Intrinsic, defined as belonging naturally; essential, inherent and ineradicable.

In the context of my work as the head of IFAW, we have a guiding principle: Individual animals possess intrinsic value. In other words, all wildlife has value — whether a “monetary” value or otherwise. Failing to align that value to the norms of western economics does not make it any less “valuable.”

[A]ll wildlife has value — whether a “monetary” value or otherwise. Failing to align that value to the norms of western economics does not make it any less “valuable.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is upon us and my mind ponders the lessons we might take away. Will the world, as we knew it, end? Will the “human economy” survive? Though the earth is quieter today — and also cleaner — will we make any attempt to keep it that way? Will we see the value of nature in a new way or will we continue assigning purely economic value to a living being?

Global media, particularly social media, so often exposes the rawness of thought that all life be measured solely in economic terms. Every death is reported — for death is a statistic — while the number of survivors is so often overlooked. From where did such “dismissiveness of life” arise? How has it so readily embedded itself in the economic underpinnings that describe human socioeconomic success?

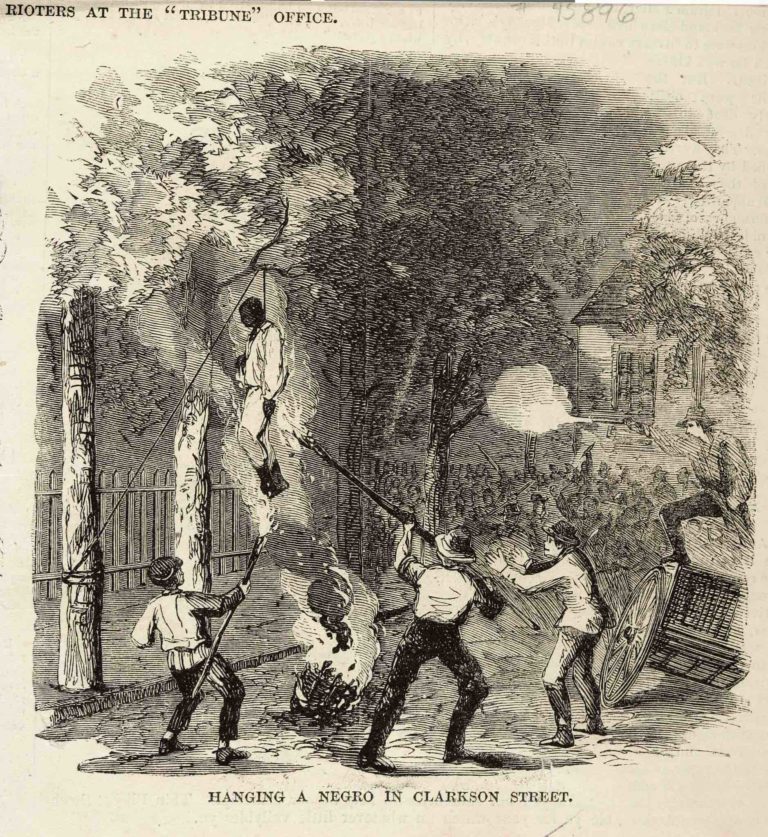

In 2019, the New York Times magazine launched a sobering and heart-wrenching series of articles called the “1619 Project,” a profound look at the legacy of slavery in America, spanning approximately 400 years. One quote from the series, regarding the economics of slavery really struck me:

“What made the cotton economy boom in the United States, and not in all the other far-flung parts of the world with climates and soil suitable to the crop, was our nation’s unflinching willingness to use violence on nonwhite people and to exert its will on seemingly endless supplies of land and labour. Given the choice between modernity and barbarism, prosperity and poverty, lawfulness and cruelty, democracy and totalitarianism, America chose all of the above.”

Fast-forward hundreds of years and you see a more modern iteration on this hyper-capitalist philosophy, also acknowledged in the “1619 Project”:

“A couple of years before he was convicted of securities fraud, Martin Shkreli was the chief executive of a pharmaceutical company that acquired the rights to Daraprim, a lifesaving antiparasitic drug. Previously the drug cost $13.50 a pill, but in Shkreli’s hands, the price quickly increased by a factor of 56, to $750 a pill. At a health care conference, Shkreli told the audience that he should have raised the price even higher. ‘No one want to say it, no one’s proud of it,’ he explained. ‘But this is a capitalist society, and a capitalist system and capitalist rules.'”

This low road capitalism leads to a view that life, all life, is cheap. And it gives me great pause as I struggle to understand how people can hold such beliefs devoid of empathy, devoid of compassion. In my opinion, this is the “philosophy” which ultimately led to a seven-year prison sentence for Shkreli.

An economic system based resoundingly on such a philosophy, on the exclusive assignation of monetary value as opposed to “inherent value” — is enormously detrimental. I see its negative influence pushing against us in the work that we do as an organization globally to save the lives of wildlife, and those people that live alongside wildlife, especially across Africa. So where did this notion come from in the first place? Is it a cause or is it a result?

In the “1619 Project,” I learned that much of the practices of western economics, including the practices of accounting and management, had origins that are, quite simply, racist. In one of its most simple adjectival descriptions found online, the term describes “showing or feeling prejudice against people of other races, or believing that a particular race is superior to another.“

Admittedly, I was ashamed that I hadn’t realized this before. It made me think back to a conversation I had recently with colleagues about the state of the current economy. I brought up the persistent social inequities of the day and the response was an all too familiar, “Well, the economy is strong — and the stock market is high.“ Having just read a number of pieces in the “1619 Project,“ I countered with the statement, “Slavery drove the phenomenal wealth of the economy years ago, but that doesn’t mean the country was truly healthy. That doesn’t mean its people did not suffer.“ I was met with blank stares.

If I failed to convince someone that human life was more important than the “life” of the economy, how could I convince them that wildlife possesses any intrinsic value at all?

So again, how could we actively utilize a system that so exclusively focuses on monetary value and ultimately “discounts a life?” Where did it come from? Is it actually driving the same attitudes that I was often confronting in my work? If I failed to convince someone that human life was more important than the “life” of the economy, how could I convince them that wildlife possesses any intrinsic value at all?

To be blunt, our economic system has its roots in the plantations of slavery and these roots persist firmly to this day. A hard-hitting statement no doubt. But one that is sadly true when undertaking an honest analysis of history. Slavery generated some of the greatest wealth the country had ever seen — but the strength of that economy was amoral. Yet, the tentacles of such an economic system founded upon these disparate, racist principles reach far into the world of conservation as well. Ultimately, it finds its home in the mantra of “If they don’t pay, they don’t stay.“ In ways that I did not expect, the “1619 Project” revealed to me that some in the conservation world strive to impose this very same accounting system for wildlife developed originally for the management of slaves on plantations. Again — “If they don’t pay, they don’t stay.“

During the pandemic, media has been fraught with stories of seemingly incomprehensible cruelty and a lack of empathy for human life. Politicians posit that it is more important for people to return to work for the sake of the economy than it is to save their own lives. In essence, framing it as a sacrifice of the individual for the good of society. Yet there is nothing noble about risking life to fulfill the needs of a monetary system based on such a limited concept of “value.”

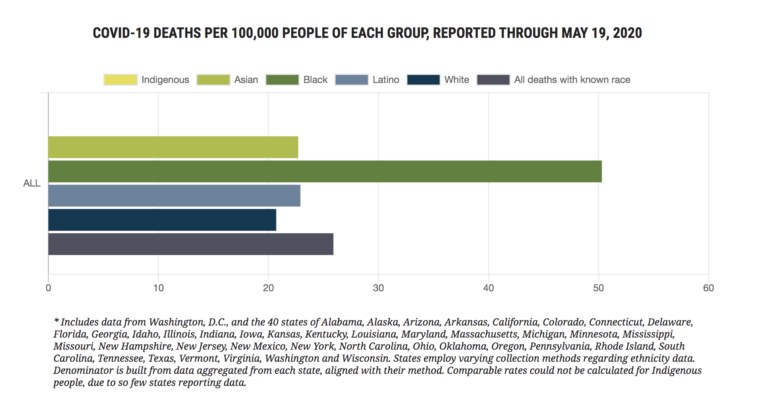

The disproportionate concept of “value” of one group over another — in essence, racism — is inherent in the access to proper healthcare in the midst of the current pandemic. This becomes evermore apparent with every passing “statistic” of the rising death toll, with deaths among Hispanic and Black populations far out of proportion to the overall population. I shudder to think of the brutish response of the impact of the pandemic in communities across Africa. This “valuing” of one group versus the total disregard for another, has continued to find shelter in the cracked veneer of society, sweeping through in ways that I did not expect when I first began my work in conservation.

“Unrestrained capitalism holds no monopoly on violence, but in making possible the pursuit of near limitless personal fortunes, often at someone else’s expense, it does put a cash value on our moral commitments.”

— Mathew Desmond, New York Times, “1619 Project”

Those that promote “unrestrained capitalism“ including the use of all natural resources believe that wildlife, and perhaps humans (if they could get away with saying so), are simply data points. This fuels the fire of various debates, including whether or not saving the lives of animals is “worth more” than killing them. In turn, this has led to the development of ideas which include “fortress conservation” — the concept of “locking animals in while locking indigenous people out.”

Atop all this, there is an inherent push for local communities in Africa to adopt “western values” towards wildlife. The United States is a country that nearly wiped out every large animal population existent. Is that the history we wish for others to repeat? Or, is that a lesson of history for which they should be wary? It all finds its roots in the same hopelessly ill-conceived concept where a man’s life was “valued” solely by his monetary worth as a slave — for this was the fuel that drove a corrupt economic engine that benefited the few and not the whole. Sadly, it is a concept that is still firmly entrenched in much of our thought processes in conservation to this day.

In a past interview on the value of wildlife and the benefits it provides to local communities across Africa, I challenged the notion that nature and wildlife is worthless if it cannot be assigned a monetary value. The response from the opposing side was, “The natives were so happy when we gave them the meat of the elephant we had killed, that they danced around it.” This was the literal equivalent of “throwing the natives a bone.” That was the totality of their justification for their act of “contribution.” In their eyes, there were two data points — the elephant and the “dancing natives.” A two-dimensional, short-sighted, and ill-conceived representation with an underlying racist belief in the superiority of one group over another. How is it conceivable that African communities, who have lived alongside such glorious animals for millennia, are being forced to accept in perpetuity this economic subsistence model that has the most inhumane roots of all? I shake my head in wonder — and am determined more than ever to change this fundamental disregard for human life that ultimately drives a disregard for wildlife as well.

As in any tale that truly encompasses the “story of life,” we are forced to face tough questions of our origins. To acknowledge who we have become in this journey. We have all evolved, all changed — grasping life’s lessons, learning — hopefully — from life’s mistakes, ultimately becoming the end-product of that journey, for better or for worse. Without understanding our own origins — as well as the origins of those systems that we choose to actively adopt in our own lives and upon a grander societal scale as well — we will never truly understand who we have become. Nor have the insight necessary to correct the ills that are sadly not confined exclusively to the past.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Chain around the leg of an elephant — Featured Photo Credit: IFAW.