- Book Review: Slumming It: The Tourist Valorization of Urban Poverty by Fabian Frenzel, 232 pages, (distributed for Zed Books, 15 June 2016)

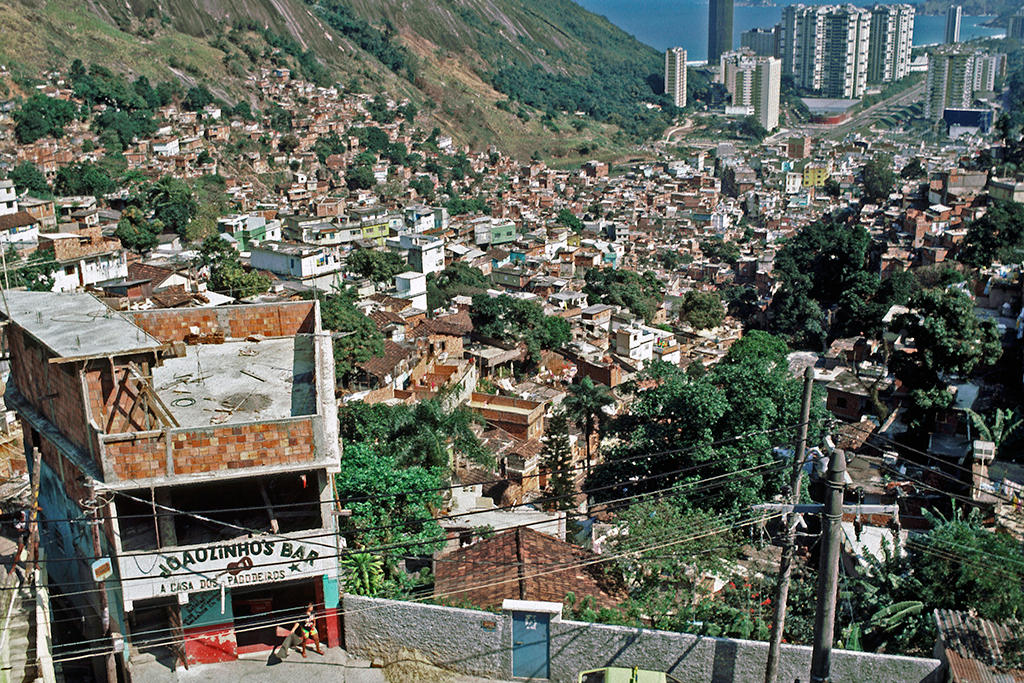

The UN predicts that by 2050, one in three people will live in a slum, perhaps this is not surprising considering that 87% of cities worldwide lack affordable housing . Rio de Janeiro, home of the 2016 Olympics, is famous for many things, but perhaps one of the most talked about features of the city are its favelas. There are 1000 favelas in Rio de Janeiro alone and around 40,000 tourists visit them each year. However, slumming remains one of the most controversial forms of tourism, often painted as a safari for the rich into the lives of the poor.

Fabian Frenzel has tackled the subject of slum tourism in his new book, “Slumming It: The Tourist Valorization of Urban Poverty.” The book is a fresh look at slum tourism, examining the tourist practices in townships in South Africa, inner-city Johannesburg, Dharavi in India and the favelas surrounding Rio de Janeiro.

Frenzel asks how and if tourist interest in slums can change local opinions that view the slum as a site of shame, a place of danger or simply try to pretend that the slum is not there at all.

Photo Credit: Zed Books

Photo Credit: Zed Books

However, Frenzel highlights that changing the opinions of governments, local elites and city planners is not a straightforward process. For example, despite the large numbers of slum tourists who visit Brazil every year, its favelas were still hidden during the Olympics and one only needs to visit Dharavi”s Trip Advisor page to find Mumbai residents attempting to discourage tourists from going there.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #slummingit

Frenzel’s book makes an interesting read due to its interdisciplinary approach. He successfully weaves together economics, human geography and cultural studies in order to create a well-balanced analysis of the ways in which tourism interacts with local value systems and highlighting the unique way this occurs in slum tourism.

In the photo: Children in Kallayanpur slum, Dhaka. Photo Credit: UN Photo/Kibae Park

In the photo: Children in Kallayanpur slum, Dhaka. Photo Credit: UN Photo/Kibae Park

Above all, this is a book about tourism and one of the most interesting themes of the book is its ability to reframe tourism throughout. Academics and social activists, “professional slummers,” who visit slums are rarely criticized to the same extent as tourists but Frenzel challenges the division between slum tourist and professional slummer, suggesting that professional slummers are a type of slum tourist. While this seems like a controversial suggestion, this is part of a wider approach which views tourism as so much more than the industry of packaged holidays, compounds and resort towns: Instead, it is intended as a social practice which educates tourists and helps to increase the visibility of slums in the form of transport services, social justice projects and social capital.

In contemporary society, there has been a rise in rebellious tourism. Rebellious tourism, according to Frenzel, can be seen as a search for an authentic experience away from wage-labor, the world of work and explicit, conspicuous consumption. Slums offer this to tourists, not because of their status as areas of poverty, but because they offer a modern user-made urban landscape which revolves around communal living and space. Slums are framed as user-generated settlements which are ephemeral and versatile. There is something about the slum that cannot be defined because the slum is constantly changing. Frenzel shows that there is much more to slums than poverty, painting the slum not as an isolated place but one connected to the city through labor, leisure and tourism.

Yet the slum is framed as a site of conflict for the same reasons. Throughout the book, Frenzel explains that the plurality of the slum creates a struggle for definition, land use and recognition.

Related Article: “BOOK REVIEW: THE REFUSAL OF WORK”

Adding a social layer to tourism, Frenzel illustrates that slum tourists can be tourist researchers with benefits for the tourists and slum residents alike.

The book outlines that slum tourism is inherently linked to wider social questions such as the alleviation of poverty. Situating slumming historically, Frenzel connects the rise in slum tourism to the rising inequalities in our modern world. Through visiting slums, tourists can disrupt value regimes which stigmatize slums by making them more visible. However, he stresses that this has to be rooted in a politics of solidarity which allows for what he calls “agency” or inter-action by both slum residents and tourists.

Solidarity requires not looking at residents of slums as helpless victims in need of saviors but instead through a new kind of touristic lens which allows for the creation of dialogue and mutual exchange. Frenzel suggests that this could include building political coalitions which fight against evictions, demand public services and limit police brutality. He even suggests the creation of exchange trips where residents of slums could visit the tourist’s home country. But these need to be built around what residents want and ask for.

By anchoring discussions of slum tourism in a debate around “agency”, Frenzel exhibits a keen sensitivity to the complex power relations at play.

In the photo: The Rochina Favella Photo Credit: UN Photo/K McGlynn

In the photo: The Rochina Favella Photo Credit: UN Photo/K McGlynn

The book has many strengths and one of them is undoubtedly how Frenzel avoids turning slum residents into one homogeneous group by attempting to speak for them. The author rightfully highlights the fact that many different kinds of people live in slums for a variety of reasons; thus, among slum residents, there is a wide variety of opinions on slum tourism. However, interviews with residents of slums are largely missing from the book. How residents feel about tourists should form a big part of any conversation about slumming, and perhaps, a chapter dedicated to residents responses to tourism would have provided the reader with useful contextual information.

All in all, Frenzel has crafted a book which provides both a fresh and innovative approach to tourism generally and slum tourism specifically. Through placing emphasis on the need for slum tourism to be ethical through involving and respecting residents, he is sensitive to the power relations involved. The book is thought-provoking and manages to overturn the reader’s stereotypes regarding slums while encouraging them to be aware of their own practices as a tourist.

Recomended Reading:” GOOGLE MAPS IS ADDING OFTEN INVISIBLE FAVELAS TO THEIR CARTOGRAPHY OF RIO AHEAD OF THE OLYMPICS“