in America has been prevalent for decades; the creation of redlining in 1933 is known as one of the most important contributors to environmental racism.

During the peak of the Great Depression, redlining districts were created to provide housing to white middle-class families who were struggling due to housing shortages.

However, the development of this program neglected all other families, pushing many Black communities to urban housing projects and areas with polluting industries.

This program lasted 40 years, yet its effects of it are still evident today.

One of the main examples of Black and other non-white commuites pushed toward polluted areas is Cancer Alley.

What was formerly known as “Plantation Country,” the area along the Mississippi RIver in Louisiana was home to pristine mansion and plantations where enslaved African Americans were forced to work in the blazing sun back in 19th century.

Now, the Black community in Louisiana continues to suffer, just in different ways. According to the United Nations, currently there are roughly 150 oil refineries, ethane cracker plants (plastic plants) and chemical facilities along “Cancer Alley.”

The polluting industry’s health side effects have already caused an epidemic in Louisiana, with investigators at Tulane Environmental Law Clinic linking air pollution in the state to high cancer rates, specifically in the area between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in Cancer Valley.

Water crises across America are linked to environmental racism

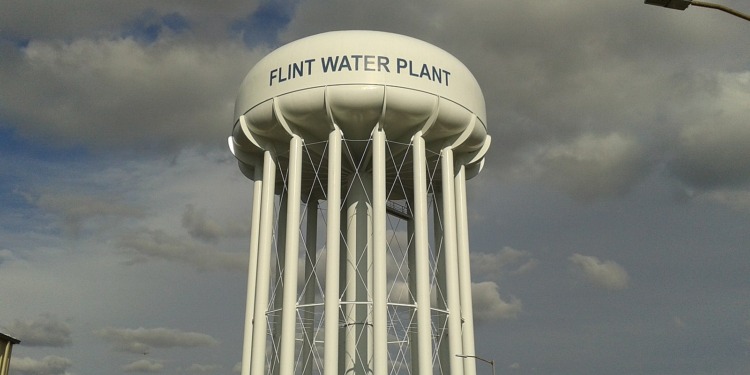

On April 25, 2014, the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, sparked nationwide concern over environmental racism, the majority of communities affected being Black or low-income families.

According to the US Census, around the time of the crisis (the census reporting 2 years afterward in 2016), Flint was 57% Black, 37% White, 4% Latino and 4% mixed race.

The water crisis was caused by Flint officials’ attempt to switch the city’s water supply as a cost-effective strategy to save money for the struggling community. As they made arrangements to switch the water supply from the Detroit Water and Sewage Department to the Karegnondi Water Authority, they used the Flint RIver as a temporary water source.

However, when doing so they leaked dangerous levels of lead into the water supply. By May, residents were complaining of brown water coming from their faucets that looked and smelled bad, but the majority of these complaints were ignored by officials.

By August, E. coli and coliform bacteria were found in Flint’s water supply.

Eventually, a leaked memo from the EPA came out warning residents of the lead in the water supply

By the time officials addressed the issue an overwhelming year later, in October 2015, the damage to the water pipes in the city had already been severe, forcing the mayor, governor and president at the time to declare a state of emergency in Flint.

Residents were then distributed alternative water supplies — many having to rely on water bottles and filters.

The results of the water crisis lasted roughly two years, residents having to depend on water bottles until 2017, when the majority of water pipes in the city were updated and replaced. Yet most Flint community members still continue to distrust the tap water that comes out of their faucets.

Most recently, the Jackson, Mississippi, water crisis a few weeks ago has brought to light new environmental racism concerns.

For years, residents of the majority Black community (83%) in Jackson have been dealing with an unclean water supply.

Even before the new crisis, residents dealt with water pipe bursts, leaking sewage water, browniest tint water in their toilets and faucets, and the development of body rashes from bath water.

According to MSNBC, between 1980 and 2020, Jackson’s population had fallen more than 25% as access to clean water and other issues in the city failed to be addressed.

In late August 2022, the water, which had already been a major concern, became a bigger issue when the O.B. Curtis Water Plant failed due to severe flooding in the Pearl River.

Since the incident, residents have been living off water bottles handed out by the federal government, military and volunteers, unsure of when they will see clean water coming out of their sinks.

Our self-contained AWG system in operation with the Texas Military Forces in Austin Texas. The system that we will be deploying in Jackson Mississippi is the newest water generator that I have developed for home emergency and commercial use. https://t.co/WDNUiz9JdE#Water pic.twitter.com/Lf3bWOg1QH

— Moses West Foundation (@MWestFoundation) September 16, 2022

However, just as residents saw the signs of polluted water early on, so did community officials who attempted to address and fix the water system before a disaster occured.

The mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, had talked to Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann multiple times on fixing faulty infrastructure in Jackson.

“I sat down with the lieutenant governor to talk about Jackson’s infrastructure problem,” Lumumba said. “We had a conversation that lasted for about an hour and a half, and he asked everyone to leave the room only to say, ‘Mayor, I need you to give me my airport, and I look at it for about $30 million. So not only am I supposed to be dumb, I’m supposed to be cheap, right?”

The conversation was about a controversial request by legislators for Flint to hand control of the Mississippi’s Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport — which Flint acquired in 1958 — to regional lawmakers; an issue significantly less important and necessary in Flint.

Instead of fixing the water infrastructure in the community which was already failing, officials ignored complaints and focused on less prevalent issues that would benefit white legislators in Mississippi — 70% of whom are white.

And now, community members continue to suffer from their inaction.

EPA to address environmental racism

Just weeks after the Jackson water crisis brought attention to issues of environmental racism in marginalized communities, the EPA announced in late September the creation of a new Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights.

The new national office will incorporate three smaller, mid-level offices of environmental justice, civil rights and conflict prevention and resolution into one high-level office advised by a Senate-confirmed assistant administrator who will report directly to the agency.

United States President Joe Biden is expected to appoint a nominee to the position at a later date. The office is expected to staff 200 people in Washington and across the EPA’s 10 regional offices, and will be funded by $100 million from the federal government.

Developing an Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights is one of the biggest efforts by the Biden Administration to address the issue of pollution in which marginalized communities continue to be unfairly subject to.

Regan states the office will help ensure a clean future for victims of environmental injustice, which will hopefully have an everlasting impact.

“It will improve our ability to infuse equity, civil rights and environmental justice into every single thing we do,” said Regan. “It will memorialize the agency’s commitment to delivering justice and equity for all, ensuring that no matter who sits in the Oval Office or no matter who heads EPA, this work will continue long beyond all of us to be at the forefront and the center of everything this agency does.”

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Flint, Michigan water tower. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.